Chapter 1: Snapshot - Chinese History + the Rest of the World

Chapter Text

This is by no means comprehensive! But when I was given an introduction to Chinese history in school, it was taught in isolation, so I had no idea (1) what Gregorian calendar year major dynastic events occurred in, since China used both its own calendar system plus regnal years for individual emperors to record important events; (2) what was going on in the rest of the world.

So, this is my small attempt to put together some sort of comparison and try to fit things together. WARNING: this is a China-centric breakdown of events. Please note that during the periods of disunion, there are simply too many small states, capitals, and founding kings to list, so those have been skipped over. Also pre-historic and post-dynastic (i.e., modern) eras are excluded.

Xia 夏 c. 2070–1600 BCE

- capital: Yangcheng 陽城 (modern day Dengfeng, Henan province)

- dynastic surname: Sì 姒

- founder: Yǔ 禹

- total # emperors: 17

Significant Events in China

- stone tools

- c. 11,000-8000 BCE: domestication of rice

- 7000 BCE: millet agriculture develops

- 5500 BCE: buildings, pottery, burials, specialization

- 3630 BCE: silk garments (sericulture)

- earliest metal bells, lacquer-ware

Significant Events in the World

- ~40,000 years ago: diaspora from Africa began

- c. 11,000-6000 BCE: agriculture develops in Syria & Iran; domestication of animals begins

- c. 10,000-9000 BCE: first religious structure built in Gobekli Tepe in Turkey

- c.7000 BCE: agriculture established in Europe

- c. 5500 BCE: irrigation developed in Mesopotamia

- 5000 BCE: first plant-based (cotton) fabric in Mehrgarh, Indus Valley

- c. 4500 BCE: first city in the world -- Uruk of Mesopotamian civilization

- c. 3300 BCE: world's first writing -- Egyptian hieroglyphs

- 3150 BCE: unified Egypt

- c. 3100 BCE: Bronze Age begins in western Asia & Central Europe

- c. 2950-2500 BCE: Stonehenge built in Wiltshire, England

- 2879–258 BCE: Hồng Bàng dynasty of Vietnam

- c. 2800-1800 BCE: Norte Chico civilization of Peru

- c. 2600 BCE: pyramids at Caral, Peru

- c.2600s BCE: Minoan Civilization began

- 2600 BCE: earliest sewer systems in Indus Valley

- c.2560-2540 BCE: Great Pyramid of Giza built

- c. 2200 BCE: iron first worked in Hittite Empire

- c. 2000 BCE-1697 CE: Maya civilization of Mexico

Shang Dynasty 商 (c. 1600 - 1050 BCE)

- (eventual) capital: Yin 殷 (modern day Anyang, Henan province)

- dynastic surname: Zǐ 子

- founder: Tāng 湯

- total # emperors: 30

Significant events in China

- first historical/written records (oracle bones)

- perfected technique to create bronze vessels and early ceramics

Significant events in the world

- Gojoseon Kingdom in Korea 2333-194 BCE

- New Kingdom in Egypt 1550-1069 BCE; establishment of Valley of the Kings and Queens as burial sites

- Mycenean civilization (Greece) ~1600-1100 BCE

- Phoenician empire 1200-539 BCE

- 1200-1101 BCE: Iron Age across Eurasia

- c. 1200-400 BCE: The Olmec civilization in Mexico

Zhou Dynasty 周

Western Zhou 西周 (1050-770 BCE)

Eastern Zhou 東周 (770-150 BCE)

- capital: Haojing 鎬京 (modern day Xi'an, Shaanxi province)

- dynastic surname: Jī 姬

- founder: Fā 發 (Wǔ Wáng 武王)

- total # emperors: 38

Spring & Autumn Period 春秋 (770-479 BCE)

Warring States Period 戰國 (476-221 BCE)

Significant events in China

- Iron Age; zenith of bronze-ware making

- established semi-feudal system of government and concept of Mandate of Heaven

- government irrigation projects for crops

- Spring and Autumn Period: Hundred Schools of Thought (including Confucianism, Legalism, Mohism)

Significant events in the world

- Carthaginian Empire ~1000-146 BCE

- 900-27 BCE: Etruscan civilization

- c. 900-200 BCE: Chavin de Hantar in Andes of South America

- 776 BCE: first Olympic Games in Ancient Greece

- 753 BCE: legendary founding of Rome by Romulus

- 6th century BCE in Greece: establishment of city-states, with Athens, Sparta, Corinth & Thebes dominating

- 509-27 BCE: Republic of Rome

- c. 500 BCE-1521 CE: Zapotec in Mexico

- 400 BCE-250 CE: Yayoi period of Japan

- 323-146 BCE: Hellenistic Greece

- 332 BCE: Egypt conquered by Alexander the Great

- 332-30 BCE: Ptolemaic era of Egypt

- 321-185 BCE: Maurya Empire in India

Qin Dynasty 秦 (221-206 BCE)

- capital: Xianyang 咸陽 (near modern day Xi'an, Shaanxi province)

- dynastic surname: Yíng 嬴

- founder: Ying Zheng 嬴政 (Shi Huangdi 始皇帝)

- total # emperors: 2

Significant events in China

- first unified China, centralized government

- standardized writing, weights & measures

- blast furnaces (Terra Cotta) (new discoveries in archaeology indicates that this technique was brought into China from Greece via trade routes through the Middle East)

Significant events in the world

- Kingdom of Numidia in Tunisia 202-46 BCE

Han Dynasty 漢

Western Han 西漢 (202 BCE-9 CE)

Eastern Han 東漢 (25-220 CE)

- capitals: Chang'an 長安, Luoyang 洛陽, Xuchang 許昌 (modern day Xi'an, Shaanxi province; Luoyang and Xuchang, Henan province; respectively)

- dynastic surname: Liú 劉

- founder: Liu Bang 劉邦

- total # emperors: 30

Xin Dynasty 新 (9-23 CE)

Significant events in China

- Confucianism as official philosophy

- start of civil service examination system

- based on Qin, establish & expanded government monopolies, including salt, iron, liquor production, bronze-coin currency

- Imperial universities

- standard history texts by Sima Qian & Ban family that would influence later text dealing with dynastic cycle and histories

- Silk Road formally established

- 2 CE: first census

Significant events in the world

- India: ~200 BCE - 700 CE, Epic & Early Puranic Period; 30-375 CE, Kushan Empire

- Teotihuacan period of Mexico ~100 BCE - 700s CE

- Roman Empire (Western) 27 BCE - 476 CE

- Kingdom of Aksum in Ethiopia ~100-940 CE

- Three Kingdoms in Korea 37 BCE - 935 CE; Gaya confederacy 42-562 CE

- Vietnam: Kingdom of Nam-Viet 204–111 BCE, Kingdom of Funan 68-550 CE, Champa Kingdom 192-1832 CE

- c. 100-600 CE: Teotihuacan in Mexico

- c. 200 BCE - 1050 CE: Pyu city-states of Myanmar

- 70-80 CE: Colosseum built

- 79 CE: eruption of Vesuvius

- 180 CE: end of Pax Romana

Intermediate Period

Three Kingdoms 三國 (220–265 CE)

- Wei 魏, founded by Cao Cao 曹操

- Shu 蜀, founded by Liu Bei 劉備

- Wu 吳, founded by Sun Quan 孫權

Western Jin 西晉 (265–317 CE)

Eastern Jin 東晉 (317–420 CE)

- capitals: Luoyang 洛陽, Chang'an 長安, Jiankang 建康 (see Han dynasty for first 2 modern locations; final city is modern day Nanjing, Jiangsu province)

- dynastic surname: Sima 司馬

- founder: Sima Yan 司馬炎 (Wudi 武帝)

- total # emperors: 15

Sixteen Kingdoms 十六國 (304–439 CE)

Southern and Northern Dynasties 南北朝 (420–589 CE)

Significant events in China

- introduction of Buddhism

- drinking tea popularized in Southern & Northern Dynastic period

Significant events in the world

- Japan: Kofun period 250-538 CE, Asuka period 538-710 CE

- c. 320-543 CE: Gupta Empire in India

- 4th century CE: mariner's compass invented in India

- c. 400-1200 CE: Ghana Empire in West Africa

- 476 CE: Odoacer captures Ravenna, deposes last Roman emperor, thus ending Western Roman Empire

- 500s CE: spinning wheel/cotton gin invented in India

- 532-537 CE: Hagia Sophia built

- Kingdom of Chenia in Cambodia 550-706 CE

Sui and Tang Dynasties

Sui 隋 (581–618 CE)

- capitals: Daxing, Luoyang 洛陽 (modern day Xi'an and Luoyang)

- dynastic surname: Yang 楊

- founder: Yang Jian 楊堅 (Wendi 文帝)

- total # emperors: 5

Tang 唐 (618–907 CE)

- capital: Chang'an 長安, Luoyang 洛陽 (modern day Xi'an and Luoyang)

- dynastic surname: Lǐ 李

- founder: Li Yuan 李淵 (Gaozu 高祖)

- total # emperors: 21

Zhou 周 (690–705 CE)

- capital: Luoyang 洛陽

- dynastic surname: Wu 武

- founder: Empress Wu (AKA Wu Zetian 武則天)

- total # emperors: 1

Significant events in China

- Grand Canal built

- Sui legal code established & Tang one based on this (to later influence Ming code)

- re-establishment of civil service exams

- re-opened Silk Road, expand maritime trade

- 650 CE: Islam first introduced

- 755-763 CE: An Lushan Rebellion

Significant events in the world

- Medieval & Late Puranic Period of India 500-1500 CE

- Middle Ages in Europe

- mid-7th century CE: Arab Muslim conquest of Mesopotamia

- Eastern Roman Empire 330-1453 CE

- Sri Vijaya in Sumatra/Indonesia, 650-1377 CE

- Sunda Kingdom in Java, 669-1579 CE

- Khanem-Bornu Empire of Africa, c. 700–1380 CE

- Nara period in Japan, 710-794 CE

- 718-1285 CE: period of the Crusades in Europe

- Heian period in Japan, 794-1185 CE

- Khmer Empire in Cambodia, 802-1431 CE

- Pagan Kingdom in Myanmar, 849–1297 CE

- Later Three Kingdoms in Korea, 892-935 CE

Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms 五代十國 (907–960 CE)

Significant events in China

Significant events in the world

- Kingdom of Dali, 937-1253 CE

- Goryeo period in Korea, 918-1392 CE

- Toltecs in Mexico, 987-1187 CE

Song Dynasty and Concurrent Dynasties

Northern Song 北宋 (960–1127 CE)

Southern Song 南宋 (1127–1279 CE)

- capitals: Bianjing 汴京, Lin'an 臨安 (modern day Kaifeng, Henan province and Hangzhou, Zhejiang province)

- dynastic surname: Zhao 趙

- founder: Zhao Kuangyin 趙匡胤 (Taizu 太祖)

- total # emperors: 18

Liao 遼 (916–1125 CE)

Western Liao 西遼 (1124-1220 CE)

Jin 金 (1115–1234 CE)

Western Xia 西夏 (1038–1227 CE)

Significant events in China

- expanded rice cultivation doubled population (since Tang)

- vibrant city life: first restaurants, city night life

Significant events in the world

- Vietnam: Dai Viet period 1054-1400 CE and 1428-1804 CE

- 1055 CE: Norman Invasion of England, crowning of William the Conqueror

- Turkish Empire, c. 1055-1250s CE

- Great Zimbabwe, c. 1100-1400 CE

- Kingdom of Benin 1180–1897 CE

- 1113-1150 CE: Angkor Wat built in Cambodia

- Kamakura period in Japan, 1185-1333 CE

- 1215 CE: Magna Carta in England

- Inca Empire in Peru, early 1200s-1572 CE

- Kingdom of Sukhothai in Thailand 1238-1583 CE

Yuan Dynasty 元 (1271–1368 CE)

- capital: Khanbaliq 汗八里 or Dadu 大都 (modern day Beijing, Hebei province)

- dynastic surname: Borjigin ᠪᠣᠷᠵᠢᠭᠢᠨ 孛兒只斤

- founder: Borjigin Temüjin 孛兒只斤鐵木真 (AKA Genghis Khan)

- total # emperors: 16 (and 3 in Northern Yuan, post-Ming takeover)

Significant events in China

- 1270s: Marco Polo visits China

- cloisonné introduced

Significant events in the world

- Mali Empire in West Africa c. 1230–1670 CE

- 1241 CE: Mogol invasion of Europe

- Majapahit Empire on Java 1293-1527 CE (ruled Indonesian archipelago & Malay Peninsula etc)

- Ottoman Empire 1299-1922 CE

- Aztec Empire 1325-1521 CE

- Japan: Kenmu Restoration 1331-1338 CE, Muromachi period 1337-1573 CE

- Europe: start of the Renaissance in ~mid-14th century in Florence, Italy

- 1346-1353 CE: Black Plague in Europe

- Kingdom of Ayutthaya in Thailand 1351-1767 CE

Ming Dynasty 明 (1368–1644 CE)

- capitals: Yingtian Prefecture 應天府, Shuntian Prefecture 順天府 or Jingshi 京師 (modern day Nanjing and Beijing)

- dynastic surname: Zhū 朱

- founder: Zhu Yuangzhang 朱元璋 (Gaodi 高帝)

- total # emperors: 16 (and 6 in Southern Ming, post-Qing takeover)

Significant events in China

- Great Wall rebuilt into current form

- 1403 CE: Yongle Emperor moves capital from Nanjing to Beijing

- 1405-1433 CE: Zheng He's treasure voyages

- 1406-1420 CE: Forbidden City built

Significant events in the world

- Kingdom of Kongo 1390–1914 CE

- Joseon period of Korea 1392-1897 CE

- The Malacca Sultanate (Malay Peninsula etc) 1400-1511 CE

- Aztec Empire in Mexico, 1428-1521 CE

- Inca Empire in Andes, South America 1438–1533 CE

- 1450 CE: Gutenberg's printing press

- 1450s CE: Machu Picchu constructed

- 1453 CE: fall of Constantinople (and Eastern Roman Empire) to Ottoman Turks

- c. 1464–1591 CE: Songhai Empire of Western Africa

- 1469 CE: marriage of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile leads to unification of Spain

- 1512 CE: Portuguese arrive in Indonesian archipelago

- Mughal Empire in India 1526-1857 CE

- 1582 CE: Pope Gregory XIII issues Gregorian calendar (last day of Julian calendar Thursday, 4 October 1582; first day of Gregorian calendar Friday, 15 October 1582)

- 1602 CE: Dutch East India Company established

- 1632–53 CE: building of Taj Mahal

- Japan: Sengoku period 1467-1573 CE, Azuchi-Momoyama period 1569-1603 CE, Edo period 1603-1868 CE

Qing Dynasty 清 (1636–1911 CE)

- capital: Beijing 北京

- dynastic surname: Aisin Gioro ᠠᡳᠰᡳᠨ ᡤᡳᠣᡵᠣ 愛新覺羅

- founder: Nurhaci 努爾哈赤

- total # emperors: 12

Significant events in China

- 1840 and 1842 CE: Opium Wars

- 1851-1864 CE: Taiping Rebellion

- 1899-1900 CE: Boxer Rebellion & Eight-Nation Alliance

- borders extended into Inner Mongolia and Manchuria to the north

- sent naval expeditions to the south, the indigenous Baiyue of modern-day Guangdong and northern Vietnam (the latter called Jiaozhi, and then Annam during the Tang dynasty) were also quelled and brought under Chinese rule

Significant events in the world

- 1721–1917 CE: Russian Empire

- 1816–1897 CE: Zulu Kingdom in South Africa

- 1821 CE: Greece declare independence from Ottoman Empire, although not fully achieved until 1829 CE

- 1838 CE: Pitcairn Islands in South Pacific the first to grant women's suffrage (right to vote in elections)

- Europe: Age of Enlightenment estab mid-1600s, Industrial Revolution 1760-1840 CE, French Revolution 1789-1799 CE, Napoleonic Wars 1803-1815 CE, Revolutions of 1848

- American Revolution 1775-1783 CE, Declaration of Independence 1776 CE

- Korean Empire 1897-1910, then Japanese rule of Korea 1910-1945 CE

- Empire of Japan 1868-1945 CE

- 1883 CE: Krakatoa volcano explosion

- 1859 CE: Darwin's On the Origin of Species published

Chapter 2: Snapshot - Chinese Written Language

Chapter Text

Chinese writing is like the ancient Egyptian one: hieroglyphic/pictographic. Each character represents a word; very often, a pair of characters can also represent a word/concept. Each character is also monosyllabic.

Chinese characters are divided into two major parts:

(1) radical (部首 "bùshǒu") - this groups characters into categories related to meaning; consider it the root of the word

(2) rebus - this gives the phonetic/inflection part of the word; however, because Chinese is not alphabetic and is tonal, this second part is not a simple or accurate guide to how exactly to pronounce the entire word; plus the pronunciation of many words has changed over the centuries

Because Chinese characters are essentially glyphs, they are put together like a jigsaw puzzle, with each component made up of different strokes.

For example,

晚 "wǎn" (evening/night)

has a total of 11 strokes. 4 strokes for its radical 日 "rì" (sun, day) and 7 for its rebus.

When using a Chinese dictionary, you'll find it arranged by radicals and by number of strokes. Characters are grouped together by radical. Radicals are arranged in numeric order (total number of strokes per radical). To find a particular character, you need to first look up the radical and then the rebus by its number of strokes (i.e., you don't look up the total strokes for the character but in its two parts: total strokes for radical + total strokes for rebus).

So, for "wan", you find it under the 4-strokes radical 日, and then in the 7-strokes section of that radical.

Stroke Order

Like all writing systems, there are some basic rules for writing Chinese characters:

(1) from top to bottom

(2) from left to right

There are more rules than that, of course, but let's not get bogged down with too many. (NOTE: you may read Chinese from top to bottom and right to left in traditional books, but you write individual characters from left to right. It's a balance thing. ;))

These are the basic forms:

(1) dot (點 "diǎn")

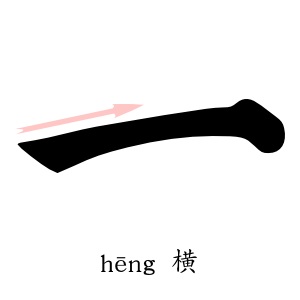

(2) horizontal (横 "héng")

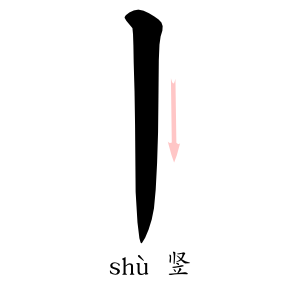

(3) vertical (豎 "shù")

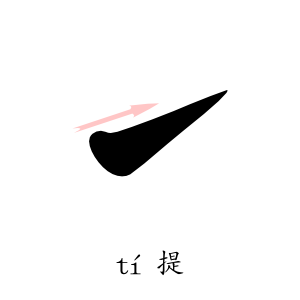

(4) rise (提 "tí")

(5) press down (捺 "nà")

(6) throw away (撇 "piē")

(7) hook (鉤 "gōu")

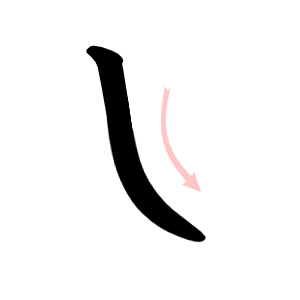

(8) bend (彎 "wān")

(9) slant (斜 "xié")

(10) break (折 "zhé") - which indicates a change in stroke direction, usually 90° turn, going down or going right only—as opposed to a variety of stroke

So, you combine these basic strokes together to form chinese characters.

Tonality

As I’ve mentioned in my guide to family trees, Chinese is a tonal language. What that means is that for every character/word in the Chinese lexicon, there is more than one way of pronouncing it, and the different pronunciation/inflection is related to a different meaning/usage of that word. This is one of the reasons why there are so many jokes (and sometimes vicious taunting) related to mispronunciation resulting in a word, a phrase, or a sentence meaning something else simply because the tonality is off.

So, when you say a particular word, you can't just say the mixture of consonant and vowel sounds any which way; you have to have the right pitch (high, low, rising, falling, etc.) as well. Think of it like singing a note—you can't just sing any note of C and expect people to know you mean middle-C. Sing middle-C.

Mandarin has up to 5 tones per character/word. Cantonese has up to 9. (I say "up to" because not all tones denote a different meaning for each character—some only have 3 tones for 3 meanings/usages.)

For Mandarin, the 5 tones are as follows (using the letter “e” with markings to demonstrate):

1st tone = ē — high pitched and level tone

2nd tone = é — rising pitch

3rd tone = ĕ — dips then rises

4th tone = è — high then descends

Neutral = e — short and undefined pitch

Some examples of how tonality affects meaning for the same character:

樂 lè = happy, yuè = music, yào = enjoyable, lào = placename in Hebei province

覺 jué = aware, jiào = sleep

These are the more extreme examples of commonly-used words whose tonalities differ greatly depending on context. With others, it's more a slight variation of tonality/pitch that separates the different meanings/usages.

Homophones

Because the human mouth and tongue can only be shaped in so many ways to produce sounds that become words and because certain cultures prefer certain sounds over all available ones, there is a set limit in Chinese as in any other language. This means that homophones (words that sound identical but with completely different meanings) exist. As confusing as this already is, there is an added layer of confusion when rendering Chinese into its transliterated forms (i.e., pinyin or the older version known as Wade-Giles). Without adding the numbers/symbols to denote tonality, many more pinyin words end up being shared by Chinese characters that, in the original language, are not homophones at all—or at least, not so identical in sound.

Chapter 3: Snapshot - Chinese Grammar

Chapter Text

Unlike many languages, Chinese grammar is very straight-forward, you'll be glad to know—sort of makes up for the difficulty of the non-alphabetical vocab combined with tonality! There're no verbal conjugations and sentence structure follows a simple pattern (unlike, for example, Latin, where not only do subjects and verbs have to be modified but the order in which subjects, verbs, and objects appear in a sentence doesn't matter!).

Sentences in chinese follow this basic principle: subject + verb + object

Here are some examples:

我愛他 (wǒ ài tā) - I love him

你要睡覺 (nǐ yào shuìjiào) - You need (to go to) sleep

他們喝酒 (tāmén hē jiǔ) - They are drinking wine

You'll notice in sentence 2 that the verb 要 (yào) encompasses the full expression of "need to do something". One thing you'll note about Chinese is that it is minimalist—if you can say it in three words instead of nine, you do it. And the term for sleep in sentence 2 is a compound term.

Now, sentence 3 shows how to create plural subjects: by adding 們 (mén) after the singular subject.

Here are the various subject words:

我 (wǒ) = I

你 (nǐ) = you

他 (tā) = he/she (she can also be written as 她)

我們 (wǒmén) = we

你們 (nǐmén) = you guys ("vous" in French; for whatever reason, this term got dropped into the English channel during the Norman invasion...

or something)

他們 (tāmén) = they

Pronouns are created by adding the possessive 的 (dī or de):

我的 (wǒ de) = my

你的 (nǐ de) = your

他的 (tā de) = his/her(s) (again, her can also be written as 她)

我們的 (wǒmén de) = our

你們的 (nǐmén de) = your

他們的 (tāmén de) = their

Of course, the basic S-V-O structure is hardly sufficient to express every possible thought, emotion, idea, argument people are capable of. So, you build on this basic structure by adding modifiers (adjectives and adverbs), classifiers (quantities and measures), locators (time and place), negations, questions, indirect objects, and all the rest.

Here are some common types of sentences you'll come across and how to formulate them. Remember, you do not need to conjugate so that subjects and verbs correlate.

1. Indirect object: subject + verb + indirect object + direct object

他給我禮物 (tā gěi wǒ lǐwù) - He gives me (a) gift

For the most part, when the object (indirect or direct) is a person, the same word is used as in the case where the person is the subject, namely:

我 (wǒ) = me

你 (nǐ) = you

他 (tā) = him/her (again, her can also be written as 她)

我們 (wǒmén) = us

你們 (nǐmén) = you guys

他們 (tāmén) = them

2. Time: subject + time + verb + object (time + subject + verb + object is also acceptable)

Because there are no conjugations in Chinese, verb tenses are denoted by a "time" word(s).

我昨天到了動物園 (wǒ zuótiān dàole dòngwùyuán) - Yesterday, I went to the zoo

我今天到了動物園 (wǒ jīntiān dàole dòngwùyuán) - Today, I'm going to the zoo

我明天會到動物園 (wǒ míngtiān huìdào dòngwùyuán) - Tomorrow, I'll go to the zoo

As you can see, the subject, verb, and object do not change whatsoever, but the addition of a time indicator tells you when something happens. 了 (le or liǎo) and 會 (huì) are indicators that I won't get into right now. The important terms to remember here are the time words:

昨天 (zuótiān) = yesterday

今天 (jīntiān) = today

明天 (míngtiān) = tomorrow

3. Negation: subject + negation term + verb + object

我不喜歡他 (wǒ bù xǐhuān tā) - I don't like him

我没有問題 (wǒ méiyǒu wèntí) - I don't have a problem or I don't have any questions

我不要吃鵝肝 (wǒ bùyào chī égān) - I don't want to eat foie gras

不 (bù) is almost always the negation term used, but there are some others. 没有 (méiyǒu) are usually paired when you mean that you have no need of something or are missing something. The 不要 (bùyào) combo is only used when you don't want to do something.

4a. Question: subject + verb + object + question term

你吃了飯嗎? (nǐ chīle fàn ma) - Have you eaten yet?

我們出去吃飯吧. (wǒmen chūqù chī fàn ba) - Shall we go out and eat? (or Let's eat out!)

我過得很好,你呢? (wǒ guòdé hěnhǎo, nǐ ne) - I'm fine; how about you?

The above are examples of the most common question terms, and they aren't easily interchanged without changing the context of the question.

嗎 (ma) - the most common question term and used for basic yes/no questions

吧 (ba) - is a suggestive question term (i.e., do you think it's a good idea if...) and usually doesn't have a question mark at the end of the sentence

呢 (ne) - for more open-ended questions

4b. Affirmative-negative question: subject + verb + negative verb form + object

你是不是中國人? (nǐ shì-bù-shì zhōngguórén) - Are you Chinese?

你要不要咖啡? (nǐ yào-bù-yào kāfēi) - Do you want coffee?

他們來不來? (tāmen lái-bù-lái) - Are they coming?

This type of question always involves duplicating the verb and putting 不 (bù) in between to make up the affirmative and negative forms.

4c. Why: subject + why + verb + object (why + subject + verb + object is also acceptable)

你為什麼不吃飯? (nǐ wèishénme bù chīfàn) - Why won't you eat your dinner?

In this case, the verb is actually in the negative form.

5. Location/Position: subject + 在 + location

他在美國 (tā zài měiguó) - He's in the States

他在這兒 (tā zài zhè’ér) - He's over here

他在那邊 (tā zài nàbiān) - He's over there

Note that there's no need for the verb "to be" for this type of sentence; it's implicit with the use of 在 (zài).

6. Adjectives/Adverbs: generally, the modifier/quantifier precedes the noun/verb

黑馬奔跑得快 (hēimǎ bēnpǎodé kuài) - the black horse gallops quickly

這個冬天很冷 (zhègè dōngtiān hěn lěng) - it's very cold this winter

The structure of sentences containing adjectives and adverbs are less straight-forward in terms of having one overall formula, so I'm not providing one at this time. I've managed to provide two examples using the S-V-O format, but, really, once you get into sentences with descriptors like adjectives, adverbs, clauses, and quantifiers, you tend to want to express a more sophisticated thought, so the basic S-V-O structure doesn't usually cover it.

7. Imperative (Command): verb (+ ending expression)

走吧! (zǒu ba) - Let's go!

請! (qǐng) - an expression of invitation (Please!)

來來來! (lái-lái-lái) - another expression of invitation (Come join us!)

Pretty much like French, just without the conjugations. ;) 吧 (ba) is the most common ending expression.

Chapter 4: Snapshot - Common Classifier Words 量詞

Chapter Text

In English, there are articles like "the" and "a(n)". The Latin languages make it more complex by dividing things into male and female. But the Chinese system is, I think, the worst when it comes to categorizing and qualifying objects.

Classifier words are placed in front of (usually) nouns to label them. They are usually a combination of quality and measure. They can be subdivided into categories related to measures and weights, time, money, and so on. And woe to those who pair the wrong classifier with the wrong object—clearly not a native speaker and/or certainly uneducated/uncouth.

So, here's a list of some of the more common classifiers, along with their main usages, you'll come across in everyday Chinese:

quantity (1, 2, 3...) + 個 gè - individual things, people; the most commonly used classifier (if you're stuck not knowing the right term, use this as the default)

EXAMPLE: 三個人 = three people/persons

quantity (1, 2, 3...) + 隻 zhī - animals; body parts; miscellaneous

EXAMPLE: 兩隻鳥 = a pair of birds, i.e. two birds

quantity (1, 2, 3...) + 條 tiáo - long, skinny objects

EXAMPLE: 九條龍 = nine dragons

quantity (1, 2, 3...) + 件 jiàn - items that come in (large) pieces, clothes; matters

EXAMPLE: 七件行李 = seven pieces of luggage; 三件事 = three affairs/situations/things to do

quantity (1, 2, 3...) + 片 piàn - slices of things

EXAMPLE: 五片菠蘿 = five slices of pineapple

quantity (1, 2, 3...) + 粒 lì - grains, pellets of things

EXAMPLE: 十粒豆 = ten beans

quantity (1, 2, 3...) + 塊 kuài - pieces of (small) things; money

EXAMPLE: 四塊麵包 = four slices of bread, 十塊錢 = ten dollars

quantity (1, 2, 3...) + 杯 bēi - cup of things

EXAMPLE: 六杯茶 = six cups of tea

quantity (1, 2, 3...) + 碗 wǎn - bowl of things

EXAMPLE: 四碗湯 = four bowls of soup

quantity (1, 2, 3...) + 盒 hé - box of things

EXAMPLE: 一盒飯 = a box of cooked rice (often connoting other food items contained within)

quantity (1, 2, 3...) + 包 bāo - package/bundle of things

EXAMPLE: 一包餅乾 = a pack of cookies

quantity (1, 2, 3...) + 雙 shuāng - pair of things

EXAMPLE: 一雙筷子 = a pair of chopsticks

quantity (1, 2, 3...) + 對 duì - matched pair of things

EXAMPLE: 一對鴛鴦 = a matched pair of mandarin ducks, a pair of lovers

quantity (1, 2, 3...) + 支 zhī - (also written 枝) stick-like objects

EXAMPLE: 四支筆 = four pens

quantity (1, 2, 3...) + 張 zhāng - objects with flat surfaces

EXAMPLE: 一張唱片 = a record/an album (of music)

quantity (1, 2, 3...) + 本 běn - volume of bound print matter

EXAMPLE: 一本雜誌 = a magazine

quantity (1, 2, 3...) + 間 jiān - rooms, spaces

EXAMPLE: 兩間屋子 = two houses

quantity (1, 2, 3...) + 打 dá - dozen

EXAMPLE: 一打蛋 = a dozen eggs

the following are used as is, without quantifiers:

一些 xiē - (plural) some unspecified quantity of things

EXAMPLE: 一些禮物 = a bunch/pile of gifts

一群 qún - a group of, a herd of

EXAMPLE: 一群青年 = a group of youths

Chapter 5: Snapshot - Reduplication 疊詞 “dieci”

Chapter Text

Some of you may have noticed something that's pretty unique to the Chinese language: the use of repetition of single words in a sentence, poem, or lyric.

The technical term for this pattern of repetition is 疊詞 diécí, known as "reduplication" in English (even though the technique doesn't exist in English poetry or prose). There’s another similar term 疊字 “diézì”, which relates to the repetition of a character or radical to form a new word, that some have made synonymous with 疊詞 diécí, but they are not the same thing.

The purpose of 疊詞 diécí is mostly as a stylistic construct, to add emphasis or subtle complexities to meaning and tone. There are two major types: verb and adjective, and their uses determine the pattern/format of the 疊詞 diécí within the sentence.

Here are some examples:

1. ABB

a. for verb reduplication, usually brief actions and often with a touch of the imperative (command)

你看看。(nǐ kànkàn) - have a look

去走走吧!(qù zǒuzǒu ba) - (let's) go out for a bit

b. for adjective reduplication

甜絲絲 (tián sīsī) - sweetly

笑哈哈 (xiào hāhā) - laughingly

血淋淋 (xuè línlín) - bloodily

冷冰冰 (lěng bīngbīng) - coldly

2. AAB - for adjective reduplication, used in conjunction with the term 的 "de" (of)

果汁甜甜的。(guǒzhī tiántián de) - the juice is sweet

我女朋友的眼睛大大的。(wǒ nǚpéngyǒu de yǎnjīng dàdà de) - my girlfriend has big eyes

3. ABA - for verb reduplication, used in conjunction with the term 一 “yī” (one)

笑一笑!(xiào-yī-xiào) - smile!

你去問一問他。(nǐ qù wèn-yī-wèn tā) - go ask him

4. AABB - for compound adjective reduplication

高高興興 (gāogāo xìngxìng) - happily, excitely

舒舒服服 (shūshū fúfú) - comfortably

辛辛苦苦 (xīnxīn kǔkǔ) - with much suffering and effort

清清楚楚 (qīngqīng chǔchǔ) - (comprehensively) clear

客客氣氣 (kèkè qìqì) - politely

迷迷糊糊 (mímí húhú) - with confusion

5. ABAB - for compound verb reduplication

考慮考慮 (kǎolǜ kǎolǜ) - to deliberate carefully

商量商量 (shāngliàng shāngliàng) - to discuss rationally

Chapter 6: Snapshot - Bagua 八卦

Chapter Text

In the Daoist (Taoist) cosmological layout of the universe, everything is composed of the 陰 yīn and 陽 yáng opposing dualities as well as the five elements of metal, wood, water, fire, and earth.

The nature of 陰 yīn is considered feminine, passive, receptive, and retractive while 陽 yáng is masculine, active, repelling, and expansive. The interconnectedness and interdependence of 陰陽 yīn-yáng is symbolized by the well-known 太極 tàijí diagram (see central circular object in the bagua diagram below). There were no negative or evil associations with 陰 yīn, just later patriarchal bias toward things that are not 陽 yáng.

Daoist philosophy also believes in the fundamental trinity of the heavens (sky), the earth, and humans as the bridge between the heavens and the earth. This trinity is expressed as 天地人tiān-dì-rén.

As the Daoists sought to further organize the universe, they felt that all matter was formed from eight greatest phenomena of the nature: sky, earth, fire, water, mountains, oceans, wind, and thunder. They arranged these eight phenomena into the octagonal 八卦 bāguà structure (bāguà means “eight areas”), assigning a name, a direction, an element, and a number to each.

The 八卦 bāguà plan always has South on top and the other seven spots are arranged according to the eight directional points.

In the first arrangement of the 八卦 bāguà, later known as the Early Heaven Bagua, polar opposite yin-yang pairs of phenomena were set so that they represented the ideal worldview. Thus Heaven (乾 qián) above, and associated with warm yang energy, was placed on top in the southerly position; its opposite Earth (坤 kūn) was in the northerly position at the bottom. Fire (離 lí), associated with the sun, was in the east (sunrise) and Water (坎 kǎn), associated with the moon, was in the west (moonrise). The remaining four phenomena were arranged to correspond to the geographical layout of China: Mountain (艮 gèn) in the northwest (Tianshan mountains), Swamp (兌 duì) in the southeast (East China Sea), Thunder (震 zhèn) in the northeast, and finally Wind (巽 xùn) in the southwest (because apparently it’s very windy in the southwest).

Each 卦 guà is arranged as a trigram composed of either unbroken 陽 yáng lines or broken 陰 yīn ones. The 卦 guà are in a trigram format to represent the trinity of 天地人tiān-dì-rén.

Numerologically, the Early Heaven Bagua’s opposing pairs have their associated numbers sum to 9. Even though the centre of the 八卦 bāguà does not contain a specific 卦 guà, it is still assigned the number 5 and is associated with the earth element and the colour yellow.

Early Heaven Bagua 先天八卦 “xiāntiān bāguà”

Just a note on how the diagram is laid out:

- the central circular object is the 太極 tàijí symbol

- each side of the octagon illustrates the trigram for the individual 卦 guà

- the text is arranged in this order:

- Chinese name of the 卦 guà (with the natural phenomenon in brackets)

- pinyin of the Chinese terms

- English name of the 卦 guà

- directional position

- the element the 卦 guà is associated with

- the basic characteristics of the 卦 guà

- the number assigned to the 卦 guà

- the colour of the text also corresponds to the assignment to each of the cardinal positions plus the centre; the other remaining directional positions aren’t associated with a colour, so the text is in grey

But as Daoist principles became used in everyday life, whether for the natural sciences or divination, the Chinese, especially those during the Zhou dynasty, rearranged the 八卦 bāguà to be an instrument that could predict change. And so, the Late Heaven Bagua was created and the 卦 guà placed in new positions. The justification for each placement was each 卦 guà’s characteristics corresponding to particular seasons and seasonal changes. Thunder (震 zhèn) is tied to rain and therefore Spring, and thus it was assigned to the East cardinal position; the other 卦 guà fell in line accordingly to fill the remaining seven spots.

Numerologically, the opposing pairs of 卦 guà, while not polar opposites, had their sums total 10.

Late Heaven Bagua 後天八卦 “hòutiān bāguà” (AKA 伏羲八卦 “Fúxī bāguà”)

Like the Early Heaven Bagua diagram, the colour-coding and order of information is the same; just the individual 卦 guà are placed in a different position.

The 八卦 bāguà were further paired up to form hexigrams, and these hexigrams were also given names and characteristics. The hexigrams, sixty-four in total, form the basis of the I Ching (易經 yìjīng), the Book of Changes, written as a divination manual in the Western Zhou dynasty.

And the Late Heaven Bagua is still being used in Feng Shui.

NOTE: The Chinese are very East-West oriented (vs North-South). One of the major reasons is that this relates to sunrise and sunset; another is that the two major rivers, the Yellow and the Yangtze, flow from West to East. Therefore, when they list the four cardinal points, they start with East and go clockwise to North. As a result, NE, NW, SE, SW are actually named EN, WN, ES, and WS in Chinese.

Chapter 7: Snapshot - Numbers

Chapter Text

So, the following are just lists of the significance of certain numbers for the Chinese in terms of philosophy and culture (rather than math and fortune-telling); I chose just the most popular/interesting ones (i.e., just a sampling):

一 (yī) = 1

- Archaic/alternate forms: 弌,壹

- There are so many four-word idioms starting with the number one that this entry would get way too long and your eyes would go crossed were I to list them all

二 (èr) = 2

- Archaic/alternate forms: 弍,貳

- Related terms: 兩 (liǎng) “twice/both”,雙 (shuāng) “double/pair”

- 兩極 (liǎng jí) “two extremes” = 天地 (tiān dì) “heaven and earth”

- 兩儀 (liǎng yí) “two polarities” = 陰陽 “yīn and yáng” (see Ch 6: Bagua for more details); the term can also be used to mean 天地 (tiān dì) “heaven and earth”

三 (sān) = 3

- Archaic/alternate forms: 弎,參/叁

- 三才 (sān cái) “three talents” = 天地人 (tiān dì rén) “heaven, earth, and humans”, Daoist concept of how humans are the bridge between heaven and earth and form a trinity

- 三仙 (sān xiān) “three immortals” = 福祿壽 (fú lù shòu), mythical beings overseeing wealth, accomplishments, and longevity, respectively

- 三字經 (sān zì jīng) “three character classic” = a grade school primer, most likely written during the Song dynasty, that teaches basic concepts of Confucian morality

四 (sì) = 4

- Archaic/alternate forms: 𦉭,亖,肆

- Homophone: 死 (sǐ) “die, death” - although not an exact match in tonality, the similarity has caused superstition against the number and certain regions consider it unlucky

- 四季 (sìjì) “four seasons” = 春 (chūn) Spring、夏 (xià) Summer、秋 (qiū) Autumn、冬 (dōng) Winter

- 四合院 (sì hé yuàn) = traditional style of home that uses the four cardinal points to anchor the quadrangle layout

- 四大發明 (sì dà fāmíng) “four great inventions” = 造紙術 (zào zhǐ shù) “paper-making”、指南針 (zhǐ nán zhēn) “compass”、火藥 (huǒ yào) “gunpowder”、印刷術 (yìn shuā shù) “printing”

- 文房四寶 (wén fáng sì bǎo) “four treasures of the study” = 筆 (bǐ) “brush”、墨 (mò) “ink”、紙 (zhǐ) “paper”、硯 (yàn) “ink stone”, the four most important tools in a scholar’s study for writing calligraphy (a sign of a learned man)

- 天之四靈 (tiān zhī sì líng) “four heavenly spirits” (AKA 四大聖獸 (sì dà shèng shòu) “four great sacred beasts”) = 青龍 (qīnglóng) “azure dragon”、白虎 (báihǔ) “white tiger”、朱雀 (zhūquè) “vermilion bird” 、玄武 (xuánwǔ) “black tortoise”, guardians of the four cardinal directions, east, west, south, and north, respectively

- 四大天王 (sì dà tiān wáng) “four heavenly kings” = the four Buddhist gods/devas that are guardians of the four cardinal points, 東方持國天王 (dōngfāng chí guó tiānwáng) Dhṛtarāṣṭra (east), 南方增長天王 (nánfāng zēng zhǎng tiānwáng) Virūḍhaka (south), 西方廣目天王 (xīfāng guǎng mù tiānwáng) Virūpākṣa (west), 北方多聞天王 (běifāng duō wén tiānwáng) Vaiśravaṇa (north)

- 四大美人 (sì dà měirén) “four great beauties” = considered the four most beautiful (and tragic) women in ancient China, namely 西施 (春秋) Xī Shī (Chūnqiū “Spring & Autumn period”)、王昭君 (西漢) Wáng Zhāojūn (Xīhàn “Western Han period”)、貂蟬 (東漢) Diāo Chán (Dōnghàn “Eastern Han period” (or Three Kingdoms, depending on source)、楊玉環 (楊貴妃,唐) Yáng Yùhuán (AKA Yáng-guìfēi, Tang dynasty imperial consort)

- 四書五經 (sì shū wǔ jīng) “four books and five classics” = important Confucian texts;

- (the 4)《論語》(lùnyǔ) “Analects”、《孟子》(mèngzi) “Mencius”、《大學》(dàxué) “The Great Learning”、《中庸》(zhōngyōng) “Doctrine of the Mean”;

- (the 5)《詩經》(shījīng) “Classic of Poetry/Book of Odes”、《尚書》(shàngshū) “Book of Documents”、《禮記》(lǐjì) “Book of Rites”、《周易》(zhōuyì) “I Ching/Book of Changes”、《春秋》(chūnqiū) “Spring and Autumn Annals”

五 (wǔ) = 5

- Archaic/alternate forms: 伍

- 五行 (wǔxíng) “the five elements” = 金 (jīn) “metal”、木 (mù) “wood”、水 (shuǐ) “water”、火 (huǒ) “fire”、土 (tǔ) “earth”, the basic components of all materials in the universe, according to Daoist philosophy

- 天官五獸 (tiān guān wǔ shòu) “five celestial beasts” = 天之四靈 (tiān zhī sì líng) “four heavenly spirits” (see above) plus 黃龍 (huánglóng) “yellow dragon” to represent the centre and allow for correspondence with 五行 (wǔxíng) “the five elements” (see above)

- 五嶽 (wǔ yuè) “five mountains” = 恆山 Héng Shān (north)、衡山 Héng Shān (south)、華山 Huá Shān (west)、泰山 Tài Shān (east)、嵩山 Sōng Shān (central)

- 五臟六腑 (wǔ zàng liù fǔ) “the major organs of the body” = the most important organs in Traditional Chinese Medicine

- (the 5 solid yin organs) 心 (xīn) “heart”、肝 (gān) “liver”、脾 (pí) “spleen”、肺 (fèi) “lung”、腎 (shèn) “kidney”;

- (the 6 hollow yang organs) 膽 (dǎn) “gallbladder”、小腸 (xiǎocháng)、胃 (wèi) “stomach”、大腸 (dàcháng) “large intestine)、膀胱 (bǎngguāng) “bladder”、三焦 (sān jiāo) “triple burner” (upper, middle, and lower burners; has no equivalent in Western medicine)

六 (liù) = 6

- Archaic/alternate forms: 陸

- 三書六禮 (sān shū liù lǐ) “three letters and six etiquettes” = formal marriage rituals established since the Warring States period, namely 奈採 (nài cǎi) Proposing, 問名 (wèn míng) Birthday Matching, 納吉 (nà jí, AKA 過文定 guò wén dìng) Presenting Betrothal Gifts + 聘書 (pìn shū) Betrothal Letter, 納徵 (nà zhēng, AKA 過大禮 guò dà lǐ) Presenting Wedding Gifts + 禮書 (lǐ shū) Gift Letter, 請期 (qǐng qī) Choosing the Wedding Date, 親迎 (qīn yíng) Wedding Ceremony + 迎書 (yíng shū) Wedding Letter

七 (qī) = 7

- Archaic/alternate forms: 柒

- Homophone: 齊 (qí) “even, uniform” - not the exact tonality, but similar enough, so considered a lucky number for relationships

- 七情六慾 (qī qíng liù yù) “seven emotions and six desires” = according to Buddhist philosophy,

- (the seven) 喜 (xǐ) “joy”、怒 (nù) “anger”、憂 (yōu) “sadness”、懼 (jù) “horror”、愛 (ài) “love”、憎 (zēng) “hate”、欲 (yù) “desire”;

- (the six) 色慾 (sèyù) physical body、形貌欲 (xíng mào yù) appearance、威儀姿態欲 (wēiyí zītài yù) comportment、言語聲音欲 (yányǔ shēngyīn yù) voice、細滑欲 (xì huá yù) delicateness or smoothness [of skin]、人相欲 (rén xiāng yù) physical features

- 七夕 (qī xī, AKA 七姐誕 qī jiě dàn) “Qixi Festival” = festival celebrated on the seventh day of the seventh month in honour of the mythical tragic love story of 織女 Zhinü and 牛郎 Niulang as a means of explaining the existence of the Milky Way and the two brightest stars (Altair and Vega) on opposite ends of it

- 做七 (zuòqī, AKA 七七四十九 (qī-qī-sìshíjiǔ)) “performing the seven” = Daoist mourning ritual where, using date of death as day 1, family are to perform filial obeisances every 7 days for seven cycles (i.e., a total of 49 days, which adds up to almost 1 year of mourning); because this is considered an act of 大孝 (dàxiào) “great filial piety”, the full observances need to be made towards great-grandparents, grandparents, parents, and spouses; the extended family only need to observe part of the mourning ritual (NOTE: the mourning period, per the original Confucian strictures, was 3 years for 大孝 (dàxiào), but it was later reduced to the ~49 weeks)

八 (bā) = 8

- Archaic/alternate forms: 捌

- Homophone: 發 (Cantonese: faat3) “to prosper” - the least similar in pronunciation, but the link was made and the number considered lucky; this idea spread to most of the rest of China

- 八卦 (bāguà) “the eight areas” - see Ch 6: Bagua

- 八字 (bāzì) “eight characters” = the eight aspects present at one’s birth, 「年干 (niángàn),年支 (niánzhī)」”yearly stem and branch”、「月干 (yuègàn),月支 (yuèzhī)」”monthly stem and branch”、「日干 (rìgàn),日支 (rìzhī)」”daily stem and branch”、「時干 (shígàn),時支 (shízhī)」 “hourly stem and branch”

- 八仙 (bā xiān) “eight immortals” = mythical beings in folklore, 何仙姑 He Xiangu, 曹國舅 Cao Guojiu, 李鐵拐 Li Tieguai, 藍采和 Lan Caihe, 呂洞賓 Lü Dongbin, 韓湘子 Han Xiangzi, 張果老 Zhang Guolao, 鍾離權 Zhong Liquan

九 (jiǔ) = 9

- Archaic/alternate forms: 玖

- Homophone: 久 (jiǔ) “long-lasting” - an actual tonal match, considered lucky for relationships

- 九族 (jiǔzú) “nine tribes” = one’s entire family clan (see All in the Wangxian Family, Ch 28 for more details)

- 九五至尊 (jiǔ wǔ zhìzūn) “ruler of the nine and the five” = phrase to mean the power of the emperor, as nine is the largest yang energy number and five occupies the central position in the middle of the four cardinal directions, taken from the I Ching《九五,飛龍在天》(jiǔ-wǔ,fēilóng zài tiān) “nine and five, soaring dragon in the heavens”

- 龍生九子 (lóng shēng jiǔ zi) “dragon’s nine sons” = mythical offspring of the dragon king, usually used as ornamentation for various architectural structures

- 囚牛 (qiúniú), dragon, likes music so used to adorn musical instruments

- 睚眦 (yázì), hybrid of dhole (canine) and dragon, likes to fight, adorns cross-guards on swords

- 嘲風 (cháofēng), hybrid of phoenix and dragon, likes adventures, adorns the four corners of roofs

- 蒲牢 (púláo), small, four-legged dragon, likes to roar, adorns the tops of bells and used as handles

- 狻猊 (suānní), hybrid of lion and dragon, likes sitting, adorns the bases of Buddhist idols, mirrors, incense burners, imperial rooftops

- 贔屭 (bìxì, AKA 霸下 bàxià), hybrid of turtle and dragon, able to carry heavy objects, used as decorative plinth for commemorative steles and tablets as well as bases of bridges and archways

- 狴犴 (bì'àn), hybrid of tiger and dragon, likes litigation, has strong sense of justice, adorns prison gates (to keep guard)

- 負屭 (fùxì), dragon, cultured and likes literature, adorns the tops of gravestones

- 螭吻 (chīwěn), hybrid of fish and dragon, likes swallowing, adorn both ends of the ridgepoles of roofs (to swallow all evil influences and prevent fires)

十 (shí) = 10

- Archaic/alternate forms: 拾

- 天干地支 (tiāngàn dìzhī, AKA 十干十二支 shígàn shíèrzhī) “(10) heavenly stem and (12) earthly branches” AKA sexagenary cycle = combination of two cyclical systems used to name yearly calendar;

- (10 stems) 甲 (jiǎ)、乙 (yǐ)、丙 (bǐng)、丁 (dīng)、戊 (wù)、己 (jǐ) 、庚 (gēng)、辛 (xīn)、壬 (rén)、癸 (guǐ);

- (12 branches) 子 (zǐ)、丑 (chǒu)、寅 (yín)、卯 (mǎo)、辰 (chén)、巳 (sì)、午 (wǔ)、未 (wèi)、申 (shēn)、酉 (yǒu)、戌 (xū)、亥 (hài)

- 十面埋伏 (shí miàn mái fú) “total ambush” = idiom based on historical ambush of 項羽 Xiàng Yǔ by the army of 劉邦 Liú Bāng, who went on to found the Han dynasty; has been used as a name of a pipa melody, movies, pop songs, etc.

十二 (shíèr) = 12

- 時辰 (shíchén) - the day was traditional divided into 12 segments, and each two-hour interval was named after the 12 earthly branches (see above) and also paired with one of zodiac animals (see below)

- 子時 (zishí): 2300-0100

- 丑時 (chǒushí): 0100-0300

- 寅時 (yínshí): 0300-0500

- 卯時 (mǎoshí): 0500-0700

- 辰時 (chénshí): 0700-0900

- 巳時 (sìshí): 0900-1100

- 午時 (wǔshí): 1100-1300

- 未時 (wèishí): 1300-1500

- 申時 (shēnshí): 1500-1700

- 酉時 (yǒushí): 1700-1900

- 戌時 (xūshí): 1900-2100

- 亥時 (hàishí): 2100-2300

- 生肖 (shēngxiào) Chinese zodiac signs = paired with the 12 earthly branches to be assigned to a year; people born in that year are supposed to have personalities similar to the animal

- 鼠 (shǔ) Rat

- 牛 (niú) Ox

- 虎 (hǔ) Tiger

- 兔 (tù) Rabbit

- 龍 (lóng) Dragon

- 蛇 (shé) Snake

- 馬 (mǎ) Horse

- 羊 (yáng) Goat

- 猴 (hóu) Monkey

- 雞 (jī) Rooster

- 狗 (gǒu) Dog

- 豬 (zhū) Pig

二十四 (èrshísì) = 24

- 節氣 (jiéqì) solar terms = calendar developed to schedule planting and harvesting that also aligns with the equinoxes and solstices

- 立春 (lìchūn) Start of Spring - Feb 4th

- 雨水 (yǔshuǐ) Rain Water - Feb 19th

- 驚蟄 (jīngzhé) Awakening of Insects - Mar 6th

- 春分 (chūnfēn) Spring Equinox - Mar 21st

- 清明 (qīngmíng) Pure Brightness - Apr 5th

- 穀雨 (gǔyǔ) Grain Rain - Apr 20th

- 立夏 (lìxià) Start of Summer - May 6th

- 小滿 (xiǎomǎn) Grain Buds - May 21st

- 芒種 (mángzhǒng) Grain in Ear - Jun 6th

- 夏至 (xiàzhì) Summer Solstice - Jun 21st

- 小暑 (xiǎoshǔ) Minor Heat - Jul 7th

- 大暑 (dàshǔ) Major Heat - Jul 23rd

- 立秋 (lìqiū) Start of Autumn - Aug 8th

- 處暑 (chùshǔ) End of Heat - Aug 23rd

- 白露 (báilù) White Dew - Sep 8th

- 秋分 qiūfēn) Autumnal Equinox - Sep 23rd

- 寒露 (hánlù) Cold Dew - Oct 8th

- 霜降 (shuāngjiàng) Frost Descends - Oct 23rd

- 立冬 (lìdōng) Start of Winter - Nov 7th

- 小雪 (xiǎoxuě) Minor Snow - Nov 22nd

- 大雪 (dàxuě) Major Snow - Dec 7th

- 冬至 (dōngzhì) Winter Solstice - Dec 22nd

- 小寒 (xiǎohán) Minor Cold - Jan 6th

- 大寒 (dàhán) Major Cold - Jan 20th

二十八 (èrshíbā) = 28

- 二十八宿 (èrshíbā sù) 28 Mansions = ancient astronomers divided the night sky into quadrants (called 宮 gōng) using cardinal directions, and each quadrant named after the heavenly spirits (see above), contained seven constellations, and used to track the motion of the moon

- 青龍 (qīnglóng) Azure Dragon - east; determinative stars of each constellation: 角 (Jiǎo) Horn (α Vir), 亢 (Kàng) Neck (κ Vir), 氐 (Dī) Root (α Lib), 房 (Fáng) Room (π Sco), 心 (Xīn) Heart (α Sco), 尾 (Wěi) Tail (μ¹ Sco), 箕 (Jī) Winnowing Basket (γ Sgr)

- 玄武 (xuánwǔ) Black Tortoise - north; determinative stars of each constellation: 斗 (Dǒu) (Southern) Dipper (φ Sgr), 牛 (Niú) Ox (β Cap), 女 (Nǚ) Girl (ε Aqr), 虛 (Xū) Emptiness (β Aqr), 危 (Wēi) Rooftop (α Aqr), 室 (Shì) Encampment (α Peg), 壁 (Bì) Wall (γ Peg)

- 白虎 (báihǔ) White Tiger - west; determinative stars of each constellation: 奎 (Kuí) Legs (η And), 婁 (Lóu) Bond (β Ari), 胃 (Wèi) Stomach (35 Ari), 昴 (Mǎo) Hairy Head (17 Tau), 畢 (Bì) Net (ε Tau), 觜 (Zī) Turtle Beak (λ Ori), 参 (Shēn) Three Stars( ζ Ori)

- 朱雀 (zhūquè) Vermilion Bird - south; determinative stars of each constellation: 井 (Jǐng) Well (μ Gem), 鬼 (Guǐ) Ghost (θ Cnc), 柳 (Liǔ) Willow (δ Hya), 星 (Xīng) Star (α Hya), 張 (Zhāng) Extended Net (υ¹ Hya), 翼 (Yì) Wings (α Crt), 軫 (Zhěn) Chariot (γ Crv)

- 三十六計 (sānshíliù jì) 36 Strategems = a manual of military tactics

- 六十甲子 (liùshí jiǎzi) = one full cycle of the Ten Stem and Twelve Branches calendar system, since 60 is the least common denominator of 10 and 12

- 六十四卦 (liùshísì guà) 64 Hexagrams = the complete set of figures in the《易經》I Ching/Book of Changes, used for divination

- Archaic/alternate forms: 佰

- 百家姓 (bǎi jiā xìng) “Hundred Family Surnames” = published in the Song dynasty that ranks and explains the origins of the most important surnames at the time (a total of 507 surnames listed, despite the name of the book)

- Archaic/alternate forms: 仟

- 千歲 (qiān suì) “1000 years” = a subordinate’s greeting of empresses, royal concubines, and princesses

- 千古 (qiāngǔ) "thousand old" = throughout the ages; for all time

- the use of 千 (qiān) and 萬 (wàn) (see below) to form four-worded idioms to indicate ideas of “innumerous” and “countless” is popular:

- 千言萬語 (qiān yán wàn yǔ) “thousand words, ten thousand phrases” = too much to say

- 千軍萬馬 (qiān jūn wàn mǎ) “thousand soldiers, ten thousand horses” = a large crowd of people

- 千家萬戶 (qiān jiā wàn hù) “thousand families, ten thousand households” = every family

- 千秋萬歲 (qiān qiū wàn suì) “thousand autumns, ten thousand ages” = an eon

- 千絲萬縷 (qiān sī wàn lǚ) “thousand silk fibres, ten thousand silk threads” = countless links/ties

- 千真萬確 (qiān zhēn wàn què) “thousand truths, ten thousand definites” = absolutely true

- 千辛萬苦 (qiān xīn wàn kǔ) “thousand spicey-hot, ten thousand bitter” = countless hardships

- 千山萬水 (qiān shān wàn shuǐ) “thousand mountains, ten thousand waters” = long journey

- because Chinese has a specific term for 10,000 and the following factors of 10 use this as the base, it’s a mental shift when translating between Chinese and English; so:

- 十萬 (shíwàn) = 10 x 10,000 = 100,000

- 百萬 (bǎiwàn) = 100 x 10,000 = 1,000,000 (one million)

- 千萬 (qiānwàn) = 1000 x 10,000 = 10,000,000

- 萬歲 (wàn suì) “10,000 years” = a subordinate’s greeting of the emperor; consequently, the emperor can also be referred to as 萬歲爺 (wàn suì yé) “venerable one of 10,000 years”

- 萬一 (wànyī) “one in ten thousand” = just in case, if by any chance

- this is the next level up—and again, the needed mental shift because it doesn’t correspond to 1 billion

- 十億 (shíyì) = 1,000,000,000 (one billion)

- found out recently that 21st century China has come up with new terms for factors of 10 even greater than one trillion (not listing them here)

三十六 (sānshíliù) = 36

六十 (liùshí) = 60

六十四 (liùshísì) = 64

百 (bǎi) = 100

千 (qiān) = 1000

萬 (wàn) = 10,000

億 (yì) = 100,000,000

兆 (zhào) = 1,000,000,000,000 (one trillion)

Chapter 8: Tangent - Translation of the Nirvana in Fire subtheme

Chapter Text

Re-watched Nirvana in Fire recently and made, yet again, another attempt at translating the lyrics to the haunting subtheme.

紅顏舊 Faded Beauty

(電視劇《琅琊榜》插曲 subtheme of "Nirvana in Fire")

曲:趙佳霖 melody: Zhao Jialin

詞:袁亮 lyrics: Yuan Liang

唱: 劉濤 sung by: Liu Tao

西風夜渡寒山雨 the night's west wind brings cold rain to the mountains

家國依稀殘夢裡 vague images of the home country in shattered dreams

思君不見倍思君 thoughts of thee unseen heightens longing

別離難忍忍別離 unbearable parting must be borne

狼煙烽火何時休 when will the beacon fires cease?

成王敗寇盡東流 victors and losers will ebb away

蠟炬已殘淚已難乾 the candle is consumed but the tears have yet to dry

江山未老紅顏舊 the kingdom is still hale but the beauty has faded

忍別離 enduring the separation

不忍卻又別離 not enduring yet still separated

托鴻雁南去 entrusting the southward-bound wild geese

不知此心何寄 with a heart toward a destination unknown

紅顏舊 the beauty has faded

任憑斗轉星移 despite the rotations of the big dipper and the shifting of the stars

唯不變此情悠悠 this love remains unaltered

There are so many references to proverbs, idioms, poems, and other allusions that I’ve been forced to do a much more literal translation than I’d prefer, but even with this more direct take, I think the underlying message comes through (well, I hope). The one thing I definitely sacrificed is the mirror imaging of words and compound words at the beginning and ending of individual lines—would’ve made the translation really long-winded, so I put function over form. Alas, I’m definitely no poet.

Chapter 9: Snapshot - Anti-Chinese Immigration Laws and other Sinophobic Sociopolitical Enactments

Notes:

(See the end of the chapter for notes.)

Chapter Text

WARNING: discussions of racism

The 19th and 20th centuries saw the rise of increasing sinophobic sentiment “in the West” and the enforcement of legalized discriminatory behaviours by several countries. Even though these laws were eventually removed, a lot of the racial tension still exists some hundred years later. Below are a few of the most well-known and well-documented instances of legal barriers that Chinese immigrants faced:

- United States of America

The Page Act of 1875 prevented Chinese women (and other “undesirables”) from immigrating to the USA because they were stereotyped as promiscuous, as prostitutes, as transmitters of sexually-transmitted infections (STIs; formerly called STDs, sexually-transmitted diseases). Women wishing to apply were subjected to humiliating interrogations, which mostly took the form of invasive medical examinations.

The Chinese Exclusion Act, approved on May 6, 1882 by the 21st President, Chester Alan Arthur, then became the first significant law in the USA that restricted immigration to the country based on race. The Act allowed for a 10-year ban of Chinese immigrant labourers; even though non-labourers could apply if they acquired certification from the Qing government that they qualified for immigration, practices made it extremely difficult for most who made the attempt. The Act also required that the Chinese who had already entered the country to obtain re-entry certifications. The Act defined Chinese residents as aliens and they were excluded from citizenship.

When the Act expired in 1892, it was replaced by the Geary Act (signed into law by 23rd President Benjamin Harrison), which granted another 10-year ban and was made permanent in 1902. Chinese residents were required to obtain certification of residence or face deportation. The Geary Act also imposed quotas for immigration based on country of origin; the Immigration Act of 1924 (AKA the Johnson-Reed Act or the National Origins Act) set the quota at 2% of any given nationality already residing in the USA, although those of Asian descent were excluded; in 1943, despite Congress repealing all exclusion acts, the quotas remained and for the Chinese, it was 105 per year. The Immigration Act of 1965 finally put a stop to the Geary Act.

The Immigration Act of 1917 (AKA the Asiatic barred Zone Act), passed on February 5, aimed to prevent “undesirables” (mostly Asian, Mexican, and Mediterranean immigrants) from immigrating to the USA. The Act (28th President Woodrow Wilson's veto was overridden by both the House and the Senate to become law) imposed an English literacy test and an $8 head tax for everyone aged 16 or older. The Act was not eliminated until the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1952 was passed.

Because the Philippines were an American colony at the time, the Chinese Exclusion Act also took effect there and all immigration from China was barred.

- Canada

The Chinese Immigration Act of 1885, implemented upon the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway in British Columbia, which employed many Chinese labourers, imposed a $50 head tax on all Chinese immigrants in order to discourage immigration and became the first legislation to exclude immigrants based on race. It was approved by the 1st Prime Minister of Canada, John Alexander MacDonald (who was a key figure in the creation of Canada as a Confederation on July 1, 1867). Ships carrying Chinese immigrants were only allowed one Chinese per person for every 50 tons of the vessel’s total weight; this is in contrast to those carrying European immigrants, which were allowed one for every 2 tons.

This head tax was further increased to $100 in 1900 and $500 in 1903. $500 was two years’ worth of wages for a Chinese labourer. To further put this into perspective, in 1909, the monthly wages, including board, of a White male farm hand averaged $33.69 (roughly $400/yr). Also, no other ethnic group was forced to pay a head tax. In total, roughly 82,000 Chinese immigrants paid nearly $23 million in head tax before the tax was removed.

Note that the Chinese immigration laws of 1881 in New Zealand and of 1855 in Victoria, Australia required £10 poll tax on Chinese immigrants; the regions of New South Wales, Queensland, and Western Australia followed Victoria’s example. Newfoundland, still a British colony at the time, passed the Act Respecting the Immigration of Chinese Persons in 1906 and introduced a $300 head tax that was not abolished until it joined Confederation in 1949.

Because the Chinese immigrant population continued to increase despite this punitive requirement, the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 (AKA Chinese Exclusion Act) was created and approved by 10th Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, and while it abolished the head tax, it also completely banned all Chinese immigration until 1947. It took effect on July 1, 1923, on Canada Day and was known as “Humiliation Day” for the Chinese immigrants living in the country.

The Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 only allowed four exceptions to the exclusion: students, merchants (who weren’t in laundry, restaurant, or retail), diplomats, and Canadian-born Chinese returning from education in China. Chinese immigrants were only allowed to be absent from Canada for two years and failure to comply resulted in being barred re-entry. Every person of Chinese descent was required to apply for an identity card within 12 months and failure could result in imprisonment or a fine up to $500.

1983 began a decades-long campaign to refund the head tax (the initial request for a refund was denied). On June 22, 2006, the Canadian government under the 22nd Prime Minister, Stephen Joseph Harper, finally issued an official apology for the head tax and other immigration restrictions, promising “symbolic payments”. In the end, only 789 received any form of payment in 2009 because only the head-tax payers or their spouses (if they are deceased) could apply for recompense; and of the 789, fewer than 50 received the $20,000 in compensation that the government had promised.

The two Chinese Immigrant Acts and other similar policies didn’t only limit the number of immigrants. Collectively, they denied the Chinese the right to vote, to practice law or medicine, to hold public office, to seek employment on public works, to own crown land, and so forth.

Even though the Chinese Immigration Act was repealed in 1947 in the light of the end of WWII and the establishment of the UN Charter of Human Rights and Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1945, immigration restrictions didn’t actually take full effect until 1967, when Chinese immigrants could finally be on equal footing as other applicants.

- Australia

The Immigration Restriction Act of 1901 required immigrants to the then British Commonwealth country (Australia achieved Federation in 1901, and Edmund Barton became its first Prime Minister, but did not become an independent country until 1986) to pass a dictation test: they had to write out a passage of fifty words in an European language; after 1905, the government officer chose the language for the applicant, who could be imprisoned for six months and/or be deported if he failed. Few were exempted because they were non-European residents returning from travelling overseas or were visitors to the country; these people were issued a Certificate of Exemption. The dictation test was not abolished until the Migration Act 1958 was passed under the government of Harold Holt.

The Act was initially triggered by resentment by local White labourers toward the mainly Chinese labourers hired to work in Victoria and New South Wales during the gold mining boom of the early 20th century and toward the Pacific Island labourers working in the sugar plantations in Queensland.

The Act became the first in a series of what are collectively known as the White Australia Policy, which deliberately aimed at restricting non-White (especially non-British) immigration to Australia. Laws such as the Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901 and the Aliens Deportation Act 1948 allowed “undesirable” peoples to be forcibly deported.

The Racial Discrimination Act of 1975, passed by the government of Gough Whitlam, finally made it illegal to discriminate against migrants based on their race, as a result of international pressure, although in reality, the practice of discriminating wasn’t made effective until 1982.

- Jamaica

The Chinese (again mostly men) arrived in Jamaica in three major waves: 1854-1884, 1900-1940, and the 1980s. The first wave were indentured labourers brought over to work in the sugar cane plantations following the British Emancipation of slaves of African descent. The second wave were businessmen.

The Jamaican government passed a law in 1905 to restrict the number of Chinese immigrants. In order to enter, the individual had to (1) register with immigration authorities prior to entry, (2) have a guarantor from a reliable shop, (3) provide an address and contact information upon arrival.

By 1931, the government stopped issuing passports to immigrants of Chinese descent. Between 1931 and 1940, additions were made to the immigration law, including (1) written and oral English Language test, (2) head tax, (3) medical examination to prove the applicant was physically fit and healthy.

The other British colonies that hired many indentured workers from China post-Emancipation were British Guiana (now Guyana) and Trinidad.

- United Kingdom

1906 marked the beginning of a series of anti-Chinese legislation in the United Kingdom that took the form of Chinese expulsion policies for ‘compulsory repatriation of undesirable Chinese seamen’, the first of which forced these Chinese sailors, who had been employed by the East India Company and begun settling in the late 19th century in ports such as Liverpool and Limehouse, to take a language test for employment; they were the only group subjected to this test.

The riots of 1919 saw the establishment of repatriation committees in several major cities, targeting people of Arab, African, Chinese, West Indian, and East Indian descent, and the hostility caused many of the Chinatowns to empty as the inhabitants abandoned them to return to China.

After WWII, the Home Office enacted the forcible deportment of Chinese seamen by often kidnapping them and putting them on ships scheduled to sail to China; this is in spite the fact that many Chinese seamen had served on naval ships or contributed to the war efforts in other ways during both world wars.

- Peru

Chinese indentured labourers were initially brought into Peru in the late 19th century, to work on the cotton and sugar plantations and the guano and silver mines.

In 1909, the Porras-Wu Tingfang protocol was enacted to restrict the number of Chinese immigrants. After WWII, immigration laws placed further restrictions on all immigrants and localization of landed ones forced them to adopt hispanic names and religions.

- Mexico

When the plan to have Europeans settle the northern desert of Mexico failed in the 1870s, Chinese “guest workers” were allowed into that region. In 1893, the Treaty of Amity, Commerce and Navigation gave Chinese immigrants equal rights as Mexican nationals and resulted in a major wave of Chinese immigration between 1895 and 1910, many from the USA in the wake of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Starting in 1901, the Colorado River Land Company, created by Los Angeles investors, developed the Mexicali Valley and employed a lot of Chinese workers. As they settled in northern Mexico, the Chinese labourers gradually became merchants and landowners. They also began moving to other parts of Mexico.

Antichinismo sentiment started rearing its head with the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), whose goal was to overthrow the 30-year dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz and establish a constitutional republic but which resulted in a broader redefining of the socioeconomic structure and cultural identity of Mexico. Setting definitions of what “Mexican” meant caused racial tensions to escalate (because the new class definitions excluded Asians), and this was further fueled by economic hardship resulting from WWI and the Great Depression.

In the state of Sonora, the Treaty of Amity, Commerce and Navigation was nullified in 1921 to prevent further immigration from China to the region; in 1929, the state prohibited all foreign manual labourers from entering.

Beginning in the 1920s, the Chinese were forced to live in ghettos in Mexico City and other areas. Deportation started in the 1920s and turned into a mass movement in the 1930s, with almost 70% of Chinese and Chinese-Mexicans forcibly expelled from the country.

Chinese Diaspora

The Qing Dynasty Qianlong Emperor ruled from 1735 to 1796 and by the time he died, the treasury, which had been diligently added to by the previous emperors, especially his father, the Yongzheng Emperor, had been emptied to support his extravagant lifestyle, which included the purchases of his horde of precious antiques. This calamity of emptied coffers coincided with the height of European colonial expansion across the globe and the “China fever” that had overtaken European society mad about all things Chinese, especially silks, tea, and porcelain. The Qing government ignored the pounding on the door from Europeans demanding trade—the country was self-sufficient, having its own supply of natural resources and a strong and bustling trade along the Silk Road with the Middle-Eastern traders.

The British, paying through the nose via the East India Company with silver for Chinese luxuries, finally hit upon a commodity that the Chinese were (illegally) willing to purchase: opium. When it became obvious that mass addiction was hampering the economy both through decreased productivity and the loss of money, the Qing government attempted to put a stop to the illegal drug trade by destroying opium stocked in the warehouses in the city of Canton (now known as Guangzhou), the only port opened to the Europeans for limited trade. The British retaliated with a declaration of war and this started a domino effect and the “Century of Humiliation” that the Chinese suffered, triggering the mass Diaspora out of China beginning in the mid-1800s.

Here are some significant events that caused the Chinese Diaspora, which resulted in the 60 million overseas Chinese now spread across the globe:

1839 to 1842: First Opium War

- Treaty of Nanking 1842: ceded Hong Kong to the British, opening of treaty ports of Shanghai, Canton, Ningbo, Fuzhou, and Xiamen (Amoy) for European traders, $21-million dollar payment for reparations to the British, extraterritoriality for British citizens (they were subject to British, not Chinese, laws) residing in treaty ports

1856 to 1860: Second Opium War

- Treaty of Tientsin 1858: reparation payment, 10 more treaty ports, legalized opium trade, travelling rights within China to foreign traders and missionaries

- Burning down of Old Summer Palace and Summer Palace by the British troops under Lord Elgin (instead of the original plan of burning down the Forbidden City)

- First Convention of Peking 1860: between Britain, France, and Russia; cede Kowloon to the British, re-establishment of British and French missionary and charitable agencies, cede Outer Manchuria to Russia

- Second Convention of Peking 1898: between the British and China; leasing New Territories and other islands in addition to Kowloon and Hong Kong islands free of charge for 99 years; triggered the “scramble for concessions” by other countries including Russia, Germany, France, and the Empire of Japan for territory

August 1883 Eruption of Krakatoa, Indonesia

- resulted in global volcanic winter, darkened skies for years

1894 to 1895: First Sino-Japanese War

- primarily for control of Korea

- Treaty of Shimonoseki 1895: China recognized total independence of Korea, ceded Liaodong Peninsula, Taiwan, and Penghu Islands to Japan "in perpetuity", 200 million taels (8,000,000 kg/17,600,000 lb) of silver as war reparations, permission for Japanese ships to operate on Yangtze River, to operate manufacturing factories in treaty ports, and to open four more ports to foreign trade

1900 to 1901: Eight-Nation Alliance

- in response to the Boxer Rebellion to get rid of foreign missionaries and nationals, war was declared against China by Britain, France, Russia, the USA, Japan, Italy, Germany, Austria-Hungary

- Twenty-One Demands 1915: by Japan for further political and commercial privileges

1911 Revolution (AKA Xinhai Revolution)

- End of Qing Dynasty and establishment of Republic of China

- Dr Sun-Yat Sen became President, but he resigned in 1912 and Yuan Shikai, general and former Prime Minister of the Qing, became President; Yuan declared himself the Hongxian Emperor in 1915, although he was forced to abdicate in 1916 and the Republic was re-established

- Despite the end of dynastic rule in China, standards of living did not improve

1916 to 1928: Warlord Era

- Following collapse of Qing Dynasty and despite establishment of Republic of China in 1911, the death of Yuan Shikai in 1916 resulted in a power vacuum, and military leaders carved up the country into spheres of influence that they ruled; resulted in civil wars; many of their subordinates became sanctioned bandits

- Many of these military leaders served under Yuan Shikai; others were the results of Qing military reforms in the 1850s due to the Taiping Rebellion, when regional provincial governors were permitted to raise their own armies

- The Kuomintang (KMT) was created during this era by Dr Sun-Yatsen, whose protege, Chiang Kai-shek, would later retreat to Taiwan following defeat by the Communist Party led by Mao Zedong; his son Chiang Ching-kuo established the Republic of China in Taiwan

1929 Sino-Soviet conflict

- Between Soviet Union and warlord Zhang Xueliang over Chinese Eastern Railway in Northeast China

1927 to 1949: The Chinese Civil War

- between the Kuomintang (KMT)’s Republic of China government (under Chiang Kai-shek) and the forces of the Chinese Community Party (CCP) (under Mao Zedong)

- resulted in the KMT’s defeat and retreat to Taiwan and victory of CCP, the Chinese Communist Revolution, and establishment of the People’s Republic of China

- KMT and CCP did join forces during Second Sino-Japanese War

1937 to 1945: The Second Sino-Japanese War

- led into involvement of both countries in WWII

- Among battles between China and the Japanese were the Marco Polo Bridge Incident 1937, Battles of Beiping-Tianjin and Shanghai 1937, the Nanjing Massacre 1937 (“Rape of Nanjing”), Battle of Taierzhuang 1938, Battle of Wuhan 1938, Battle of Shanggao 1941, Battle of Changsha 1941

1939 to 1945: World War II

- China joined the Allies to fight against the Japanese

- this marked the beginnings of the eventual repeals of the Chinese Exclusion Act and Chinese Immigration Act because the USA and Canada realized that China was not the enemy

Natural Disasters

Natural disasters were always considered bad omens that the current dynasty had lost the favour of the Heavens. Therefore, in addition to all the political upheavals that were disruptive to socioeconomic growth and stability in the waning years of the Qing Dynasty and the first half of the 20th century, there were also major natural disasters that further exasperated the livelihood of the populace and contributed to the Chinese Diaspora:

- 1850 Xichang earthquake, Sichuan, 20,650 deaths

- 1850-1873 famine triggered by Nian Rebellion, Taiping Rebellion, drought, and plague; 10–30 million deaths

- 1851-1855 Yellow River floods: caused river to change course, a major reason for Taiping and Nian Rebellions

- 1876-1879 Northern Chinese Famine, mostly in Shanxi, Zhili (Hebei), Henan, and Shandong, caused by drought; 9.5–13 million deaths

- 1879 Gansu earthquake, 22,000 deaths

- 1901 Northern Chinese Famine, Shanxi, Shaanxi, and Inner Mongolia, caused by drought starting in 1898 and was leading cause of Boxer Rebellion, 0.2 million deaths in Shanxi, worst hit province

- 1902 Turkestan earthquake, Xinjiang, 2,500-20,000 deaths

- 1906-1907 Chinese famine, northern Anhui, northern Jiangsu, 20-25 million deaths

- 1920 Haiyuan earthquake, Ningxia, 265,000 deaths

- 1920-1921 Chinese famine, Henan, Shandong, Shanxi, Shaanxi, southern Zhili (Hebei), 0.5 million deaths

- 1928-1930 Chinese famine, Northern China, caused by drought and wartime constraints, <6 million deaths

- 1931 Fuyun earthquake, Xinjiang, 10,000 deaths

- 1931 Yangtze–Huai River floods, affecting major cities including Wuhan and Nanjing, deaths (estimated up to 53 million) by drowning, subsequent starvation and cholera epidemic

- 1935 Yangtze flood, affecting Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi, Anhui, Jiangsu and Zhejiang, 145,000 deaths

- 1942-1943 famine, mainly Henan, caused by Second Sino-Japanese War, 0.7-1 million deaths

The Coolie Trade – Chinese indentured workers

DEFINITION: Indentured servitude is a form of labour wherein a person is contracted to work without a salary for a set number of years; if the indenture isn’t a result of debt repayment or judicial punishment, there is compensation once the terms are completed. The indenture should be entered into voluntarily.

The transatlantic slave trade was finally abolished on February 22, 1807, after the British House of Commons passed the motion, ending three centuries of enslavement of Africans by the British. However, slavery continued in the British colonies until around 1833.

When British plantation owners in the colonies no longer possessed a source of cheap labour, instead of paying a fair wage to freed slaves, they chose to create an indenture system that other colonialists, mostly French, Portuguese, Spanish, and Dutch, also began implementing. This system, also called the Coolie Trade (“coolie” is derived from the Tamil word kulī, meaning “hireling”; the Cantonese transliteration is 咕哩 gu lei), hired labourers from Asia and Africa, and between 1834 and 1920, roughly 1.5 million indentured labourers, of whom 750,000 were Chinese, were sent to the British colonies; the Chinese mostly ended up in Malaysia, Sumatra, Cuba, the British West Indies*, and La Réunion (the French colony in the Indian Ocean near Mauritius), although many ended up working in other countries including Australia, the USA, Canada, and Peru.

(*Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands, Montserrat, the British Virgin Islands, Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Jamaica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, British Guiana (now Guyana), Trinidad and Tobago, Bermuda, and the former British Honduras (now Belize))

Despite being defined as voluntary servitude, in reality, many labourers were kidnapped and sold as indentured labourers. The indenture contract could also be sold to another master. And given the harsh conditions of travel (for those conscripted due to debt slavery, as many as 500 were crammed into the small ships and up to 40% died en route) and subsequent poor living conditions in the colonies, this was a new form of slavery.

Between 1848 and 1873, Portuguese Macau was the centre of the indentured worker trade.