Chapter Text

NOW

Sophia stood looking at the red smear on the ice for a long time.

It was a few metres long, and that was mostly the drag marks: drops and smears and pink slush surrounded it. She assumed, from half-remembered nature documentaries, that it had been a seal once. But now there was little left of it even for scavengers to pick over, and whatever bear had eaten it was probably long gone.

Even so, she was very glad to be inside. She’d had no idea they got wildlife this close to the launch pad.

She could picture the seal’s death: the wrong turn underwater, or perhaps a long, exhausting chase; head engulfed in the bear’s mouth, skull pierced through with canine teeth, the sudden darkness and the fatal crush. Dragged to the surface afterwards, its trailing weight between the bear’s front legs forcing the bear to waddle until it came to the spot of its choosing, dropped its prey, looked around, and began to eat. Well, good for the bear, she supposed: God knew there were few enough of them around, any more.

Some time ago, probably in a course on art history in undergrad, she’d heard about some artist one-upping another at an exhibition by adding a little dot of vermilion to a painting of the sea, thereby fascinating more onlookers than his rival (Turner, maybe?). Sophia wasn’t an artist; she was a writer. But journalism came with its share of arresting images, and a stark spot of red amidst all that white certainly held the attention, even through a thick glass wall.

“Sophia Cracroft?” somebody said.

Sophia was too disciplined to startle; instead she looked around with an automatic smile. Her new escort was an Inuk man, with the name KOVEYOOK neatly embroidered on his uniform patch beside the Commonwealth Space Commission’s logo. She thought she recognised the name from the files she’d read on the way over. Sophia stuck out her hand, and he shook it. “It’s good to meet you,” she said, and hazarded, “Will you be the Lyra’s flight engineer?”

Koveyook smiled widely and said, “That’s right,” and Sophia felt herself relax almost reflexively. “And you’re our reporter, huh? I think I read one of your features about Mars, a few years back. You got a prize or something, right?”

She’d won the Orwell Prize and been nominated for a Peabody, in fact. It had been the highlight of her career, a reward for two gruelling years of investigation and damn near missing the rocket launch that could take her home again. Koveyook had clearly read up on her before she arrived.

He had a friendly, reassuring presence; the kind of person, she assumed, who was perfectly pleasant to travel with for months or years. Her uncle had the same kind of manner. He’d always told her that being easy to get along with was one of an astronaut’s most underrated skills.

“That’s right,” Sophia said, allowing herself a modest shrug. “I’m going to be writing features on this mission as we go.”

Koveyook waved a hand in the direction of the security doors and said, “Sounds like interesting work. Come on, I’ll take you to see Ross.”

Sophia followed him, answering friendly queries about her flight and accommodation, her work, her perspective - far too nice and lighthearted to be an interrogation, but it was obvious that Koveyook was trying to get an impression of her. It occurred to her that there were likely several people lower on the totem pole who might have been sent to fetch her.

She kept her face fixed in a light, agreeable expression that she had perfected through years of practice: open, receptive, and curious, all the things that put people at their ease. It was her interview face, her camera-ready face, her face for deescalating confrontations and accepting awards alike. She saw it reflected in the retinal scanners of each security door they passed through, and it stayed in place all the way to Sir James Ross’ office, where Koveyook told her he was pleased to have met her, and left her at the door.

The expression even survived the moment when Ross looked up, recognised her, and said, “Ah,” in a way that, for the space of a single syllable, could not disguise his dismay.

She stayed smiling, and held out her hand again. “Good to see you, Commander,” she said, “It’s been years. How’s Ann?”

“She’s well,” Ross said, shaking her hand, while his face cycled through a variety of emotions before settling on resignation. “Very well, thank you. So you are the journalist that Lady Jane is sending with us?”

“You didn’t know?” Sophia said.

“And that’s not a conflict of interest?” he asked.

“Not according to my editor,” she said, still smiling.

“Of course,” he said, patting his thighs in a gesture that was almost, not quite, like wiping his hands. “Well then, have a seat,” and he gestured at a chair by his desk.

It was a surprisingly pokey little office, now she was looking around it: a lot of screens (she glimpsed graphs on one, a live feed of what seemed to be the rocket lab on another), a surprising amount of paper, two tablets (one of which displayed something she thought might be flight path calculations), and a series of model spaceships. She thought the models might actually be hand-painted, and amused herself for a few seconds imagining the great Sir James Ross hunched over a kitset wielding a fine-pointed brush.

He cleared his throat, tapping at his keyboard, and said, “When was your last spaceflight?”

“Two years ago,” she said. “It was just a jaunt to the moon, to cover the Ullrich decompression incident, but I have gone further before, of course.”

“Mm,” he said, eyes fixed on the screen. He knew about her time on Mars. “Have you requalified?”

“I passed the psychological evaluation three weeks ago, and the physical last week,” she said briskly. As if the CSC would have accepted her for the mission without either of them. She tilted her head and eyed him. “You really didn’t know I was coming.”

Ross sighed, and sat back. “We’ve had to rather crunch the planning of this mission; as such, I have focused on the ship and the selection of our command crew. That does not include participants such as yourself - I left that up to the Commission.”

“Mm,” Sophia said. He was going to command the Lyra - he ought to have dossiers on all his crew by now. The information must have been available to him, because Koveyook knew who she was. This interview was supposed to be a formality, it was true - her qualifying meetings had taken place in England a fortnight ago - but that only meant that there had been several weeks in which he might either have sought out the information or had it mentioned to him. She suspected ‘crunch’ might be putting it mildly: this must be the first time he’d come up for air.

“Lady Jane stipulated that she was sending a journalist along with us. I didn’t find it strange that she’d want some public accountability, considering...” He hesitated.

Sophia waited, and then said, “Considering that she’s funding it?”

“Most of it,” Ross corrected. “But yes. A journalist was the string that came attached to the funding.” He looked away for a long moment, and then back to her. “I didn’t ask. It occurred to me that it could be you. I just didn’t think she’d risk you.”

Sophia let herself stop smiling.

The thing about knowing someone since she was a bright and shining undergraduate was that there was space and time for her to have turned into a completely different person, and for him to not have noticed. Was she still nothing but Lady Jane’s niece in his eyes?

God, she’d had such a crush on Ross when she was young - a really heady infatuation that had felt so true and mature at the time, and that was only saved from disaster by the fact that he’d never deigned to notice. Of course, then she’d gone after his best friend instead, which had been rather good until it had gotten messy. The thing was, even with the way it had ended with Francis - all the things they hadn’t been able to give up for one another - she didn’t think of that as a disaster.

It occurred to her that Ross might. Which, everything else aside, would be very inconvenient at this moment.

He looked at her, and she looked back at him, and she let the silence spool out for just long enough to get uncomfortable before she said, “My aunt doesn’t tell me where to go. My editor does.” Another pause. “Is this going to be a problem?”

He blinked first. “No,” he said. “You’re qualified and experienced, and you’re here to do a job.”

“Yes, I am,” she said.

He sat back in his chair, and she let herself mirror him. “You know the mission brief?” he said. “The timeline?”

She recited, “The Jupiter satellites have told us that Erebus is on her way home early, with a trajectory that is predicted to get them to Mars where they will likely need to refuel. We are to intercept, aid if necessary, and investigate why we’ve had no transmissions since the day after they landed on Europa. If nothing unexpected happens, we should rendezvous with Erebus in thirteen months’ time and be back here inside three years. But sod’s law says something unexpected will happen, so we’re equipped for a five-year mission. Have I got that right?”

“Yes,” he said, “Near enough.” He hesitated, worked his jaw, and said, “Except for the bit about the transmissions.”

THEN

Silna awoke on the 376th day of the journey and thought, not for the first time, I can’t do this forever.

In the dark of her sleeping pod, she sat up. The air cycled cool over her face, and the motion sensor brought the light on, very low at first and getting brighter as she sat and squinted in her little box. Faintly, through the walls and beyond the little door, over the ever-present hum of Erebus’ engines, she could hear voices.

She’d been dreaming. She couldn’t remember much, but she’d been alone, headed towards the horizon: a dark line of water beyond the snow, but it seemed to curve away from her, up and up as if on the inside of some huge wheel. She hadn’t seen a horizon in so long. Even longer since she felt that kind of peaceful solitude.

The voices outside sounded excited. Silna spent a couple of minutes blinking at the screen at the foot of her bed, which had come on with the lights. It was doing what she’d programmed it to do on standby, cycling through pictures she’d put on there, mostly of home, her dad, her colleagues, pictures she’d taken out on the ocean.

Like she was trying to make herself homesick.

She wiped the crusts out of her eyes and swung her legs out of bed, into the tiny strip of floor that constituted all the private space she had outside of her bunk. It had taken her weeks to learn how to get dressed without whacking her elbows on something, but it was still a pretty luxurious amount of personal space by the standards of spaceflight. Some company ships still strapped their crews into bags in zero gravity. This was a multinational government contract: it was cushy.

Her heels bumped the drawer where she kept her personal items, and she felt the answering clunk from the soapstone qulliq that she’d sacrificed a third of her weight and volume allowance to bring along, even though she had no way to light it, and no intention of trying on a spaceship. Occasionally, it felt like an absurd thing to bring in place of something she could use. But she remembered going on her first long space flight with her dad when she was a teenager, and he’d brought his then. She hadn’t seen the point of it, until he said, Space is the coldest, darkest place we can go. So the ship has to be home, right?

Right.

She wished her dad could have come along. He’d been representing the territory for so long, and then got sick two months into the training simulation, had to be evac’d out. And he was better now, but better wasn’t a passing physical. So it was just Silna now. And she missed her dad, and felt stupid for being a grown adult with a PhD on the most exciting opportunity of her life missing her dad, and angry at herself for feeling stupid, around and around like a whirlpool.

She swung her heel back just to hear the clunk again.

It was no good to wish she was somewhere else. She was here, so here was home, and she had work she had to do.

She scraped her hair back from her face and spent a few minutes pulling it out of the sweaty braid, combing it, and re-braiding it. Then she tugged at her sleep clothes until she was sure she wasn’t showing underwear, and stood up. She hit the switch on the wall to turn the lights and screen off at the same time she tugged open the door.

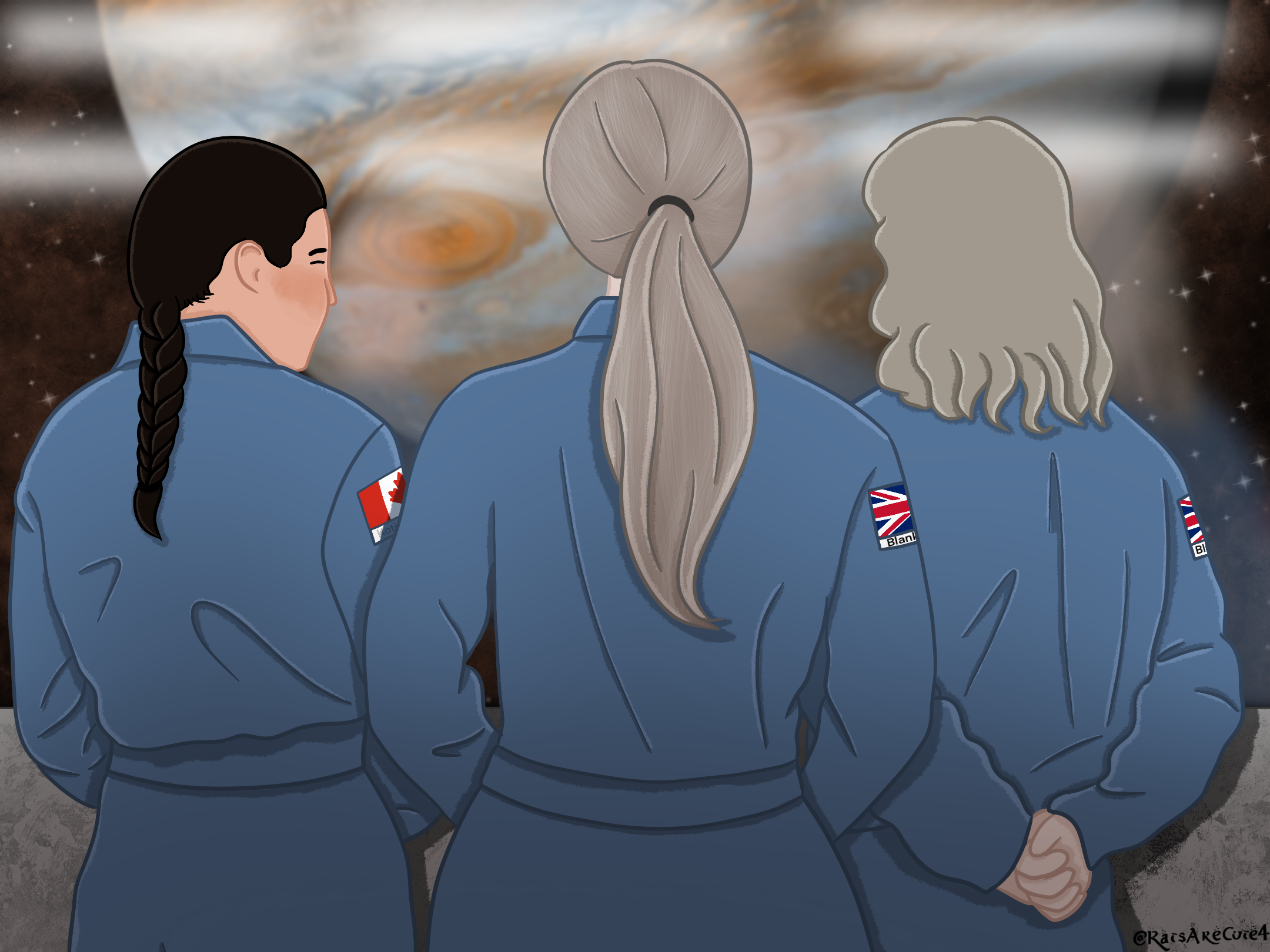

The bright lights of a daytime cycle on Erebus’ residential ring made her eyes water a little, and the noise got a whole lot more obvious. The floor and ceiling curved away in either direction. She shuffled down the little corridor of sleep pods, where other crew were stirring, and saw Esther Blanky standing on the cushioned pad on top of her own pod, hands on her ample hips, grinning out at the windows.

“What’s happening?” Silna said, looking up at her.

“We’ve made eye contact!” Esther said, gesturing clockwise. “It’ll come around again in a minute.”

Silna leaned against the wall, rubbing her eyes, as Thomas Blanky emerged from Esther’s pod. Silna presumed he’d spent the night there, squeezed in and happy, and frankly, she was just glad he had bothered to put his shorts back on. They’d all lost a lot of formality, travelling together for over a year - at first it was all politeness, wriggling into their flightsuits in the confines of their pods before stepping out to greet each other, but nowadays only a couple of the more senior astronauts still bothered (and it was rumoured Commander Franklin slept in uniform). What made it worse was that all the pods had been built for single occupancy, despite the handful of married couples on the crew, and that didn’t take into account how much the singles liked to mingle. She’d gotten an eyeful more than once from some of these guys heading back to their own pods in the small hours without bothering to put their clothes back on, just bundles of cloth clutched to their nethers as they sprinted bare-assed down the ring to hoots and whistles from the rest of the crew. Thomas and Esther were right next to each other, but they were also shameless.

“Eye contact?” she asked, as Blanky climbed up and sat down by his wife with his prosthetic leg stretched out in front of him.

“Rite of passage! You’ve not been out this far before,” Blanky said. (It wasn’t a question: they all knew by now which of the crew had never been further than the asteroid belt, or Mars, or even the Moon.) “Now you’ll be able to say you’ve looked Jupiter in the eye. Here it comes!"

And there it came, as the ring rotated. Jupiter was always visible to the naked eye, and they had satellites in geostationary orbit above the Europa facility that beamed back images of the moon and Jupiter that they could access whenever they wanted. But now they were close enough to see the great red spot swirling in its gasses, glaring at them across the millions of miles. A handful of other crew were walking down the ring to follow it, but Silna barely paid them any attention, because she was so arrested by it. It really did seem like it was staring at her, and she felt compelled to walk right up to the window so she could stare back.

Erebus was, from every standpoint, maybe the best possible ship to spend years of your life on. The double rings rotated to provide a decent simulation of gravity for the living and laboratory areas, and the windows let her see stars in every direction. If she didn’t want to jog loops around the rings, there were VR headsets attached to the exercise machines so that she could pretend for a little while that she was running through a forest or cycling along a coastline. They all had duty rotations in the food garden so that they could touch something green and living once in a while. Their combined pool of films and shows, which one of the comms guys, Bridgens, had taken pains to correctly label and organise for ease of use, allowed them to run movie nights and genre binges without ever having to repeat viewings, except on popular demand. It still wasn’t enough to stop her from wanting to climb the walls from time to time - which was also an encouraged activity in the right circumstances, but the point was. The point was. Silna wanted off this ship.

The sight of Jupiter this close, meant that it was happening soon. Intellectually, she’d known it, but it was another thing to see it.

“And there’s Europa,” Blanky said, pointing to the gleaming white dot emerging from the shadows, picking it out from among all of Jupiter’s moons. “A few months now, and we’ll be on solid ground again.”

Silna muttered fervent thanks for that in her own tongue, the same one she mouthed every time she’d ever landed back on Earth with all her limbs attached - which Blanky and Esther understood well enough that they laughed in agreement.

There weren’t a lot of people on Erebus who spoke her language. She’d gotten used to career astronauts who hung around the CSC bases in Nunavut, who tended to learn at least a little, and since she didn’t spend a whole lot of time socialising with Captain Crozier, their flight engineer, the occasional exchange with Thomas and Esther was one of the few ways she got to have a conversation in her own tongue. Funnily enough, the Blankys had started out in commercial asteroid-mining just like her dad, a different path from the professional astronauts on this crew who’d started out in a national aeronautics agency, or her fellow researchers who’d only ever been passengers.

Erebus was ostensibly a pan-commonwealth project, but in practice it was one of the whitest crews she’d ever been a part of; most of the crew was British, with one Irishman (she had learned the distinction was important), a handful of Australians and Canadians, and one half-Brazilian payload specialist, Fitzjames, who she was pretty sure had grown up in Brighton and attended the same school as half the other career astronauts aboard. Silna was certainly the only Inuk aboard, and the longer she went without speaking Inuktitut, the more paranoid she felt that she might forget how. One way she kept it up was by teaching it to Harry Goodsir, and here he came now, part of the scrum chasing Jupiter around the turning ring, curls in his eyes and sheepskin slippers on his feet. He spotted her and said, “Ullakkut!” the way she’d taught him to, and it still made her smile.

Over his shoulder, she caught the eye of Lieutenant Gore, the pilot. She’d heard he and Captain Fitzjames used to climb mountains together, and absolutely believed it: he was one of those intensely energetic guys who managed to give off the impression that he was kicking around a soccer ball even when he was in the middle of an astronavigation lecture. He jogged towards them, waving up to the Blankys, and said, “I was just saying, Isn’t it brilliant that we get to see that spot with our own eyes? It’s only been going for a few hundred years, and probably won’t last much longer. And we developed space travel in that window of time! We’re so lucky.”

“It’s a lucky solar system, when you think about it,” Harry said, placidly. “I think the size of the moon relative to the distance of the sun is still my favourite thing - what a lovely coincidence, that they look the same size from Earth.”

Silna’s personal favourite coincidence was that she got to be alive at the same time as the blue whale, which as far as anyone knew was the biggest animal to ever exist. She liked to tell that one to little kids - but it didn’t have anything to do with the solar system. She turned her head to the storm and said, “Looks like it’s staring right at you.”

“Ah, to be around when it blinks - that might be interesting too,” Esther said. “Storm’s got to collapse at some point.”

“Aye, but another will pop up, most likely,” Blanky said. “Hairy ball theory, isn’t it?” which made Esther snigger.

“One eye closes and another opens,” Gore said. “Imagine where it’ll go next.”

And it was around this point that the rest of the crew came crowding in to follow Jupiter around the station, sweeping Harry and Gore up in it, and Silna took it as a sign to put some real clothes on and go get breakfast.

The commissary was in a spot between two of the sleeping areas, and it was unusually crowded for this early on the day shift. At least, she thought it was, until she looked at the clock and realised she’d woken up early enough to catch the night shift having their supper.

Silna heated up a ration pack of mackerel and another one of scrambled eggs, picked something hot and astringent from the tea selection, and carried it over to the corner of the least-occupied table. She sat down with a polite nod to its only other occupant: Crozier, who paused in scraping something brown out of the bottom of a silver bag to spare her a nod back. Amid the clatter of the commissary, they ate in a little bubble of mutual silence, until Silna had finished the fish and was poking at the packing-foam blob of eggs, and Crozier started piling up his empty packs.

Something compelled her to ask, “Not long now?”

He paused with a faint look of surprise, then with a small smile said, “Forty days, give or take.”

She nodded, trying not to let her relief show on her face. It was a little embarrassing to tell the flight engineer how much she wanted off his ship. “Be good to do what we came to do,” she offered.

Crozier nodded like maybe he bought that, or maybe he didn’t, but he’d allow it either way. “Be interesting to see what the drill brings up,” he said.

That was an understatement. As far as Silna understood it, the Europa ice drill, which was even now boring a hole through the 25 kilometer-thick crust, was Crozier’s special project going back decades. He’d been around for its design, conception, and development, and his last Europa mission had been spent deploying it, and setting the machines down on the surface to build their habitat. She didn’t know much about that kind of engineering, but apparently it was complex enough that they couldn’t just program the machines and let them run, and they couldn’t control them remotely from Earth because of the huge time delay between Earth and Jupiter. So the last mission to Europa had been Crozier, Blanky, and a bunch of other engineers sitting in orbit above it, remote-controlling machines the size of multi-story buildings on a surface with ice fissures big enough to swallow any one of those machines whole.

At least, that was the impression she’d gotten. The seminar had been a while back, and unlike Fitzjames (who seemed convinced that everyone was as interested in rockets as he was) Crozier wasn’t inclined to repeat lectures with the same audience.

Silna thought this, nodded, and resumed digging eggs out of the foil bag.

But before he left, Crozier asked, “What are you hoping we find?” He emphasised the you, like it was a question he asked everyone. Probably it was. But he had to know it was a hell of a question to ask her.

Silna was here because she was a marine biologist who specialised in the life that formed around hydrothermal vents, the kind so far from the sun that it didn’t factor into the food chain. If Europa had life, it would almost certainly have to originate around those kinds of vents. She was here to test for signs of life in the ice core samples, and then eventually in the seawater if they managed to drill down far enough to drop probes. At the very least, she hoped for CO2 bubbles and heavy metal traces that could indicate the right biogeochemical processes were happening.

But there were a whole lot of marine biologists in the world, so the other reason Silna was here was because she represented Nunavut’s interests in Europa’s water ice. Whatever countries - or companies - managed to land representatives to work on the surface of a celestial body got a claim on that body. Boots on the ground meant resource shares. And since water was in demand wherever humans went, it was very, very good to have a claim on a body with abundant ice.

The ice was vanishing from Nunavut now. You could cruise from Greenland to Russia most years, and people did, and the tourism helped, but it wasn’t enough to make up for everything they’d lost - the coastlines, the fauna, the ways of being and doing. The terms that let the CSC build infrastructure on Nunavut also meant that whatever missions went up with personnel, one of her people was on it. That meant whatever rock they set foot on, Nunavut got a claim.

So Silna was here. Hoping with one half of her heart for proof of alien life beyond her wildest dreams. Hoping with the other half for nothing but pure water ice, enough to secure their future for decades or more.

She said, “Maybe tube worms.”

Chapter Text

NOW

The Devon Island Europa Simulation was rarely referred to by its acronym, for obvious reasons that Sophia thought should have prompted someone in the CSC to rename the damn thing long before Erebus left Earth’s orbit. They could have called it the Tallurutit Europa Simulation and nobody would have gotten morbid about it.

From a distance, the Europa Simulation looked like a cluster of barnacles, clinging to what was left of the Devon ice cap. Inside, it was a one-to-one replica of the robot-built habitat on the surface of Jupiter’s moon. Every hallway, hatch, bunk, lab, cupboard, and cranny that Erebus’ crew would find there was built here, just to test that the prospective crew members would be able to stand a full year of each other’s company in an enclosed habitat with peculiar procedures, and ingrain in them the muscle-memory necessary to carry out emergency procedures under any circumstances.

Testing new-build space habitats like this was standard safety practice for older space agencies. It was the kind of thing that distinguished an extraplanetary research facility from more corporate infrastructure, where all kinds of awful shit could happen.

Still, she supposed that if it turned out that any of the hundred-strong crew hated each other’s guts, it was better to find out while they were still on the surface of Earth. There had been three drop-outs for health reasons in that time, but nobody had failed the psych tests on exit.

Of course, it wasn’t a perfect simulation: they couldn’t simulate Europa’s weak gravity, or the violent surface radiation, and even here on Devon Island, where the compasses spun around a constantly wandering magnetic pole, the weather could not approach Europa’s surface temperatures of -177 Celsius (and that, she recalled her uncle telling her, was a balmy day at the equator).

The idea of the habitat on Europa had been that it would host a succession of crews, rather like an Antarctic research station, with new blocks of researchers fired off in a rocket whenever the planets were aligned - as long as they could pass a season in this place first - and act as a base for long-term ice mining. Right now the simulation was abandoned, pending the resolution of their investigation into Erebus’ disappearance. But the lights still turned on, and all the hatches still opened. Sophia stood in its wide hallways and took pictures.

She had access to a floorplan, of course. But it was different, being able to stand inside it.

The hallways were more spacious than she thought they’d be. It echoed. But she could see wear marks in the paint on certain areas of the wall, perhaps where multiple bodies over the course of a year had habitually put a hand out, or leaned their weight in mid-conversation. She found the mess hall: above the door, someone had painted the words “ARK EUROPA” and a little sailing ship. She wondered if the sign painter had replicated it on the real base. She snapped a picture.

She wondered if the sign painter had attempted to send back pictures of their own.

She called up the floor plan again and squinted at it, trying to read the text on the tiny screen. Annoyed at herself, she asked, “What does the control room look like?”

Ross, standing with arms folded in his bright red parka, said, “This way,” and led her down another corridor and then up a staircase, until they came to a room that she realised must be right above the common room, which explained her trouble reading the map. There were two doors, and the walls were otherwise covered in screens. All black now, of course.

“It must have good soundproofing,” she said, because it was the first thing that came to mind. Otherwise the noise drifting up from the common area would surely make this the worst possible place to stick the communications shift.

“It does,” said Ross. “They got to test for it.”

“And absolutely everything would be transmitted through here,” she muttered, looking about. There were scuff marks faintly visible on the floor, she noticed. Some equipment looked like it had been disconnected; a few screens were at an angle that would be nobody’s ergonomic preference, but would allow a tech to unplug something from the back. “I assume your lot ran tests on it all when the communication failures became apparent.”

“Of course we did,” Ross said, sounding a touch impatient. “That was part of the initial inquest. Surely you’ve read it.”

She had, but not closely enough, apparently, to notice just how much work the word ‘intelligible’ had been doing in those initial reports. ‘No intelligible transmissions’ from the surface of Europa. They had sent weekly reports on their continued failures to receive anything coherent to Aunt Jane until she’d told them to stop and come back to her when they had something positive to report, and then they never had.

That had been about the point when her aunt had started seriously campaigning for a rescue attempt. She got it, of course. But even Lady Jane Franklin, MP, hadn’t been able to influence the planets into a more favourable alignment.

For six months, all they’d had was that last look at uncle John, surrounded by his crew, all beaming with joy. A shuffle of photographs of a party in a dining hall on an alien moon, that she and every other family member of the expedition must have combed over for every trace, every crumb, of the last known fate of someone they loved.

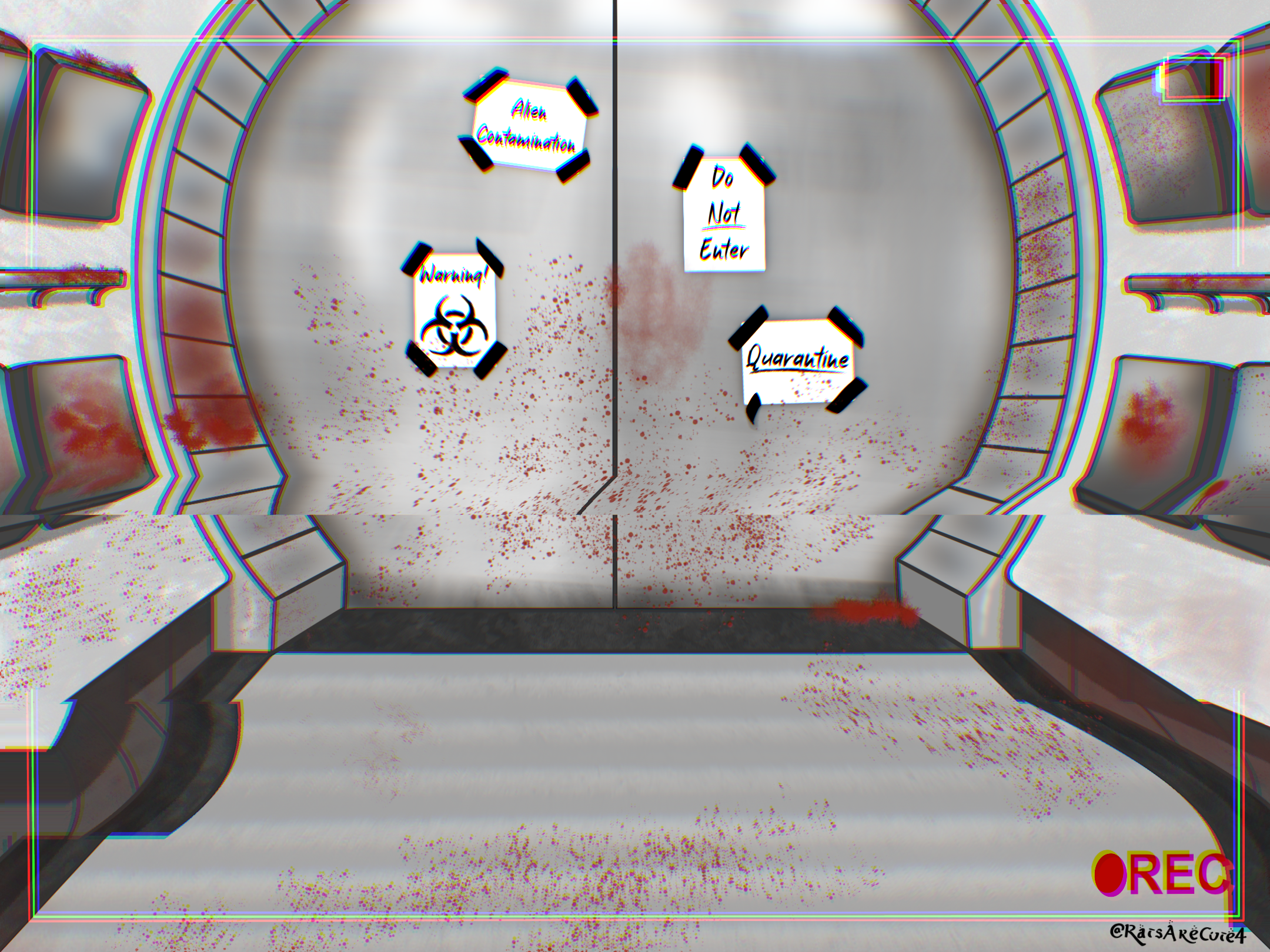

“I recall the speculation was of equipment failure at the site,” she said. That something had gone wrong with the robot-built double to this test site, undetectable by all the hundreds of sensors built into it and transmitting for the whole of Erebus’ journey. It invited all kinds of terrible speculation, for if something were to go wrong with building the transmitter, surely it could go wrong in life support, or leave the facility with structural weaknesses that would become deadly over time, letting out the precious heat and air, letting in the killing frost and deadly radiation.

“That was one theory,” Ross said. “It seemed plausible, early on, until the satellites told us that Erebus was coming home. Now, some kind of cascading software glitch seems more likely.”

He meant the satellites that belonged to other nations, orbiting other moons. The CSC satellites above Europa had gone dark two weeks after the Erebus crew touched down.

Sophia stood for a while with her arms folded, staring blankly at the blank black screens in front of her. This was what she hadn’t understood, for the last few years: the thing that had been downplayed or elided in the CSC’s reports. She didn’t want to use the word coverup, but she could feel the words seriously misled on the tip of her tongue. She had thought - the public had thought - that there were no transmissions from the Europa base after that first two days, but that wasn’t true. The radio bursts CSC had picked up were all on the expected channel and from the expected source, at expected times. It was just that those bursts were absolute gibberish.

Sophia said, “Did my aunt get to hear any of those transmissions?”

“Some,” Ross said, quietly. “She had the clearance for it. And now, so do you.”

So Aunt Jane got to hear those unintelligible packets of noise. The ones that sounded sometimes like scraping, and sometimes like shrieking, and didn’t sound or look any more like audio or video or any kind of coherent data no matter what program or filter they were run through or what expert assessed them. They were just noise. Horrible, horrible noise.

Sophia took more pictures. Rotely, she found good angles, interesting compositions, crouched, snapped. They’d look good in the feature article.

After a few minutes, there was a rustle of parka fabric, and Ross said, “You have twenty-six minutes left, and then we really must get back on schedule.”

THEN

“Now, I know you’re all very keen to get to work,” Sir John Franklin said, his voice buoyant and his face rosy in the warm light of the bar. “I can assure you, we are all eager to see the results of this project that is decades in the making,” and here he glanced pointedly - almost theatrically - at Crozier, who took the ensuing whoops with a bemused expression. “We have the privilege of being the first custodians of this research station, and surely there will be many more missions to come, all centred on this base. A bright and brilliant future of research lies ahead of us all. But I must insist you settle yourselves in, first!”

General laughter, and some cheering, from the whole assembled crew, shoulder-to-shoulder in the Europa common room. The real Europa common room. Silna was as caught up in the mood as anyone, thrilled to be here, finally here, at their destination. It was amazing. It was exciting. It was a huge relief.

It was also strange. This whole place was familiar - identical to the Tallurutit simulation down to the last hatch, at least on the inside - but with incredibly weak gravity. They bounced more than they walked. More than one person had misjudged their stride and careened into a wall or even the ceiling, and it was funny for now, but she bet it was going to get a whole lot less funny when they were moving delicate samples.

It sounded different, too. The walls of this base were incredibly thick - metres of concrete and insulation, and then metres more of ice, to shield them from the surface radiation. But under the expected hum of life support systems, there was also a persistent vibration, more felt than heard, that she had realised pretty quickly was from Crozier’s drill.

She’d caught a glimpse of it from the shuttle as they transferred down from Erebus: a monstrous apparatus, nearly half the size of the habitat, a combination of mining rig and tunnel boring machine that squatted above the ice a few kilometres from their base, hiding the borehole itself from view. It was many kilometres beneath the surface now, chewing and chewing, never stopping. No wonder that they could hear it, even now, crowded into this room together, with their mission commander mid-speech.

It was a hectic day. After Franklin had finished hyping them up, they all had a tight half hour to set up their bunks. As on the ship, they had their own rooms, though a little less tight: there was a metre-wide strip of floor, a fold-down desk and chair with storage straight ahead, and, to the side, a bunk either at ground level to your right or up a ladder on your left, depending on which of the interlocking L-shapes you’d been assigned. Silna had a ground level bunk, the opposite to what she’d had on Earth, and it occurred to her that they might all have been given the opposite kind of bunk to thwart muscle-memory that could send a person on Europa head-first into the concrete ceiling, when all they wanted was to climb a ladder fast. When she’d made the bed (weirdly difficult with almost-weightless sheets), she unpacked her clothes and personal items, putting everything neatly away - everything but the qulliq, which she set out on her desk.

She actually did feel better, seeing it there.

Time was up, and now they were on rosters to unpack their equipment and at least begin setting up their work areas. For Silna, that meant four hours shoulder to shoulder with the drill guys: Crozier, not allowed out to see his baby yet, was overseeing the assembly of the mass spectrometer in its own room, but had assigned his small army of engineers to help Blanky set up the hangar-sized ice core analysis lab.

The drill guys listened to Blanky and Esther when it came to wrestling the machinery into place - and putting up the shelves in the massive ice-core storage freezer - but were lousy at grasping the concept of anticontamination protocols. Silna glared at Hartnell around the third time he stepped on her plastic sheeting, and he backed up like she’d pointed a gun at him. But in her defense, there were miles of the stuff that still had to be hung up, and most of the drill crew was too preoccupied with cooing at the toys (conveyor belt, ice core melting system, chromatograph, laser water isotope analyser) to do the boring work of making sure all the surfaces those toys were on could be separated and sterilised.

The real lab work was going to have to be done in PPE. They were hunting for alien life here, and there was going to be hell to pay if Silna got excited about cell tissue and it turned out to be from someone’s spit.

Admittedly, though, the low gravity made it a lot easier to manoeuvre all that equipment into place than it would otherwise have been, and they made good progress. Around the second hour, Peglar (short, acrobatic, married to Bridgens the comms guy) arranged a work detail to help Silna prepare all the surfaces of the room, and things moved much faster after that, and conversation naturally turned to the drill, and the work ahead.

“So even if the newer ice nearer the sea is faster to cut through--” said Billy Orren, flicking out a plastic sheet which settled to the floor with all the speed of a single-ply tissue paper above a heating grate.

“Big if,” said Peglar, watching it very slowly drift downwards, “But on average, yeah.”

“--It’s still five klicks to go until it hits water!” finished Orren, passing the end of the sheet up to Esther, who was up a stepladder where she’d just affixed the rail for hanging it. “That’s months off.”

“Aye, and we’ve got five years worth of ice core samples to look at in the meantime,” Esther said. “Sure you won’t get too bored, Billy,” which prompted several people in the crowd to suggest other ways that Orren could occupy himself in the meantime. It got bawdy fast.

By the fourth hour, Silna had established her corner nook, with its benches and testing sites, sample fridge, microscope, steriliser, and a crate containing the really optimistic equipment like tanks and petri dishes. She had to keep readjusting the amount of force she had to use to do anything.

And all the while, she felt that constant low hum as the distant machine bored down into the ice. She lifted one of the full crates, marvelling that it felt like a box full of air, and her feet were in just the right position that the vibrations from that distant drill travelled up her body and made all the pyrex in the crate rattle audibly, until she set it down again.

Goodsir caught up to her at dinner time, his curly hair positively droopy as he joined her in the queue. By that point, Silna felt overstimulated and exhausted, all the excitement and effort catching up to her at once, and Harry looked like she felt. “All set up?” she asked.

“Somebody has already managed to concuss themselves on the ceiling,” he said, so woefully that it made her laugh.

Dinner turned into a party pretty quickly: when Commander Franklin arrived, he produced a huge chocolate sheet cake from somewhere in their stores. Silna could not figure out where or when they could have baked it, but she assumed it had to be somewhere on Erebus, because nobody would have had time today. It tasted, nostalgically, like the freezer aisle cakes that she remembered getting brought out at childhood birthday parties. Alcohol was banned on CSC missions, but people still managed to get pretty silly, which was probably because they were all tired, wired, and full of sugar - also like a kid’s birthday party. She even saw Fitzjames getting a smile out of Crozier, and she’d thought those two could barely stand each other.

Gore took a lot of photos, which must have been to send back to Earth. About an hour into the party, the screen on the wall lit up with a video call from Earth, showing the CSC control room full of cheering personnel, also eating cake, and a few veteran astronauts front and centre saying congratulations, how proud, great work, just the beginning, etcetera.

So it was a good night, but it had been a long day, and between the hectic afternoon, the noise of the party, and that constant drill vibration, she was going to bed with a headache.

But, when she turned in to her little room, she made sure to first record a video for her dad. And she told him she missed him, and she described the sight of Europa’s surface as the shuttle approached, bright as twilight under a water sky, the crags of unfathomably thick and ancient ice whose fissures turned out to be vast canyons as they got closer to the ground, cast with otherworldly shadows by the reflected light of Jupiter which loomed over the landscape. She told him about the vibration of the drill, and showed the camera around her little room, lingering on the qulliq, and shared her theory about the reason for the bunk swap, and Harry’s story about the concussion, which only supported her theory. She was grinning again by the time she finished; she could feel the ache in her cheeks and the way they must be creasing up her eyes, and her headache was not gone, but much less than it had been.

She hoped he could see how happy she was to be here. She told him she loved him. And then she added her video to the mail queue for Jopson or Bridgens or Gibson, one of the control room guys, to send out in the morning. Then she went to sleep.

She dreamed she was home again. She was walking over ice, solid and dry on top, that barely even creaked under her weight. She walked for a while, enjoying the stretch in her legs and the swing of her stride, and stopped at a place where the ice became very clear, thick and solid, showing the dark water underneath. And she walked further out, until she was standing on a blue pane suspending her above perfect blackness. And she watched the black water, her eyes searching for any movement in the deep stillness, until she saw some: a shape, moving, indistinct through the warping of the ice. And then it got bigger, and bigger, and almost as if in slow motion Silna realised that it was something vast, surfacing, coming right towards her, and even if she started running now she was too far out and it was too late.

She woke up with her heart in her throat.

She reached out with too much force and barked her knuckles on the wall, and the sudden pain was what woke her up all the way. She readjusted and hit the light panel, which came up soft and showed her her little concrete room.

She was fine. Everything was fine. But something was off, and it took her a while to figure out what it was. It was quiet, yes, but she could still isolate the hum of the generators, the hush of the air circulation, even muffled footsteps further down the corridor. Hurrying steps.

And then she realised what it was. The sound that was missing.

Half-rising, she opened her bedroom door just in time to see Crozier striding past, pulling on a jacket over his t-shirt and shorts, his hair standing up in tufts. He noticed her and paused, his face still set in fierce alarm.

She whispered, “The drill.”

Crozier’s face was grim enough to be an answer all its own, but he said, in an equally low voice, “Back to sleep, doctor.” And then he strode away, towards what she knew was the monitoring lab.

This couldn’t be happening. The drill wasn’t supposed to stop until someone on this crew stopped it. It was a nuclear-powered tunnel-boring machine that had been drilling independently since it was set off four years ago, and it was supposed to go until it hit seawater and not a moment sooner. Had someone stopped it somehow? How? Why would they?

She wasn’t a drill engineer, so she didn’t fucking know. She couldn’t do anything about it, so she went back to bed, and lay awake for an hour hearing the faint sounds of other people - drill people - getting up and scurrying down the corridor, until between one blink and the next she fell asleep again.

She woke up to the beeping of her comm, and when she tapped it she saw that there was an alert for an emergency assembly in the common room. It was in ten minutes. Outside her room she could hear doors slamming, and raised voices. She dressed hastily, and pushed her way out into the crowd. She saw tall Collins, a terrible expression on his face, and realised the person he was leaning on was Blanky. Half the crowd seemed to be in shock, and the other half looked as confused as she felt.

She ran into Harry Goodsir near the common room door, and he was one of the ones looking shocked, so she asked him, “What happened? I know the drill stopped, but…”

“It’s Orren,” Harry said, and that was all he got to say, as the crowd swept them into the room, where Commander Franklin was standing up the front, frown carved in his face like it was chiselled there, Crozier and Fitzjames and Gore all lined up beside him.

Billy Orren? All she could do was wonder what the hell could Billy Orren have had to do with the drill stopping in the middle of the night. Why would he do that? What could he have done? He was a PhD candidate who won a lottery to be picked for this mission - he had no more access to the drill than Silna did.

And then Franklin opened with, “It is my grave responsibility to inform you all of a death amongst our number,” and the whispers shot through the room around her like cracks across the surface of thin ice.

Chapter Text

NOW

The worst-kept secret of long-range, long-term, or interplanetary travel was that it was in many ways more comfortable than a trip to the moon, or those wretched jaunts between corporate stations in the asteroid belt. Most publicly-owned space agencies had hangups about letting their publicly-funded astronauts get absolutely wretched from bone and muscle atrophy, thus shortening their careers and forcing those space agencies to spend even more money training even more astronauts - so all the space stations and long-range ships had at least one ring section, where the centrifugal force mimicked gravity well enough for the astronauts to not come home utterly withered.

In other words, there might not be gravity in space, but spin your crew hard enough and their bodies wouldn’t really know the difference - give or take some weirdness from the coriolis forces. Thus, instead of ping-ponging around in zero-g, one could instead enjoy leisurely walks around the ring, proper sleep in a bed where you didn’t have to be strapped in for the night, and all the other accoutrements that made it a bit less like being hurtled through the void on a rocket, and more like a train ride in a sleeper cabin. If, that is, the train ride lasted several years, and you weren’t ever allowed off.

Fine, Sophia’s analogy failed her here. But thinking about it that way made her feel a bit more sane about going in literal circles all day.

The Lyra was a modest ship by interplanetary standards, with a relatively tiny crew, consisting of Commander Ross, Koveyook the flight engineer, a pilot named McClintock, a doctor named Cook, a linguist named Retter, and herself. The first few days involved some tricky work sling-shotting themselves around the Moon, and so Sophia spent as much of that time as possible being seen rather than heard, content to simply prove herself an obedient and unobtrusive presence.

But now they were out on the long part of the journey, where many months of spaceflight would stretch on between now and the rendezvous, so it was about time Sophia got down to work. The Lyra, barrel-shaped, laden with supplies, carrying equipment for an unknown disaster, nevertheless had ample space for all of them to keep out of one another’s way, and do the work they had each been assigned.

She had several terabytes of research to get through: letters and videos sent back by the Erebus crew that she’d persuaded some families to share with her, a few years’ worth of CSC reports on the Europa communication failures, and, of course, all those garbled transmissions. The reports were tedious and technical, and she had to brush up considerably on her knowledge of interplanetary communications just to understand how little they actually said.

The letters and videos took a lot more time, and it was hard to watch them with an impartial eye for detail, because they were simply too personal: a potent mix of intimate, charming, and ordinary that made her heart twist in her chest.

She had watched the messages from Uncle John enough times in the last year to know them almost word for word, but it was different watching them sequentially with videos from other crew members. Europa was a new focus for him, but he’d earned his knighthood by his work advancing the possibility of helium extraction on Jupiter, so he was a logical choice to lead the expedition: he had experience in keeping a large crew together for a voyage of that length. In his messages, he always seemed enthused about the crew’s myriad projects, many of which he was hearing about for the first time. But in every message of any significant length, he’d always wander back to the topic that preoccupied him the most: his recent ousting as the Governor General of Australia, and what he might still do to prove his detractors wrong. It had been a terrible time for him, Sophia knew, that poisoned his enjoyment of politics and sent him straight back to the space agency that had made his reputation. Sophia felt for him, always, and if she had her own private opinions about how he’d handled the matter, she kept them to herself.

It was only when Sophia lined these messages up with those of other crew members that she began to get a real sense of the expedition, and how removed Uncle John seemed from it. The experiments the crew talked about - in between private jokes, tender sentiments, and requests for updates about family members - were the work of years, sometimes decades. Even the astronauts her uncle had picked for the voyage, few of whom had ever actually been as far as Jupiter before, spoke of the project like they’d been keeping track of it all their lives. Fitzjames was third in command despite the fact that, as far as Sophia could discover, he’d never been further than Mars, and that as part of an armed force to protect Britain’s interests during the Tharsis/Orinoco merger and associated worker revolt. His videos to his foster brother were so ebullient; he talked about the Europa project like it was a childhood dream come true to be part of it.

(Funny, that she and Fitzjames had been on Mars at the same time for the same crisis, but she’d never met him. Ships passing in the night, she supposed.)

This voyage of the Erebus was the fourth crewed voyage of a project at least twenty years in the making, and all the crew, from the old-timers to the fresh-faced PhD candidates, were there to reap the benefits of all that had come before. Especially the Europa superdeep ice boring machine - or as she had always thought of it, Francis’ bloody great drill.

He and Ross had flown that drill all the way to Europa, as well as all the machines for building the habitat, on Erebus’s previous voyage. Four years, there and back, while she’d waited, and worked, and had her own brilliant career whose milestones he’d missed. And it wasn’t like she hated him for it - how could she? But she also had the terrible realisation, about two years in, watching his earnest face in a message that had taken 90 minutes to cross the distance to her at lightspeed, that she didn’t love him any more. All her fire had burned down to fondness, and then to the polite interest with which you might listen to a friend describe their hobbies. He hadn’t done anything wrong, and neither had she; all that space between them had simply starved her heart of oxygen. Even when he returned to Earth, returned to her, pulled her into his arms, it still hadn’t been enough to stir an ember back into flame.

She waited to tell him that it was over until he had had a month to enjoy being back on Earth, because it seemed the decent thing to do. But she hadn’t conceived that he might be surprised by it - that he could have spent those four years every bit as attached to her as he had been the day he left. How did he do that? She wished she knew.

So she didn’t have any messages from him for this voyage. It felt like a big gap in her research, a nasty reminder that she might, in fact, be a bit too close to this story for professional comfort. An actual stranger might have had more luck asking his sister or his best friend for copies of their messages from him. But because she was Sophie, who’d seen the inside of Charlotte Crozier’s kitchen on Christmas day, and covered for Ann Coulman and James Ross when they snuck away from a party for some privacy - because she had had the poor taste to have a change of heart, she got nowhere.

And the really fucking frustrating part of it was - she wanted to see them because she missed him. Because she wanted to see the way his eyes got very blue and bright when he was rambling on about, oh, ice density, or surface radiation, or how big you could make the equipment when you didn’t have to worry about it being torn apart under its own weight by Earth gravity. Because, all the mess aside, he’d been her friend for so long, and she resented the idea that she didn’t get to be worried about him, too.

Maybe one of the transmissions from Europa had been marked for her. They must have known that their messages weren’t getting through any more, right? How had it changed them? Were the messages they were getting from Earth equally garbled?

Sometimes, she listened to the Europa messages, trying to hear something, anything human in the sound - perhaps a snatch of a voice, like car radio passing out of range of a tower. But there was nothing human in it. If it was just static, that might have been tolerable, but it was stranger than that: sometimes it was a long, deep crackle, enough like a growl to convince her nervous system to raise all the fine hairs on her body; sometimes it was a high, almost mechanical squealing sound, reminiscent of a sound she’d once heard from two pieces of sea-ice grinding past one another, but hollower somehow, more massive, as unpleasant as nails on a blackboard.

She’d made the mistake of falling asleep while listening to one of the Europa transmissions only once on this voyage.

Sophia rarely remembered her dreams: something about her brain could just never hold onto them for more than a minute after waking, and after that she’d remember no more than a mood, or even just that she’d dreamed about something. But the nightmare she’d had then, of the whole ice crust of Europa opening like a set of jaws and crushing the habitat between its gigantic teeth, had stuck with her in her waking hours ever since she’d had it.

She hadn’t told anyone about that. She’d been upfront with everybody about her purpose and her publishing schedule. By now, she’d established a regular card game with Cook and Koveyook; she had had many interesting conversations with Retter about their experiences traveling through Europe and Asia, and through Retter she had found that McClintock could be drawn into talking about cross-country skiing or mountaineering. Sophia had even managed to make Ross smile a few times at team meals. They were all getting along perfectly well. There was no need to bring horrible dreams into it. The last thing this voyage needed was pessimism.

No, what she needed was useful research. And frankly, there was one great source sitting aboard this ship that she had not, until now, really made an effort to crack. But they were well on their way now, approaching that part of the voyage where a lot of them would take turns sleeping a great deal of the time away.

It was time for her to get an interview with the illustrious James Ross.

“Is it necessary?” he said, hand hovering on the rung of a ladder. He said it politely, even jovially, his face set in a slightly flustered smile; considerably friendlier than a few months ago, even if he did look as if he meant to flee at her first hesitation.

She matched him, letting a tinge of sheepishness colour her smile. “I’m afraid so. You are the mission commander, and know more about its logistics than anyone, so you are the most valuable interviewee aboard. That would be true even if you weren’t, well, who you are.” And she gestured vaguely at him as she said it, as if his importance were self-evident.

She watched the flattery register, and then work anyway. He opened his mouth, closed it, then sighed through his nose. He said, “I suppose it’s best to get it over with, isn’t it?”

“I think of it as establishing a baseline early in the voyage,” she said. “Would you prefer to do this in your lab, or in the crew lounge?”

He chose the crew lounge - thinking, no doubt, that there was a higher chance of them being interrupted there. In fact, McClintock and Retter were on their sleep shifts, Cook was taking her hour of resistance training, and Koveyook had just gotten a large packet of messages from his family twenty minutes ago - and Sophia knew him to be a diligent and enthusiastic correspondent. The crew lounge was large, comfortable, framed by many windows full of stars, and totally empty.

“Queensberry rules, is it?” Ross said, sounding mostly like he was joking.

“How hostile do you expect me to be, Commander?” Sophia said, her eyebrow raised. She set her handheld recorder on the table, where it slid against rotation, but fetched up gently against the raised lip of the table. Sophia folded herself into one of the soft couches bolted to the floor, and gestured for Ross to do likewise.

Ross put his hands up. “I expect you to be thorough, that’s all. After all, I believe you know more about me than most of your interview subjects.”

“You underestimate my background research,” Sophia said, smiling, “But you may be right in this instance.” Then she recited, “Sir James Clark Ross, OBE, PhD, FRS, FLS, FLAS, FBIS - gosh, you’re a fellow in a lot of societies - born in London, married to Ann Coulman, father of James Ross the second, Commander of this expedition. That’s the condensed version. Have I got the right man?”

“You do,” Ross said, dry.

“How is little James?” Sophia said. “It’ll be his first birthday soon, won’t it?”

A flash of warmth in Ross’ eyes, a curl at the corners of his mouth. Then he said, “Queensberry rules, Ms Cracroft.”

Sophia’s eyebrows rose, but she nodded. “Understood.” Family off-limits: a normal boundary to have. “Right to it, then. What is your theory about what happened to the Europa expedition?”

“Given Erebus’ current trajectory, we are working off the theory that, when the crew lost communication with Earth, they decided that the safety of the expedition would be best served by their leaving Europa ahead of schedule. Now, unfortunately we cannot know what the condition of the crew will be, or whether they experienced any difficulties apart from the communications blackout - we simply don’t have that data. However, satellite imagery provided to us by American and Chinese satellites around Ganymede, Enceladus, and Jupiter have given us enough information to track Erebus’ movements since it left orbit above Europa. Our calculations suggest the ship would not be able to make it to Earth right now - the planets are not positioned favourably, the distance will be too great - but the satellites captured images of the ship getting a gravity assist from Ganymede, and that might be enough to get them safely to the orbit of Mars, where they can be refuelled.”

“Do you worry about the Martian situation causing difficulty with that?” Sophia asked. “There are some aboard Erebus who were ranking Navy officers when Britain helped to pacify the cross-corporate strike.”

Ross waved a hand. “It won’t be a problem - there will likely be no interaction between Erebus and any of the corporate colonies. You’ll recall one of the reasons for the strikes was that the workers don’t have a way to leave the planet, and that situation hasn’t changed, so we don’t expect any hostile action. The board has assured me that the situation is stable and they have prioritised a refuelling mission that can meet with Erebus in orbit.”

Sophia nodded. “That will be reassuring to the families, Commander, thank you. So what, in your view, is the Lyra’s mission?”

“Mercy,” Ross said. “And investigation.”

“You fear they might not make it to Mars on their own?” Sophia said. It was certainly a thought that kept her up at night.

Ross’ voice was level, soothing. “As I said. We don’t know what difficulties they might have experienced. We have the power to render assistance if they need it, so render it we should. Fingers crossed, they won’t need our help at all, in which case we can ameliorate the communications problem and help transmit their messages back to Earth, which would be a great relief.”

“It certainly would,” Sophia said, smiling, and then asked, “Why didn’t you lead Erebus back to Europa on this last mission?”

Ross blinked at her for a moment, and then said, “I chose to retire instead.”

Sophia nodded; she knew this. “But you are here, now - out of retirement.”

“I wanted to get married,” Ross said. There was a warning note in his voice.

“Yes,” said Sophia, “It’s a very good reason. You commanded two Erebus missions, didn’t you? And you served on the first, before Commander Parry’s retirement. How many years in space is that, cumulatively?”

“Twelve,” Ross said, “On the Erebus missions alone.”

“Twelve years of your life on missions to Europa,” Sophia said, softly. “The project must mean a great deal to you.”

“Of course it does. It’s our best hope for finding extraterrestrial life. It’s been decades in the making - our highest ambitions of what the facility could be are realised. It’s been an absolute privilege to be a part of it.” And she saw the truth of it on his face: something earnest and longing that she knew from the faces of - well, many scientists she had known. Part of something greater than themselves. Worth leaving anything else behind.

“And yet,” Sophia said, gently, “at the culmination of all that work, you chose to step away, and leave another to take the credit for discovering life on another planet.”

A little impatience on Ross’ face. “It isn’t about credit.”

“It isn’t?” Sophia said. “Is your reputation not founded upon the work you’ve done for this project?”

Ross ignored that. “And we haven’t found evidence of life on Europa yet - unless the current expedition has done so, and if they have, they deserve all credit for that.”

“It’s a very large crew, isn’t it?” Sophia said. “Did you hear any concerns raised about that?”

“Yes, of course,” Ross said. “It’s the largest crew ever taken beyond the asteroid belt. The expense alone has been astronomical: simply getting that many people and all their supplies into orbit to rendezvous with Erebus has made it the most expensive part of the project, and then, of course, Erebus herself has had to be reconfigured and expanded to fit so many, and there was the cost of hauling all the equipment to Europa - it just goes on and on. It was a lot of taxpayer money coming from multiple nations. But of course, the tradeoff is the expected return on those nations’ investment: Europa is an enormous asset.”

A jewel in the crown, estimated at tens of trillions of pounds in value. It would help to include the exact figure when she wrote this up. “Was expense the only worry?”

Ross hesitated. “No,” he conceded. “There were also concerns--” (he had a masterful grasp of the passive voice, she thought) “that such a large contingent of civilians would have difficulty coping on such a long and physically demanding expedition. It was projected to be a five-year mission. But that is why they were all rigorously tested for physical and psychological fitness, compatibility, all the requisites. We did have a number of people who had to drop out of the training module for health reasons. The rest passed.”

We, she noticed. Even though, while the mission was getting ready, he had been retired in domestic bliss. “But it can still take an enormous toll, can’t it? Five years of space travel - the isolation, the knowledge that you’re so far from home?”

There was a touch of gravel in Ross’ voice when he said, “Yes, of course it can. People miss home a great deal. That’s inevitable.”

She nodded. “Was there any concern about the fitness of command for this mission?”

He raised his eyebrows, like he hadn’t expected her to address that. But to his credit, he thought about it, and then said, “I heard some criticism of the choice to put Sir John Franklin in command - because of his age, and the… gap in his career in space. But I will say, I thought that criticism was unfounded. He passed the same fitness tests as everyone else, and his record--” she failed to hide a wince; he saw it. “His record as an astronaut is unblemished. He was perfectly qualified for the job.”

“Why was he chosen over a veteran of the project?” Sophia said. “He wasn’t chosen as project leader until the Europa Simulation was concluded. A bit of an outsider choice, wasn’t he?” And the name she wasn’t saying was the name that Ross also wasn’t saying, burning a hole on her tongue. It was like playing chicken, or a blinking contest: first to say ‘Francis’ loses.

Ross said, carefully, “I was not involved in the process of choosing the commander of the last mission, but I know that other prospective candidates turned it down; they weren’t considered unfit, but considered themselves less qualified for the role than Sir John.”

Bullshit, she thought. But God, maybe it wasn’t - maybe Francis really had felt unfit for it. Or else it was such a horrible job that he didn’t want it. What had he said to Ross in private? What might he have said to her if--

She said, “Did you have any concerns about the other astronauts’ fitness?”

A muscle twitched in his jaw. He flatly said, “No.”

“Even though several of the command crew have never been further than Mars?” she said. “Captain Fitzjames, for example?”

Surprise, chagrin, annoyance: she watched them war on his face, and looked back as if butter wouldn’t melt in her mouth.

Eventually, he leaned closer to the tape and said evenly, “It was necessary to expand the roster of astronauts in the command crew from that of previous missions, in order to manage the large number of participants. That required bringing in new people. All the command crew are highly qualified, proven astronauts. I have full confidence that every reasonable measure was taken to reduce the possibility of human error causing problems on this mission. Whatever caused the communications issues, or any other problem that this mission has faced, I am sure the crew will have done everything in their power to ameliorate it.”

“So you have every confidence in the crew?”

“Every confidence.”

“And you were happy to step away from this project?”

“As I said.”

“So why are you here now?” she said. “You walked away for a damn good reason. You got everything you could wish for. Why leave it behind now?”

He stared at her for a long time. “What kind of-- Why did you?”

“Commander, I’m not--”

“You’re here for your uncle, aren’t you?” he said. “Unless I’ve utterly misjudged you. My son’s godfather is on that crew, and I know you know it. Others besides who I have known for twenty years or more. Why else would I be here?”

She noticed herself biting the inside of her cheek; made herself stop. “You’re worried about them.”

“Of course I am.”

“You don’t think it’s just a communications issue, do you? There’s something else.”

“That’s speculation.”

“You’ve got to be basing it on something.”

His mouth was a thin line. “The satellites above Europa stopped sending coherent images two weeks after they landed and twelve days after their last intelligible transmission. Their last image was of a tender drone that had been sent up from the surface.”

“Okay?” She’d already written about this, in her first feature about this mission. People on Earth had read all about it by now.

“But they’re not the only satellites in operation around Jupiter - that’s how we know Erebus is coming back, from other nations’ satellites. Why couldn’t they find a way to use those satellites to transmit something? Yes, there’s all kinds of natural interference that might scramble a radio signal, but how does it persist for all this time, when nothing like it has been noticed on all prior expeditions?” He was gesturing, now, his usual reserved body language loosening, like a dam cracking. “The alignment of planets hasn’t changed it, differing rates of solar activity haven’t changed it, there have been no recorded strange activity on Jupiter that might explain it. It would be one thing if the transmissions had simply stopped, but they haven’t - Erebus is still transmitting, and it’s still just noise to us. What could have scrambled communications so completely, and for so long?”

“Do you-” she said, too quiet. She coughed and tried again. “Do you have any theories?”

“No. All I know is what I don’t know. I cannot build a theory off of no data.”

She let that hang for a moment, and said, “Do you have any further comments, Commander?”

“No,” he said.

She picked up the recorder, paused just in case, but he didn’t say anything. She clicked the stop button.

Ross’ throat clicked. “Now that we’re off the record: what was that?”

“Like I said,” Sophia said, “A good baseline. Thank you.”

THEN

Commander Franklin’s briefing was so formal it communicated almost nothing, aside from this: the drill had stopped some time in the night. They didn’t know why. Early in the morning, Crozier had led a bunch of engineers and drill crew to the rig site for a visual inspection. And then something had happened that ended up with Billy Orren falling down the borehole they’d cut in the ice, presumably all the way to the bottom where the machine itself sat, inert. Then he gave them their instructions for the day. Option 1: seek counseling and take the day off. Option 2: return to your lab and resume work under manager supervision.

And then he said some things about what a loss it was, and a tragedy, and of course all participant excursions to the drill rig would be suspended pending completion of the command staff’s investigation into the incident, and he believed in their fortitude and team spirit and at that point it just turned to so much noise in Silna’s ears. In the hush of the crowd, she caught the sound of someone crying.

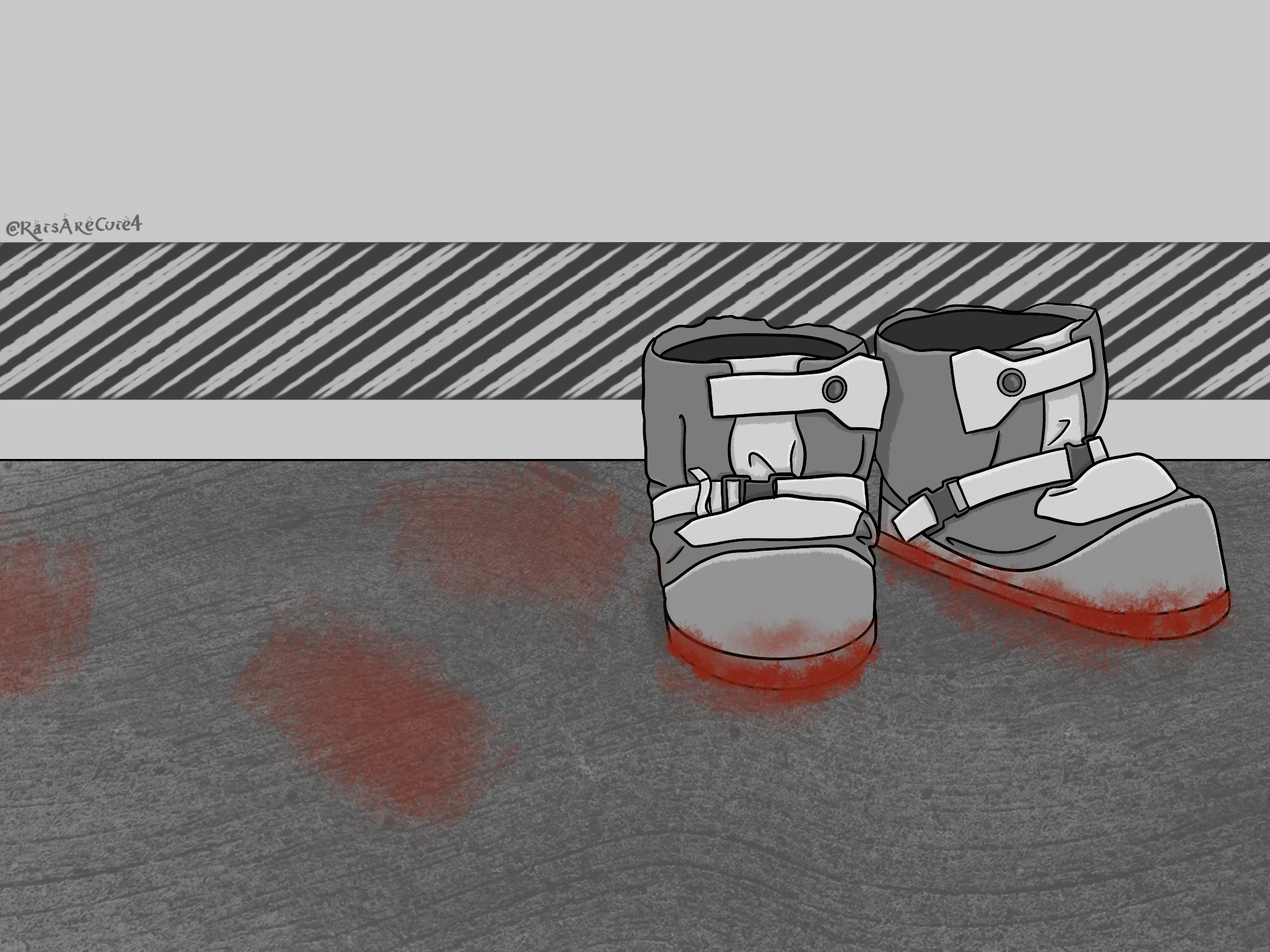

Goddamn, what a way to die - falling, what, twenty kilometers? More? Right onto that unmoving, nuclear-powered drill. Surely that would be enough to kill him even at this low gravity, right? Was his suit intact? If it wasn’t, that was its own death sentence - as good as dipping the guy in liquid nitrogen to expose him to the temperatures outside. She hoped that was what had happened - that his suit had gotten torn, and frozen him in an instant.

She remembered being a little kid, hearing the news about some guy - the kind of elder she saw around town, but never talked to - who got drunk, walked out into the night, and went straight through some thin ice. She remembered hearing about it, and all the adults said, what a damn shame. What a waste. Poor soul. At least it was quick.

Quick didn’t mean instant - she learned that later. But better that than a long fall, and somehow surviving it only to realise there was no way back up from the bottom of that pit.

As soon as Franklin stopped talking, Silna heard her own thoughts echoed in the muttering around her. It sounded ghoulish out loud, but it wasn’t like she was any better. Horror and curiosity was a potent mix, and everyone wanted to know what the hell had happened.

So a weird pall hung over the first full day’s work in the ice core lab. Blanky stood at the top of the room when they all filed in, scrolling through his tablet with a preoccupied look on his face. The conversation was a low buzz compared to the cheerful din of the day before, and Silna pulled on her PPE with an uneasy feeling.

Finally, Blanky raised his voice. “Right! Settle.” The low buzz died entirely, and Silna joined the rest in gathering in the largest empty patch of floor. Blanky said, “This is all of us for today - there’s a few who are taking time for counseling, and if you think you might need some, bloody well take it. If you think you’re alright and realise you’re not halfway through the day, come and tell me. But I know some of us feel better with work to take our minds off it, so: we’ll start on the ice core samples today, as planned.” He raked his hand through his shaggy grey hair. “I know it’s a shock. We all knew Billy. Captain Crozier is leading the investigation, and as Commander Franklin said, there’ll be no participants allowed up to the rig until we’re satisfied it won’t happen again. Are there any questions--” A few hands shot up-- “about how we’re proceeding today?”

The hands sank. There was a little shuffling in the crowd, but no more hands were raised.

“Okay,” Blanky said briskly, “Teams for today will be as follows…”

Silna was rostered on to the ice core melting system with Esther Blanky and Tom Hartnell. They’d set it up and plugged it in to do its software installations yesterday, but now they needed to actually calibrate the thing and do a few tests with dummy ice cores they’d created from their own system’s water. While they were doing that, other crews would be performing similar calibrations, or remotely piloting drones to go and collect the ice core samples from the massive hangar next to the drill rig where they’d been accumulating for the last four years.

For the first hour, the three of them exchanged barely a word that wasn’t directly related to the work in front of them. Silna wasn’t a big talker, but Esther was, usually; you could pick her out of a crowd by the roar of her laugh. Hartnell, too, was usually chatty. Not today.

Silna didn’t want to pry; she knew they were both drill crew, but didn’t know if everyone had been woken up for the site visit, or if they were just a tight-knit enough group to be feeling it. But, about twenty minutes into waiting for the first dummy sample to melt, Esther heaved a big sigh and said, “Oh, lord. It’s just shit, isn’t it?”

Hartnell nodded, and then looked awkwardly at Silna like he was waiting for her to say something. Silna, who didn’t know what the hell to say, kept silent, but pressed her shoulder to Esther’s as she passed, and got a squeeze to the shoulder in return. She shared a commiserating glance with Hartnell, and they resumed their work.

It was only on the lunch break - still subdued, if not as funereal as the morning - when Silna finally heard about it. It wasn’t from Esther, though - it was from Charles Des Voeux, who was telling the people at the table next to hers.

“Yeah, alright? Yeah, I saw it. It was fucking awful. We were all on the walkway around the pit, and it’s a big hole and all, it’s like a train tunnel, but it’s not like we were all just standing about gawking - there was shit to do, you know? But Orren was on the catwalk above it. There was this little tremor, like, not even hard, just like the ice was cracking a bit, but not enough to make anyone lose their balance. I didn’t see him go over, but we all heard Collins yelling on the open frequency, and it was a slow fall, but - well, Christ. It was like he was falling almost sideways, towards the middle, kind of spinning. I saw him slam into that big suspension cable, and his suit vented, and I suppose that was it, you know? Must have frozen solid. Collins was going spare; I had to stop him from doing something stupid, like diving after him - like that would have done any good. They looked at Orren’s biometrics, so they know exactly when his heart stopped, and it was right then. He was already dead. Suppose he’s at the bottom by now. Twenty-odd klicks down. Poor kid.”

There was a moment of silence, while Silna pictured the whole horrible scene, and looked uneasily at Hartnell, who was staring down at his food, just kind of hovering his spoon over it with a blank expression.

At Des Voeux’s table, somebody piped up, “But if he’s on the drill now, what happens when it turns back on?”

And even Silna had to look around at that, appalled, to see Des Voeux’s face looking like she felt. “Jesus, Evans,” he said. “I’m sure they’re considering it, alright? Christ, that’s me done with lunch.”

Yeah, Silna was feeling that way too. She got up, pausing to awkwardly pat Hartnell on the shoulder, bussed her tray and headed back to the lab.

She checked her messages as she walked, but there was nothing since this morning’s alert. Dad hadn’t sent anything back yet. She was wondering how she’d tell him about this tonight - though, of course, she couldn’t say who it was until command had had a chance to inform the family, so, fuck, maybe she wouldn’t. She wanted a video of home. She wanted to see aunties and kids and animals.

She could feel it starting to hit her - she hadn’t known Orren well, but she’d still shared a ship with him for two years. Everything was starting to feel a little unreal. She walked past the corridor that led to the command crew’s offices, and heard raised voices for a moment until there was the snick of a door sliding shut. She passed the stairway up to the comms room, and Jopson clattered down the stairway and hurried past her with a tablet in his hand.

The investigation, she guessed. She hurried on, until she hit the soothing cold of the ice core lab.