Chapter 1: one

Chapter Text

“You hold up that jar like I’d ever say no. Of course I want more.”

Lan Zhan settled next to Wei Ying, resting yet another jug of Emperor’s Smile in his open palm. Technically, since the Cloud Recesses already forbade alcohol, it had no expressed rule against drinking alcohol in bed—an oversight which Wei Ying relished.

“You sure you don’t want any?” Wei Ying grinned as he pulled off the stopper and tossed it aside. Lan Zhan shook his head and paused a moment. The corner of his mouth flickered.

“It would be unseemly to steal more chickens as Chief Cultivator,” he replied.

It was another winter tucked in the mountains of Gusu, another evening snowstorm piling at the sills of the Jingshi. Wei Ying poured another sip into his mouth and then pressed that mouth to Lan Zhan’s shoulder.

“You really can’t let that go, can you,” he smiled into his crisp white zong yi.

“Every day since you told me I crumble in humiliation.”

“Dramatic,” Wei Ying said. He tucked a strand of hair behind Lan Zhan’s ear and darted another kiss at his neck. “I’ve done far more embarrassing things drunk.”

“Mm, the eloquent love note from Yiling Laozu . I remember it well.”

Wei Ying yelped and twisted around, scrambling for a pillow to smack Lan Zhan. But the latter caught his wrist midair, and then entwined his hand, and then pulled Wei Ying’s laughter against his own.

It’d only been a few days since Wei Ying crunched past the Cloud Recesses gate. At the first frost, he nestled back into the Jingshi’s warmth, tales of adventure fresh on his mouth and a dashing new shoulder scar proudly displayed. During his travels, he made good on his promise to steal the Chief Cultivator—and of course swung back to Gusu for his first Qixi as a married man—but it had still been months since he last stayed with Lan Zhan.

And now, Lan Zhan welcomed his husband with a mix of tender kisses and absolutely humiliating recollections.

“How did it go, again” Lan Zhan mused into Wei Ying’s jaw, tracing through memories of the previous year. “I’m drunk, I miss you, get on a boat and visit me in Lanling?”

“No, it’s so embarrassing—”

“Or was it: Lan Zhan, I simply cannot stop rereading your letters, I’m consumed with lust and want you here this instant.”

Wei Ying trailed his fingers along Lan Zhan’s waist. “Lan Zhan, you act like you’re not a bigger flirt than I am,” he grinned, voice light.

What?

“I do not flirt,” Lan Zhan said, pulling back slightly.

“You don’t flirt— Lan Zhan, you’re kidding me.” Wei Ying tossed an arm to the side for emphasis. He noted the tiniest curve of Lan Zhan’s mouth.

“I do not. I am always straightforward.”

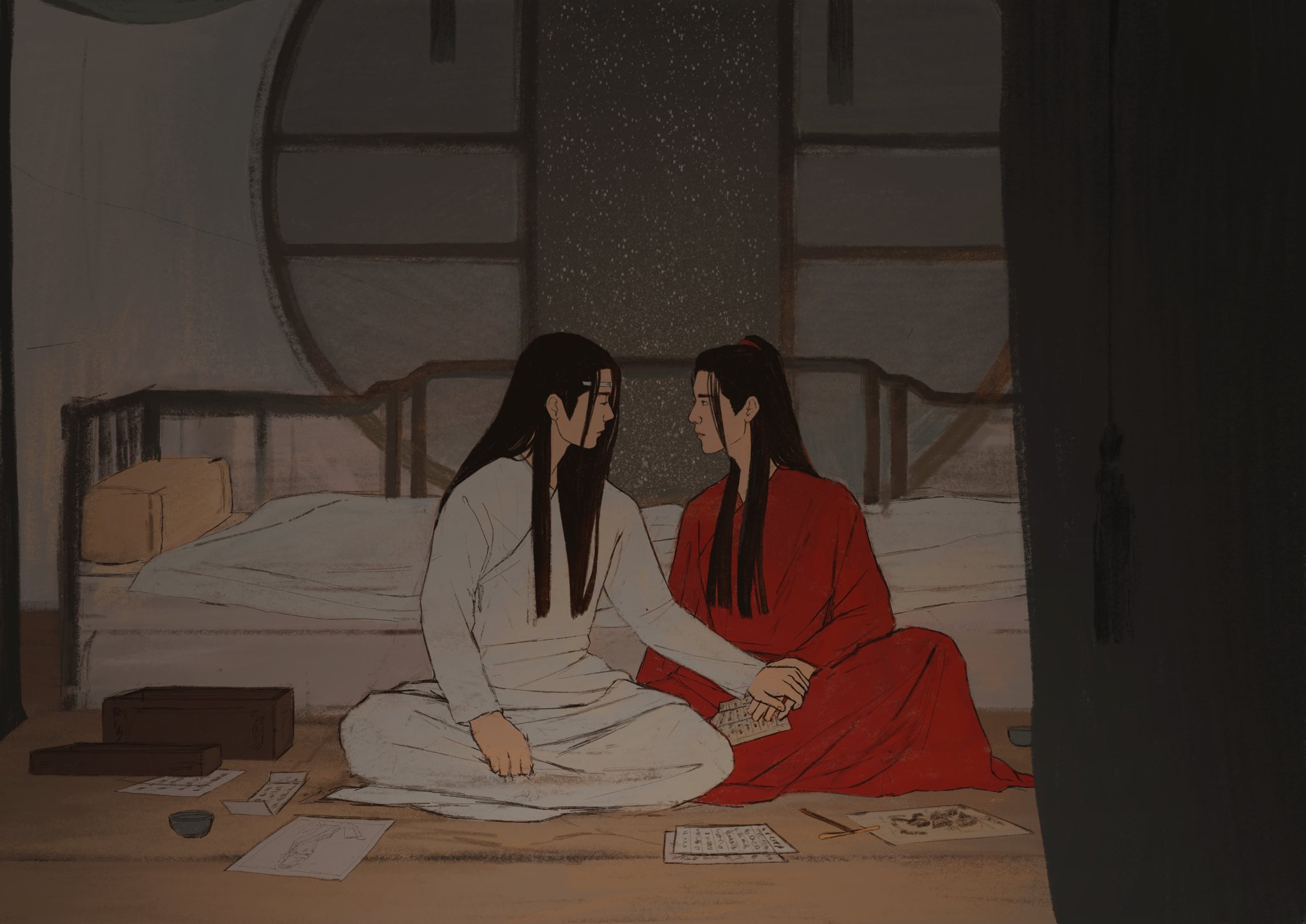

“Oh, my God,” sighed Wei Ying. He untangled himself from Lan Zhan and dropped to the floor to reach under the bed. He fumbled, marveling at the lack of dust, until his hand hit soft leather. Aha.

He pulled out his satchel and, sitting cross-legged on the floor, rifled through a veritable collection of love letters from the esteemed Hanguang Jun. That same Hanguang Jun dipped beside him as he unfolded page after page. Finally, he settled on a sheet nearly torn at the creases.

“Here— I nod and say you’re well, for how could I admit more? It would be brash as describing the river and the heaving sea, and how their meeting turns to flood the fields,” he narrated. “I’m sorry, Lan Zhan, that’s flirtatious.”

Lan Zhan drifted his gaze to the side with a shrug. Wei Ying kept unfolding.

“And don’t even get me started on—”

He was so annoying. Lan Zhan kissed him.

“You saved them all,” he said when they parted, looking at the heap of paper.

“Of course,” said Wei Ying. He raised his brow. “Did you not save mine?”

“Ridiculous.” Lan Zhan blessed his husband with both an eye roll and a smile. He moved to a bookshelf under the window and returned with a dark wooden box, willow branches carved into its lid. He centered it on the floor before them.

“So sentimental,” Wei Ying teased. “You should let me read your diary next.”

Lan Zhan blessed Wei Ying yet again, this time with a light shove to the shoulder. He then lifted the lid and set it down. Inside was a neat stack of letters and other things—a tassel here, a carving there.

“This!” Wei Ying exclaimed, pulling out a sheet of paper with faded ink and yellowed edges. A portrait, saved over twenty years. He lifted it beside Lan Zhan’s face.

“I must look so old in comparison,” Lan Zhan said.

“No. Exactly the same,” Wei Ying replied softly. He studied the likeness. His linework had changed over the past two decades. It was heavier, now, and more immediate, so unlike the fragile marks in his schooldays.

“I can’t believe I added a flower in your hair,” Wei YIng continued with a little laugh. “I was such a disaster.” He traced the lines with his fingertip. “I liked you so much.”

“That drawing held a beautiful moment until you expertly ruined it,” mused Lan Zhan. He combed his fingers through Wei Yings ribbon and bit back a smile at the memory.

“Like I said, I was a disaster,” Wei Ying agreed. He recalled Nie Huaisang’s murdered erotica. “It was worth it, though. I got Hanguang Jun to say piss off.”

Wei Ying rested his head against Lan Zhan’s shoulder and continued sorting through the box. Folded together were the short notes he wrote before meeting on the Gusu mountainside. And oh, underneath was his very first letter—from two years ago!—its blot of chili oil now blooming almost to the paper’s edge. His chest ached when he caught a glimpse of the words yours, Wei Ying underneath a nervous spread of ink.

“Ah, and this one,” he said, pulling out a crisp sheet he sent earlier this year. “Apologies again for the bad poetics. I was...not sober.”

Lan Zhan raised a brow and undid the letter, skimming a particularly lewd passage toward the end. He glanced back to meet Wei Ying’s eyes.

“Me, more flirtatious than you,” he echoed with a twist at his lips. “The audacity.”

Wei Ying craned his neck to reread his own words and grinned.

“Hey, I was being very straightforward there! I straightforwardly described, in extremely straightforward detail, that I thoroughly wanted to—”

Lan Zhan caught his sentence with another kiss, deeper this time, twining his fingers at the roots of his hair. Wei Ying pulled away just long enough to get the last word.

“Lan Zhan,” he breathed, “it served you right for all the good poetry you wrote me.”

By this point in their marriage, the word shameless was heartily implied in every other sentence. And so Lan Zhan just smiled and held Wei Ying close. The wind outside swept hard. A drift snagged in the doorway, rustling their canopy of heating talismans and flickering a candle out. Lan Zhan shot the flame back with his fingertip.

Wei Ying leaned upright and studied the pile before them once again, smoothing his hands across the box lid’s carving. He knew Lan Zhan rarely threw things away, but he didn’t realize how carefully he kept mementos, how earnestly. Wei Ying looked at him, admiring the spill of hair over his shoulders and his profile edged in candlelight. He smiled at Lan Zhan and reached for the box. As he rummaged deeper, his hands closed around a little wooden rod with a propeller top. He pulled it out and held it in his palm.

“Sizhui’s,” said Lan Zhan.

“I remember,” said Wei Ying. “You bought it for him in Yiling.”

Underneath the toy was another drawing. Its strokes were broad and clumsy framed with smudging fingertips, but the page itself was carefully preserved. Wei Ying studied the shapes and then slowly met Lan Zhan’s gaze.

“These are lotus pods,” he said.

“Also Sizhui’s,” Lan Zhan replied, his voice catching on the name.

“But where would he have seen—” Wei Ying started, and then fell silent at the memory of his crop at the Burial Mounds. The plants twisting up through murky sludge, Sizhui’s fist barely large enough to grasp a stem. Tossing seeds way high up in the air and watching Sizhui fail and fail again to catch them in his mouth, laughing all the while. Wei Ying’s eyes stung. Lan Zhan smoothed his hair and then pulled him closer.

“He didn’t remember what they were when I asked him,” Lan Zhan whispered. “He said he liked to eat them. He asked if I had any to give.”

Wei Ying pressed his mouth together and nodded and glanced to the side. He rested his hand on Lan Zhan’s knee and gripped the fabric there. It was silent for a long while.

“Well, I can bring him some if I ever stop by Yunmeng, then,” he said at last, after he was sure his voice would keep steady. Lan Zhan brushed a light kiss to his temple. Wei Ying turned back to the box.

“Ah, whet else is in here?” he said, his voice a little too bright. “Locks of hair? My first copy of the sect rules?”

He rubbed his hands across his arms and tucked closer to Lan Zhan. He met his gaze and then looked away, chewing on the edge of his lip. He messed with the ties of his zhong yi. He messed with the edges of his hair. Lan Zhan was quiet. Wei Ying studied the ground.

His arms remembered hauling Sizhui up the mountain, scratched from brush and gummed with sweat. Now they held Lan Zhan, pressing the lattice of his back through the cloth of his shirt. Lan Zhan’s hands remembered the bite of guqin strings, fingerprints etched with notes of Inquiry. Now they held Wei Ying, one smoothing his temple and the other twining his fingers. Sixteen years weighed around them, then, folding from their heads and pooling at the floor. Wei Ying took a breath.

“I’m glad a-Yuan couldn’t remember, he whispered finally into Lan Zhan’s shoulder. “It would’ve been too hard.”

Some snow rushed through the doorway crack and sank to water in the heat. Lan Zhan thought of the bedtime stories he once told Sizhui, about dashing swordfights under moonlight and mischievous adventuring papermen. He swallowed hard and got up to make some tea. He returned with two steaming cups to find another letter in Wei Ying’s palms. When he knelt closer and held the paper, limp and warm, his fingers froze.

Wei Ying glanced up to notice hazy eyes. He smoothed a lock of hair from Lan Zhan’s face. Lan Zhan opened his mouth and then closed it. He gave a gentle nod. Wei Ying took the letter from his hands and undid it, careful not to break it at its folds. The writing was faded but neat, and when he read the topmost name written in Lan Zhan’s hand, the softest ache grew to bloom across his chest.

“My A-Yuan,”

Wei Ying began aloud.

Chapter 2: two

Chapter Text

My A-Yuan,

There is a song I strove to keep secret, allowing its melody only after your lullabies. Yet last evening you awoke in its midst, and heard enough notes to inquire its meaning. After a moment I told you it was my own lullaby, and your small face nodded with sleepiness, and I carried you back to bed.

I’ve asked you of your memories and your little voice tells me only of clouds. You have a fresh start here. I should be grateful, I am grateful—yet I still tend hidden pain at your lack of memory. For beyond where your memory falters, there was another man who once raised you. And last night, without even knowing, you asked of him.

As I write this, you are asleep in the corner, breathing softly under the window. You are so young. When you read this, you will be old enough to know your full story. And in the meantime, while I hold his name close, I fold his memory into our everyday.

In the mornings you help me tie my ribbon on. Soon I will center one on your own forehead and smooth your hair before your studies. Our Lan sect lives by a weighty slab of rules. In my youth I cherished each one, searing them into my actions and mind. As you grow you will also learn the rules. And when you come home from lectures, I will unravel their teachings. For in my youth I thought I understood black and white. But then, in my youth, I met the man who raised you.

Our Lan Sect Rules:

One must accumulate merits and good virtues.

(He did, in spite of his early easy ways—his joy never stemmed from cruelty, his kindness never saw fatigue.)

Stop evil, spread good. Give more, take less.

(A promise he made on our mountainside, sent up with a lantern and sealed with clasped hands.)

Be loyal, filial, amicable, and respectful.

(His loyalty and respect cherished those deserving.)

Pity the orphans and sympathize with the widows.

(He saved them from bloodshed.)

Help others in times of need. Save others in times of danger.

(He shielded the innocent, nurtured life after wartime. He grew life from a mountain of deadened soil.)

Treat others’ gain as your own gain. See others’ loss as your own loss.

(We eased departed souls after slaughter, a duet against the silent trees.)

Feel sorrow for being evil. Be happy for helping others.

(He smiled at those who resented him. In the rain I worried for him until I cried, in the rain I let him pass.)

Change for the better so you can change others with you.

(And he changed me for the better, and I bear the scars to prove it.)

A good person would be respected by everyone, blessed by nature, and good fortune would come to him.

(How tightly I once clung to such a promise.)

A-Yuan, I don’t know how to be a father. I plant you in rabbit patches and feed you carrots and I’ve never found words to explain why you cannot climb my back. I sit you in my lap and guide your hands over guqin strings and I have no words to explain why I sometimes cry. I don’t know how to explain why I went away for a little while. And if you one day begin to recall fragments of your past, I fear I won’t be able to explain it without my voice breaking.

And so I write you this letter, to press into your hand on the day you ask.

I found you in the Burial Mounds, feverish and crying. I carried you home. I dressed you in white and took you as my son. I changed your name to hope, to longing. I named you for him.

As you grow, you will doubtless hear his name from cutting, sneering mouths. Yiling Laozu. Wei Wuxian.

But you may hear his name softer, under breath, from my own voice.

Wei Ying.

All I can do is teach you well, teach you the best I can, teach you with the care of his memory. For in his lifetime, I held him closer than any other. Every day I miss him. He was my confidant. He was the mirror of my soul. Still, he is.

And he loved you, his son, Wen Yuan.

And Lan Yuan, my son, I love you.

They leaned against each other, the letter open over both their knees. Wei Ying clasped Lan Zhan’s hand and felt its warmth and wove his fingers in between. They looked ahead. The doors were pulled closed but patterns of snowfall ghosted through the windows, falling faster and piling at the seam of the Jingshi and the deck.

Incense smoke mixed with steam rising from the tea. It curled against the ceiling and brimmed the room with scents, herbs and flowers sheltered from the growing snow. Wei Ying held Lan Zhan and pressed closed eyes to his shoulder. The wind outside picked up and a dust of brown leaves skimmed under the door. Lan Zhan blinked and rose to the threshold.

“You don’t have to clean it now,” Wei Ying said softly.

Lan Zhan stopped but did not turn around. He folded his arms behind him and stood there for awhile, his bare feet sinking in the carpet. Wei Ying gently centered Sizhui’s letter back within the box, next to another saved childhood toy—a little flute, carved from bamboo. He steadied his breath and went to Lan Zhan and draped his hand across his back. The muscles loosed against his palm. A drift of snow hit the windowsill and melted underneath. Some water stained the wall.

“I still raised him with you,” Lan Zhan said at last, and the floor cut from Wei Ying’s soles. And he pulled Lan Zhan to him until no space was left.

They stayed there for long minutes, sixteen years around them still but easing at the edges. WIth his face pressed to Lan Zhan’s chest, Wei Ying thought of the clearing on the mountain. Of chasing around a little boy. Of a sisterly voice chiding them both— clean up, you two, and get ready for dinner! Of meeting a-Yuan’s eyes and bursting into a smile and running even more, caking as much dirt as possible onto grubby hands. And Wei Ying would get tired but wouldn’t show it, because how could he lose a race to a kid? No, he’d tumble into the ground just as well, and then after dinner he’d curl in a window with a-Yuan on his knee. They’d watch evening soak up twining branches and a-Yuan would ask for a story, and when Wei Ying ran out of made-up spirits and dashing battles, he’d tell a-Yuan about a man who played guqin.

“Wei Ying,” Lan Zhan whispered, breaking him out of memories. He brushed his thumb across his cheek and it was wet. Wei Ying huffed a small laugh.

“Ah—you, too,” he said, drawing a finger along Lan Zhan’s own stained face. Lan Zhan hugged him tighter.

Wei Ying laughed again and sniffled, and then glanced across the room at the writing desk, still stacked with sheets from talisman-drawing and chief-cultivating. He pressed a kiss to Lan Zhan and then pulled him over by the wrist and plopped down. He rifled through paper for a clean piece and smoothed it out before him.

Wei Ying handed Lan Zhan some ink to grind. Lan Zhan raised a questioning brow.

“I remembered some urgent correspondence,” Wei Ying replied. He pulled Lan Zhan closer and tucked beneath his arm as he wet his brush.

Lan Zhan rested his head against his husband’s and watched his brush dip into the page. Wei Ying’s writing was usually frantic, but here he held his brush carefully, moved it slowly. Lan Zhan watched the opening characters unfold. And when they formed a name, he felt his breath fall once again.

My a-Yuan,

I would like to tell you about your father.

I am nowhere near as poetic as he is, so you’ll surely forgive my clumsy attempts at description. The story of your past is intertwined with his: he took you home, and held you, and gave you the Lan name. You know this, sure as you tie the ribbon at your forehead each morning. But I would like to tell you about a time before then.

Your father has read more books than anyone I know. At your age, he wore his hair loose around his face and carried the same yaopei you carry now. His smiles were very rare (really!) and I strove daily to earn them. When he fought me—which was often at first, and always great fun—I swear not a speck of dirt ever touched his robes. Even back then, his calligraphy was the best in Gusu. And when he wrote poems as I copied the Lan sect rules, he drew little pictures in the margins of the pages.

Your father has a good singing voice, which he never shares even though I tell him to. I’m sure you’ve heard him hum little tunes that later shift to guqin notes. THe melody he repeats the most—he composed it, did you know? He sang it to me in the belly of a cave, and his voice was the last thing I heard before waking up in sunny daytime. We got into trouble as children—more trouble than you’ve ever been in, I’m sure. But if you must get into trouble, there is no one better than Hanguang Jun to have by your side.

Your father’s well-chosen words have never rung false. Really, they haven’t! I even asked him once if he ever tasted Emperor’s Smile, and much to my dismay, he answered an all-too-truthful no. Perhaps when you try your first drink—you’re mine, too, after all—we will convince him to test a sip. Only a sip, though. He might otherwise wax poetic about rabbits. He really likes them, after all. He’s told me so himself.

If you dig back deep in your memories, you will recall a time when your father wore blue. You held his leg in the middle of the street until I came and scooped you up, and together we looked at trinkets. You called him “Brother Rich”, then, which was a deserved title after he cleaned out an entire stand to shower you in gifts. You climbed in his lap and he held you, and I watched you both, and an ache filled my chest. You drew smiles from him, a-Yuan, so quickly. He bounced you on his knee and gazed at you and adored you, even as I carried you back to our home on the big mountain. He loved you, even then. And under the weight of the world—even then, I began loving him.

An ink stain hit the paper as Lan Zhan tipped Wei Ying to face him.

“Ah, I was being so careful,” Wei Ying lamented at the spatter. He smiled, though, and cupped the side of Lan Zhan’s face, thumbing away more haziness at his eyes. A candle flickered close to its base. The wind outside softened to a lowered hum. And inside, the Jingshi swelled with warmth.

“Lan Zhan,” Wei Ying whispered. And because no other words found their way to his mouth, he kissed him—his cheek, his temple, his jaw, his forehead. And Lan Zhan chased his lips with his own, humming into the touch with notes from long ago.

“Lan Zhan,” Wei Ying said again, pulling away just enough to speak. He looked at the box by the bed, marveling at the years it held inside. One day letters would stack to its brim, and one day they’d kneel older bones to the floor, unfolding and reading all over again.

A lifetime of letters would fit in that dark wood box. But this letter would not be one of them. For this letter belonged to Lan Sizhui.

Wei Ying gazed at Lan Zhan and pressed a smile to his hands.

“Thank you, Lan Zhan,” he whispered, and turned back to the desk. He lifted the brush once again, and wrote against the silence of the snow.

Your father is wholehearted in everything he does. He is each perfect note of a song, plucked carefully and without hesitation. He worries fairly, and he cares profoundly, and even amid the thousands and thousands of Lan sect rules, he lives freely. And more freely than you might dare think! But I can prove it to you: in a little town outside YueYang, a yard tucks against the woods. If you sneak through the fence and search the gateposts, you might come across a pair of weathered carvings. And there you’ll see, plain as day, writings into the wood from both our hands:

Lan Wangji Was Here

Wei Wuxian Was Here, Too

Pages Navigation

wangxian+fan (Guest) on Chapter 1 Sat 23 Nov 2019 01:29PM UTC

Comment Actions

detention_notes on Chapter 1 Sat 23 Nov 2019 01:52PM UTC

Comment Actions

Live_Long_and_PawsPurr on Chapter 1 Sat 23 Nov 2019 02:00PM UTC

Comment Actions

detention_notes on Chapter 1 Sat 23 Nov 2019 01:59PM UTC

Comment Actions

scifigeek14 on Chapter 1 Sat 23 Nov 2019 03:13PM UTC

Comment Actions

detention_notes on Chapter 1 Sat 23 Nov 2019 07:22PM UTC

Comment Actions

luckymoonly on Chapter 1 Sat 23 Nov 2019 03:58PM UTC

Comment Actions

detention_notes on Chapter 1 Sat 23 Nov 2019 07:15PM UTC

Comment Actions

Lynne22 on Chapter 1 Sun 24 Nov 2019 07:00AM UTC

Comment Actions

detention_notes on Chapter 1 Mon 25 Nov 2019 07:26AM UTC

Comment Actions

in_seclusion on Chapter 1 Sun 24 Nov 2019 09:54AM UTC

Comment Actions

detention_notes on Chapter 1 Mon 25 Nov 2019 07:26AM UTC

Comment Actions

n-x-northwest (wendy_bird) on Chapter 1 Sun 24 Nov 2019 08:08PM UTC

Comment Actions

detention_notes on Chapter 1 Mon 25 Nov 2019 07:30AM UTC

Comment Actions

Kitsumi on Chapter 1 Mon 25 Nov 2019 01:21PM UTC

Comment Actions

Kitsumi on Chapter 1 Mon 25 Nov 2019 01:23PM UTC

Comment Actions

detention_notes on Chapter 1 Mon 25 Nov 2019 02:23PM UTC

Comment Actions

detention_notes on Chapter 1 Mon 25 Nov 2019 02:22PM UTC

Comment Actions

Marian3490 on Chapter 1 Wed 27 Nov 2019 05:37AM UTC

Comment Actions

detention_notes on Chapter 1 Wed 27 Nov 2019 04:02PM UTC

Comment Actions

annabane on Chapter 1 Thu 28 Nov 2019 04:35PM UTC

Comment Actions

detention_notes on Chapter 1 Thu 28 Nov 2019 09:45PM UTC

Comment Actions

neutrophil on Chapter 1 Tue 24 Dec 2019 06:00AM UTC

Comment Actions

detention_notes on Chapter 1 Sun 05 Jan 2020 05:02PM UTC

Comment Actions

Frans (Guest) on Chapter 1 Mon 27 Jan 2020 04:33AM UTC

Comment Actions

detention_notes on Chapter 1 Tue 04 Feb 2020 03:59AM UTC

Comment Actions

missdisaster on Chapter 1 Mon 02 Mar 2020 09:27PM UTC

Comment Actions

detention_notes on Chapter 1 Thu 19 Mar 2020 08:46PM UTC

Comment Actions

luvwangji on Chapter 1 Thu 05 Mar 2020 06:08PM UTC

Comment Actions

detention_notes on Chapter 1 Thu 05 Mar 2020 06:19PM UTC

Comment Actions

RavenXYZ (Guest) on Chapter 1 Tue 10 Mar 2020 06:50AM UTC

Comment Actions

detention_notes on Chapter 1 Thu 19 Mar 2020 08:44PM UTC

Comment Actions

enceleste (Guest) on Chapter 1 Thu 26 Mar 2020 10:37PM UTC

Comment Actions

detention_notes on Chapter 1 Sun 12 Apr 2020 05:22PM UTC

Comment Actions

makora (Guest) on Chapter 1 Tue 05 May 2020 12:35AM UTC

Comment Actions

detention_notes on Chapter 1 Fri 03 Jul 2020 05:24AM UTC

Comment Actions

jiuhuo on Chapter 1 Sun 17 May 2020 07:52AM UTC

Comment Actions

Wassermelonenpudding on Chapter 1 Mon 21 Sep 2020 01:36PM UTC

Comment Actions

wangxianshit on Chapter 1 Thu 29 Oct 2020 05:44AM UTC

Comment Actions

Pages Navigation