Work Text:

"Corpse man?"

He was glad that somebody else had said it out loud first, not him. The sergeant was annoyed and the lieutenant was snooty about it and a lot of the guys laughed, even the ones who had probably misread it the same way themselves.

He wasn't dumb. He could read and write as well as anybody. He read books just for fun sometimes too, especially if it was a good book, like the movies, with a car chase or a shootout, the cool aloof hero rescuing the sassy-talking girl. He could read well enough, and he knew that the word sounded like "core" like Army Corps or Marine Corps. But there on that paper, it sure looked like it said something else.

The lieutenant went on and on about what a great assignment they had pulled. They were going to serve in a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital and anybody that showed enough promise would train to be a corpsman.

Work hard and eat all your vegetables and you too can be a corpse, man.

That might not be what the papers in his hands said, but his hands shook just like they did. He'd heard about MASH units, right up so close to the front lines you could hear the shelling and that's where they brought back all the wounded, all mashed up.

The lieutenant said that being a corpsman meant treating the wounded yourself while the doctors were busy, but the sergeant said that it mainly meant carrying litters into the O.R. Someone asked if that meant a lot of blood and someone else said, "Keen!" and someone else made retching noises.

"And if we don't show promise?" someone else had asked. "If they don't think we'll be good corpsmen?"

The sergeant told them it meant the front lines, that if you were too stupid to be a corpsman then maybe you'd be better at catching bullets. The lieutenant reassured them that they were all good enough to train as corpsmen. They'd taken a test already, hadn't they?

He remembered the stupid test. Everybody called it the stupid test, because it was a test to see if you were stupid or not. He'd taken tests like it in school and never sweat it much. Who cared what a test said? If you did poorly they shook their heads at you and maybe suggested you consider learning a trade. If you did well, they gave you even more work to do. Punish a guy for doing well, go figure.

But they told 'em right up front that this test mattered. Because what Sarge said was right. No one was too stupid to be a meat shield, but not everyone was smart enough to manage an inventory roster back in Tokyo. Do well on the test, they might keep you somewhere safe.

He didn't know if he'd done well on the test or not. The lieutenant said a corpsman had to be smart so maybe he had, but if he were smart he oughta be able to think a way out of having to be a corpsman.

"Don't waste your time with him," one of the guys said. "He hasn't said two words to anybody." By the time he realized someone had asked him a question, the guy had moved on and gotten a light from somebody else.

"He's the mysterious silent type," someone else joked and that got a couple of laughs.

And what a laugh? Him? The silent type? Him? They'd bust a gut if they heard that back home. His own gut was twisted up into so many knots that he didn't have a laugh in him though. People walked by like shadows before he noticed they were there. It was like one of those dreams where you're walking through molasses and you can't control your body. You know the monster is there, but you can't run away. You see it and you're screaming at yourself to run away, but you're just stuck in the molasses. Monsters! Run!

He'd run already. Far and fast, just not very effectively. They nabbed him right off the bat and a guy built like a brick wall—a brick wall with a crew cut—had asked him if he wanted to serve his country or if he wanted to do hard labor for draft dodging. Call him a draft dodger, he wasn't proud. He wasn't proud at all. He was scared spitless was all he was, but he wasn't scared of hard work. Hard labor as a draft dodger sounded dandy to him and he'd said so. He'd said so loud and clear and the brick wall with the crew cut said fine and he said fine. And he'd gone quietly then, but someone pulled a fast one because he ended up in Korea all the same.

"Soldier!" The sergeant looked mad and the lieutenant looked embarrassed, which meant he'd missed another order. He heard them—most of the time—but he kept forgetting they were talking to him because no one said his name. It was like he didn't even have a name anymore. He was "Private" and "Soldier" and sometimes just "You there!"

He saluted the lieutenant because it seemed like the thing to do. The lieutenant saluted back and said to him gently, like he was a little school boy, "Dismissed, soldier."

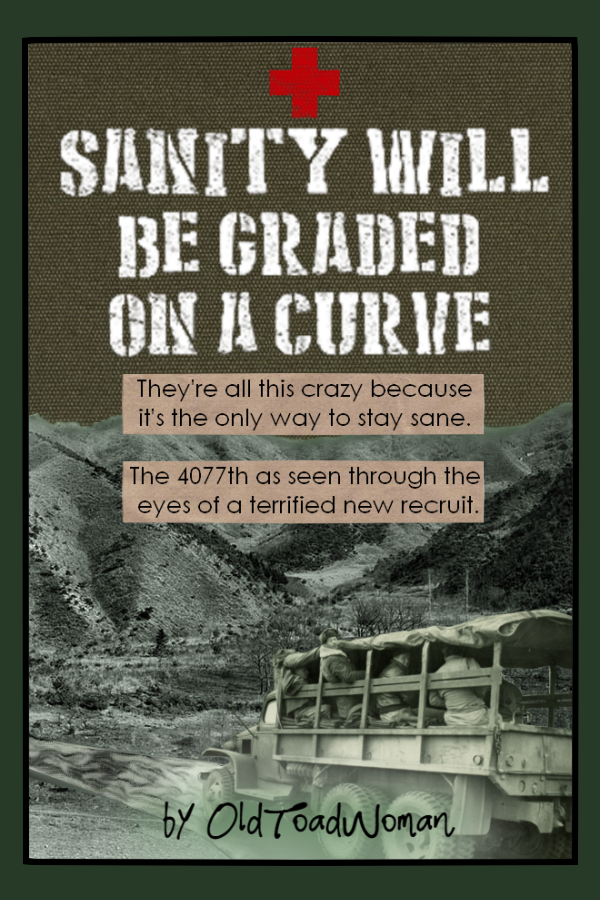

He realized all the other guys were gone, taken their bags and their rifles and their pieces of paper and left. He hoisted his duffel and his rifle, glanced once more at the piece of paper with "M*A*S*H 4077" on it, and walked out to the truck.

The entire world was gray. It was bright daylight and he could see crisp shadows on the ground. It should be a beautiful day; there should be color. It was just gray, sort of gray-green, army drab, maybe that was the color. But it was the color of everything, not just their clothes and the truck, but the ground and the trees and the hills. Nothing but a murky alien greenish-gray.

The truck moved and his stomach moved with it. His head spun and his heart pounded, but most of all his stomach lurched. One of the guys said the alien world looked like Italy and somebody else thought it looked like Napa Valley out in California and both guys agreed there ought to be vineyards just over that hill. He didn't know anything about Italy beyond sausage and gondolas and coliseums. He didn't see any of those things here and just thinking about sausage made his stomach flip over again.

They rode for hours or days or years or minutes. It was a jagged blur. The ride was rough and jolted his bones and his head hurt and this couldn't be real. Right now, this very minute, he could be sitting in the picture show with his best gal watching masked gunmen on horseback robbing a train or G-men taking out the mob or maybe his girl would have talked him into seeing some sappy love story with dancing girls in it. He liked the pictures with dancing girls too, but he was smart enough to never let on because sometimes she got jealous. Those girls had some legs though.

And now somehow he was inside one of the motion pictures. It was a war picture and he was a private and that was the bad part because war pictures didn't go so well for privates. Captains made it out of war pictures alive. Half the time they even got the girl. He couldn't think of any privates who had.

He had no idea how far they'd gone or where they were when the shells started raining from the sky. He watched the ground explode all around them, like water droplets hitting the dirt if you were the size of a bug, a tiny bug.

He didn't even think about his gun until the truck started to roll over. It tipped in slow motion, it seemed so anyway and maybe for real because he had time to grab his rifle and dive clear before it came to rest. He scraped his knuckles pretty bad and something cut a slice in his jaw back near his ear. It hurt like hell, but there was barely any blood on his fingers at all when he touched the wound. The sergeant and a couple of other guys sitting on the opposite side hadn't been so lucky.

The sergeant yelled, "Return fire, you useless bastards!" even as he lay pinned under the truck. The sergeant's pants were changing color and so was the ground. The guy next to him almost looked like something from a horror show, but only almost because Boris Karloff never oozed like that, not at all.

He hadn't even noticed the gunfire until then. Funny not noticing gunfire. Maybe it was the background music. You never missed the important parts of the picture, because the background music always let you know when the good bits were coming. The music reel was broken today. They should ask for free popcorn. It was only fair.

They returned fire.

(Every man who could stand, except the lieutenant, returned fire. The lieutenant ran for the far embankment and hunkered down out of sight. Good survival instincts these officers had.)

He returned fire too, but he wasn't aiming at anything except the trees. Trees didn't bleed. There was enough blood right here as it was.

They had to get the truck up. The sergeant was still muttering, "Useless bastards," so he wasn't dead yet, but the other two guys didn't look so hot.

He tried to get leverage on the truck while still hiding behind it, which wasn't working out so well, and a bullet pinged off the metal so close to his finger he could feel the breeze of the ricochet.

God damn it, wasn't anybody aiming at the enemy?

The lieutenant was still hiding behind the embankment. They could hear him screaming over there. You might say screaming like a girl, but if his girl had been here she'd have slapped him and told him to pull it together already.

All the sergeant could say was "Useless bastards" again and again, which was true enough, but his voice was growing fainter with each word. So, he couldn't say the lines either.

He knew the lines. Anybody who'd watched a decent war picture knew the lines. And somebody had to say the lines.

"Private!" he shouted. "You there! And you! And you! Lay down covering fire! Wide spread, aim low at the brush! The rest of you, help me move this truck! Now!"

And somehow it was over. They lifted the truck just enough to get the men out. The bushes stopped shooting back. He couldn't remember when the shelling stopped, but someone else said that was before the shooting even started. The next truck in the convoy caught up to them and loaded up the wounded. As an afterthought, someone got the lieutenant out of his hiding place, sobbing and pissing himself.

Those who could, and that included himself, walked the rest of the way to the 4077th.

He arrived exhausted and bloody, but hardly any of the blood was his own. He barely made it past the signpost when a couple folks came out to meet them. One was a weaselly fellow who reminded him a bit of the lieutenant. The man gave a speech about heroism and bravery and America and maybe apple pie too. He hadn't learned all the insignia yet, but the man had studs on his collar which said he owed the man a salute. The other was a woman and he didn't have to check her collar to know he owed her a salute.

The sergeant had been very clear on that. It was part of the fraternization speech. A woman in uniform was an officer. Every one of them. There were no female sergeants or corporals or privates in the United States Army. You see a woman in uniform, you say, "Ma'am, yes, ma'am" or you say "Ma'am, no, ma'am" and nothing else. You see a woman in uniform and you damn well better salute and nothing else.

One of the guys made a crack about how he'd been saluting all the women he met since he was eleven and that guy had gotten into a bit of trouble. Come to think of it, he thought that guy might be dead now. He really hadn't looked too good at all.

He snapped off a smart salute, for her sake, not the weasel's, and God bless America and Mom's Apple Pie that was worth it because without meaning to do it at all, he flicked a bit of blood onto the man's cheek in the process. Officer Weasel made a sound like a squeaky door hinge.

The woman sighed in a way that he was pretty sure the sergeant wouldn't have approved of. She was a tough cookie and more than just a little bit scary, all the more so as she smiled at him, him all covered in gore, and told him that he was a real man.

Ma'am, no, ma'am, I'm not a real man at all. I'm a walking, talking picture show. If I thought for a minute this was real, I might just have to take this rifle and blow my own head off. But it's just a motion picture, a war picture, but not a good one because our lieutenant has gone and pissed himself and I puked my guts out two miles back.

The majors—they called each other "Major" often enough that he got that sorted out soon enough—called up another private to show him and his men to their bunks. He sat on the edge of his cot and he waited, waited for someone to come and tell him what to do. He'd learned that much about the army already at least. There was always someone who'd come along and tell you what to do. More than anything, he was waiting for the usher to wake him up. He knew it wasn't going to happen. Deep down, he knew. But he waited for it anyway. There was nothing else to do.

He didn't know how long he sat there before he fell asleep or how long he'd been asleep. He woke up drooling on the rough army blanket, his toes aching inside his boots. The blood had dried on his shirt, but he'd sweated so much you could barely tell and he was cold despite the sweat.

"I didn't mean to disturb you," a soft voice said. "I could come back later?"

He blinked and sat up. "Naw," he muttered. "I'm awake." He wasn't sure that was true.

A chaplain, as pale as a ball of raw dough, was standing hesitantly in the entrance.

"I just wanted to welcome you," the chaplain said, tipping his hat. "My name is Father Mulcahy. I'm here if you'd like to talk?" It was both a statement and a question. "And we have regular services of course. All denominations welcome. Even here, we can find comfort in God's love." Father Mulcahy seemed embarrassed by his own words, as if even he knew that talking of God's love in the middle of a war was absurdity.

Love? What had he done so wrong that God hated him this much?

He'd heard the old saw. There are no atheists in fox holes. He didn't realize it meant this. Not praying to God to save him, but asking God why he'd been cursed with being here in the first place. He gambled from time to time if he felt lucky. He drank sometimes and his ma disapproved. He ate bacon without a second thought, even on Fridays.

"It's been quiet," Father Mulcahy said. "Your convoy was the only wounded we've seen in the last two weeks. It looks like you'll be lucky enough to settle in before we're busy again, which, God willing, will be quite some time."

God willing. There was a phrase he knew well. The old folks always said it. Not just when they were making big plans, like God willing, I'll be able to save up a nice nest egg for retirement, or Someday I'll have beautiful grandchildren, God willing. But even the little things. His grandmother wouldn't agree to tea without qualifying it.

Are you coming by for tea later?

I'll be there by three, God willing.

It was how you reminded yourself that God's will was all. That if God willed you should not have a nice nest egg by the time you retired or have ugly grandchildren or none at all or that you should not have tea at three or ever, then God was well within his rights to run you over with a bus if he wanted.

It was precisely this kind of logic that made him an atheist—most of the time, foxholes notwithstanding—because the conclusion to be made was that because he had scheduled a dentist appointment or promised to tie tin cans on some guy's car at his wedding and forgotten to say "God willing" that God the Benevolent Creator of the Universe had swooped down and said, Ah! Ah! Ah! You didn't say the magic words! And off to Korea you go!

He opened his mouth to speak and realized the father was gone. He hadn't noticed him leave. People came and went. Some of them may have talked to him. It was hard to say. Maybe they'd given him orders. He couldn't remember. He didn't worry about it. If it was important they'd yell at him. That's what the sergeant had always done.

The latrine was close to his bunkhouse and he'd staggered out that way a few times as nature demanded but he kept going back to his bunk. If he slept, there was always a chance he'd wake up back home. Click your ruby red heels together and open your eyes to Auntie Em. There's no place like home. There's no place like home. There's no place like home.

Had a day passed? Two? He was cold and he ached and his stomach hurt and he was starting to get dizzy. His body had a better sense of what he needed than he did. His nose located the mess tent and his feet followed it.

He was turned away near the entrance on account of being "more disgusting than the food" and was ordered to take a shower.

The guy who did the ordering looked like a private too, but he also had an apron on and his ma had taught him a long time ago that the person wearing the apron was the boss. You do not argue with the wearer of the apron.

He wandered the camp for maybe half an hour looking for the showers before he found them. It didn't even occur to him that he could have asked anybody for directions. The people he passed were just extras. They weren't paid to say lines. If they said lines, you had to pay them more. That's the way it worked.

The showers had water. No soap. No towels. You had to bring your own and he thought maybe he had both of those things in his duffel bag—which he'd rescued from the truck undamaged apart from the bloodstains—but his stuff was back in his bunk and he was here. He stepped into the cold water, uniform and all. He needed a laundry as much as a bath and he worried at the sweat and the bloodstains with his fingertips, doing little good. He undressed and squeezed the water and dirt and blood out of his clothing. He used his undershirt as a washcloth to scrub away the worst of the sweat and the grime. He rinsed the clothing until the water dripped mostly clear. And then because he'd brought nothing else to wear, he put the wet uniform back on.

He refilled his canteen and then walked damply back into the night, the cold night, wondering when it had gotten dark. He was sure it wasn't dark when he'd tried to go to the mess tent.

A cold breeze blew through him and he started to cry, really cry, not like a hero shedding a single manful tear over fallen comrades. He cried like a child who has lost his mama and scraped his knee and dropped his ice cream all while the monster from the closet creeps closer and closer. Run! Run!

This wasn't a picture show. Picture shows weren't cold and they weren't damp, not achy or tired or hungry either. He was in God-damned Korea and he didn't know why. It didn't make sense.

Maybe he was already dead. Did the dead feel cold and damp? He'd never imagined that they felt anything at all, but if they did, yeah, cold and damp sounded about right. He'd read stories like that in True Ghost Stories, ghosts who wouldn't shove off because they didn't know they were dead. Or because they couldn't rest until justice was done. This was going to be a long haunt if he had to walk the earth looking for justice. Where was justice in war? Could he go back and haunt the draft board? Could he haunt the brick wall with a crew cut who promised him a nice safe prison and delivered him back to the army instead?

His heart thudded painfully in his chest. He had to be alive if it hurt so much, didn't he? And everything inside him hurt, his head and stomach, especially his chest when he breathed. From the moment he got that draft notice, his world was one searing moment of blinding panic. He'd never realized before that panic hurt.

"Geez, you must be freezing," said a kid in a funny cap. "You're all wet," he added, just in case he hadn't noticed.

"I can't remember where I left my gun."

He hadn't meant to say that. He knew where his rifle was. He was pretty sure he'd left it on his bunk with the rest of his things. He just couldn't remember where his bunk was and now it was dark.

The kid said, "Oh," and nodded as if people misplaced firearms like car keys all the time around here. Maybe they did. "Do you remember where you last had it?" he asked.

"Bunk. There was a big..." Was it a building or a tent when the frame was made of wood but the walls were made of canvas? "They put us in this long thing..."

"Oh, hey, I know you. You're that guy who lifted a truck off his sergeant."

That wasn't how it happened. "There were a group of us. I think the other guys are back at the tent-building-thing."

"I just saw your sergeant in the med tent. He's doing real good. He's not going to lose his leg or anything. Isn't that great?" And the kid meant it. He blinked up at him with owlish eyes behind his round glasses and waited for him to agree that not losing your leg or anything was the keenest thing ever.

"Yeah. Great."

"Shame about the other two guys though."

"Yeah."

"I'm sorry. Were they friends of yours?"

"I didn't know them." He didn't know any of them. Were the guys on the truck the same guys he'd trained with before shipping out? He couldn't remember any of their names, the faces all blurred together.

The kid lead him back to his bunk and turned his back when he put on dry clothes even if none of the other guys did and then showed him what to do with his laundry.

"The important thing," the kid said, "is to make sure you've got a spare before you dump in your dirties. Because it's not always easy to find your size and people'll just take the good stuff even if you've sewn your name in it. And everybody's trying to ditch the ones with bloodstains, which come to think of it, you should have no trouble getting your stuff back okay."

He listened politely and tried his best not to faint from exhaustion, which he thought maybe would have been rude. He clutched his rifle like a rag doll, afraid of misplacing it again, but if the kid thought that was weird, he didn't show it.

After the tour of the laundry, he crawled back into his bunk and chewed on a ration pack. He probably shouldn't have wasted it in camp like this, but the mess tent was closed by then and his stomach was really starting to hurt.

The kid was there first thing in the morning again to show him his animal hutch. "I know you wanted to meet everybody," the kid said. He didn't remember wanting to see the animals, but it made the kid happy so he didn't argue. He didn't understand them though. Stacks of cages of little furry things, most of which you'd call pest control for back home, but the kid had rescued them from the war zone and the landmines and fed them things that might have been vegetables before the army got hold of them.

"What are they for?" he asked. "Do you eat them?"

It was the worst thing he could have said to the kid. The kid who was not fazed by bloodstains or the deaths of two privates or a crazy man who wandered the camp soaking wet in the middle of the night muttering about his rifle, this kid was horrified to the point of a spitting rage at the suggestion that he was raising his animals for food.

"We don't eat Daisy!"

"Sorry."

"We eat food! Or, y'know, that stuff they serve in the mess tent, but not Daisy or Mortimer or..."

He looked at something that looked like it might be a hamster or a gerbil or whatever they had in Korea and his stomach grumbled audibly.

The kid practically screamed and threw himself protectively against the cages as if he were going to just start gnawing on a bunny rabbit or something.

He left the kid behind and wandered off in search of the mess tent. He felt like he was starving to death. The food in the mess tent nearly cured him of that, but he ate it anyway.

The majors arrived while he was staring at something the man in the apron had called "grits" and he was trying to decide if he was hungry enough to eat it. It looked less risky than the thing that was allegedly "sausage" so he was willing to make an effort.

"This is our hero," the woman said. "He lifted a truck off his commander under direct enemy fire."

He looked up and realized he was surrounded, not just by the majors but by a number of others he hadn't met before, suddenly all sitting around and across from him.

A man with dark hair and improbably blue eyes clutched his hands together like a schoolgirl and breathed, "Can I have your autograph?"

"There was a whole platoon of us lifting that truck," he said coldly, "and the way I heard it only one of the three guys we pulled out from under it lived."

"Oh," the man's expression went serious in an instant, "that truck. Sorry, I didn't realize."

"Under enemy fire," the woman repeated. "Major Burns and I have recommended him for a promotion."

"Does Henry get a say?"

"Colonel Blake already signed off on it."

"Congratulations." A man with short curly hair reached out to shake his hand and when he just stared at him numbly, the man shook his fork instead. It was as if the war film had gone into intermission and they'd put a Bugs Bunny short on between reels. "Private first class, then?"

"Corporal," she said.

"Can you jump ranks like that? He doesn't even have his first class private stripes yet."

"Bravery in a time of war should not go unrewarded," she insisted. "With both of his superiors out of commission, he took command of his men, rallied them, cut down the enemy, and rescued his sergeant."

"We cut down shrubbery mainly," he muttered. If they'd hit anything else, he didn't want to know. What if he'd killed someone? What if they hadn't killed someone? What if they'd left someone in those bushes as bloody and mangled as the sergeant and the two privates had been, just left 'em there like that?

"Also," the weasel added, "we're now short a sergeant and a lieutenant so an extra corporal or two wouldn't exactly go amiss now, would it?"

"I heard the sergeant was going to be okay," he said, feeling the world slip away from him again.

"He'll be fine, yeah," the dark-haired one agreed, "pretty damn lucky actually. Limps just badly enough that he's got himself a ticket home, but once he gets fitted for a knee brace, he'll get around pretty well as a civilian."

"And the lieutenant? What's wrong with the lieutenant?"

The curly-haired one rolled his eyes and said, "Everything as far as I can tell."

"Cowardice," the weasel spat. "He's just faking to get out of doing his duty."

"Frank, he didn't eat for the first four days he was here," the dark-haired one said.

Four days? They couldn't possibly have been here more than four days.

"And he's got diaper rash," the curly-haired one added. "Do you know how crazy a healthy person has to be to curl up in bed on purpose long enough to get diaper rash? The kid's messed up." He tapped the side of his head for emphasis.

"Well, good riddance, I say," the weasel said. "We don't need his sort around here anyway. I hope he has fun in the loony bin."

"The lieutenant is going home?" he asked dully. The lieutenant hadn't been injured at all. Not even a little. How was this possible?

"Loony bin," the woman echoed as if to correct him.

"Stateside?" he asked again.

They all shrugged. "Tokyo first," the dark-haired one said. "If they can't sort him out there, yeah, maybe stateside."

How was that for a gas? Piss your pants and you get to go home.

"If it were up to me, we'd send all those cry babies straight to the front and give them something to cry about."

Or not. That was Sarge's attitude too. No one was too stupid to be a meat shield. Not a private anyway. A pissing lieutenant might find a ticket home, but a private, even a corporal, could not afford to be bad at the job at hand. There was always a worse job waiting.

A world of advice swam around in his head.

Good hygiene is the foundation of a good life, his schoolteacher said.

God Bless America and apple pie and baseball and hot dogs, the major said.

Do the job that's in front of you, his grandmother said.

Anything worth doing is worth doing right, Aunt Maxine said.

Prove your worth and you'll train to be a corpsman, the lieutenant said.

Screw up and you're cannon fodder, you useless bastards, the sergeant said.

Come home safe, Laverne said.

You write. From Fort Dix, you write many letters, his mother said.

Think. Always think, Uncle Abdul said.

You can never go wrong with pearls, Uncle Zack said.

"You can never go wrong with pearls," he whispered.

"I beg your pardon?" the lady major said.

"Sorry. Just thinking out loud." Max took a bite of grits and rolled his tongue around his mouth experimentally. They weren't bad exactly, but they were definitely well named. "Ma'am, do you know if any of your nurses have any mail order catalogs I could borrow? I'm going to need a few things."