Work Text:

We cross our bridges when we come to them, and burn them behind us, with nothing to show for our progress except a memory of the smell of smoke, and a presumption that once our eyes watered.

-Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead. Tom Stoppard.

Prologue.

Bletchley Park. 1941.

In the ninth century, the Kashmiri poet Rudrata buried in Kavyalankara, his commentary on Sanskrit poetics, an elegant literary contraption. It is a poem of eight lines; in each line there are again eight letters. When it was later found by Arab scholars in the eleventh century, they noticed with delight that the poem is a symbolic chessboard. You can read it in the usual way, left to right, line by line, or by moving on the poem according to the legal motions of the knight. Miraculously, the poem remains the same. The knight’s tour, they called it.

This story Remus often thinks of in his small Park desk—whether if he looked through his life he would also come upon such a palindromic symmetry; whether by a series of reflections the light’s bending path would reprise the same glittering narrative—or whether he would eventually come to the conclusion that his is but a single chaotic trajectory careening in the vast space of possibilities, an unstructured and careless curvature; that though beauty—the work, always the work—he had in ceaseless abundance, desire—its twin alchemical ingredient in love—he would have to rummage for in the ruins, among the cinders of Troy, in the wine-dark sea after the warriors have returned home empty-handed.

It is with particular difficulty that Remus conjures Cambridge, the Cambridge of his school days. The War had filtered its colours and muddled its geography. Some details he inevitably would get wrong: buildings were misplaced or omitted altogether; colleges were transposed to the wrong side of the river, or the opposite end of town. The names of streets and courtyards often played a game of musical chairs, landing haphazardly upon random places, so that space and nomenclature were estranged in his memory, and he kept track no longer the sequence of events with the photographic precision of his professional wont, but filled its gaps and edges with a fictive urge.

In his days Cambridge was a place of stasis and unchange. To Remus it seemed a strange city, completely at odds with the first London of his boyhood and the later London of his adult life—a city where hunger and thirst were the unknown needs of an unknown class, and desire a taxidermied beast shorn of fur and fang. And yet, paradoxically, the same becalmed and parochial Cambridge had set in motion his eternal unrest, had summoned in its courts and streets the life-long cast of characters he would live with and love with—had taught him not only the axioms and theorems of Hilbert but also the boundless private empire.

I.

University of Cambridge

1932. Lent term.

Morning stole upon him in a rare rain of light. Remus John Lupin, like some rare shy creature, came out of his rooms to sound of the Chapel bells ringing for Sunday service.

He lit a cigarette. It eased his head; he was having an ill morning, hung over from the champagne and Cointreau of the night before. Down by a willow tree in the Backs he found a peaceable parcel of footpath and sat down. The river swelled high in its banks—moorhens floated on the limpid green water, preening their wings. The watery, rained-upon scent of late March pervaded all. From his vantage point the Chapel was in full view: it was darkly splendid, its barbed finials a ctenoid progression along the high Gothic entablature—beautiful, though most beautiful in winter, with the snow revealing all its angles. An organ’s slow crescendo rose from within—its cornopean voice mixing with the choral tenors, ringing out the boyish notes of Anglican piety.

Sunlight shifted among the bare willow branches.

This is Cambridge he most likes to remember, in the green grip of spring, where hidden among the spreading elms and chestnuts, Remus could often feel an echo. As if the men of centuries past had slipped by him on the ancient flagstones of Trinity Lane, and walking down King’s Bridge he brushed shoulders with history still living; the Cambridge where time itself was a crumbling fabric, here thin and here folded, and now and again he could hold it and examine not only his own meagre portion but its extraordinary breadth; and on the street corners he found the casual shadow of Milton or Maxwell or Newton, those fluctuating ghosts upon whom he peered, like a child in a long gallery of venerated portraits, though it was not their likenesses, but their minds that he saw.

The cloistered mood buoyed him from his headache—like a conductor he summoned to mind his current readings. Structures emerged with them, brushed from the misty chaos of nature: meticulous visions of Riemann’s geometries, of manifolds and tangents, of unfolding functions bearing the adjectives of art—complex, transcendental, harmonic.

“What have we here, a dreaming scholar?” A voice called behind him.

It was James Potter, smirking down at him form the gravel path.

“Good day, James.”

“You brazen infidel. Are you missing your Sunday service?”

“I don’t see what business it is of yours.”

“Do you realise that the development of a sound moral character is tantamount to your King’s education? One day they’ll drag you before the dean to explain yourself.”

Remus rolled his eyes. Slughorn, their dean—a funny little man with an anaemic understanding of maths and the sciences who fancied himself privy to the private moods of his “young men,” much to Remus’s distaste—proved quite lax in his enforcement of mandatory spirituality.

“James,” Remus replied rather wryly. “You know quite well that I’m a—“

“—atheist.” James supplied.

“—Jew.” Remus finished. He gave him a look. “Besides, I could levy the same charge against you.”

James grinned mischievously, “Speak plainer, Lupin—are you accusing me of atheism or Judaism? I can hardly pick which one is more delightful.”

Cigarette smoke rose up between them in slack tendrils. “This bantering will get us nowhere. I know what you’re doing and it won’t work.”

“Come now Remus, don’t be so prickly.”

They fell into an amicable silence. Remus had always felt a strange affection for James, though he often wondered why the affection was reciprocal. They met at college Remus’s first year; James was a year above him and roomed across the hall. He was an Old Etonian—his father a Liberal MP. He read Political History and spoke at Union, and was generally well-regarded by all the sectors of college that mattered. His singular record of blemish seemed to be his unconventional friendships, its chief figure of controversy being one Lord Sirius Black, Viscount of Alington, heir to the Earl of Hayneswick. It was said that even at Eton they had cultivated a reputation for insolence and brilliance. By Lent term of their first year James and Sirius had conceived of a secret society—the Marauders, they called themselves. (Remus had been inducted a term after, as was Peter Pettigrew, a mild Rugbeian and childhood friend of James’s, whose lack of exacting charm was more than doubly recompensed by his possession of a motorcar). They were known for regularly being found in the town pubs (which were off-limits to students), sneaking off to London, and giving cocktail parties, often ending in drunken scavenger hunts that became more and more absurd and ambitious.

Presently, Remus offered James a cigarette. “Have you talked with Sirius? Is he cross with me?”

“Oh Remus. Don’t be so stiff. Just apologise for being an unseasoned drunk.”

“I’m not very fond of drink.” Remus replied placidly.

“Well, then you must promise—at least to me—that you’ll right your ways in the future.”

Remus sighed. “I have very little hope of that.”

“You know, you are most serious, Lupin. Sometimes I fear we shall lose you altogether.”

“How do you mean, lose me—to what, death by melancholy?”

James laughed. “I dare say, Remus. Must it always be like a sordid Restoration play in that head of yours? I’m afraid for you it’s to be a much more romantic death. My prescription is dipsomania—a cure for your alcohol allergy. Or maybe you’d turn to the cloth—you know—for maths, your darling religion. I still can’t believe you’re reading a maths Tripos at King’s. I can’t think of a worse place for it, or a worse subject for King’s.”

“Well, it’s the only place that would have given me any money,” Remus remarked. “And one doesn’t die of dipsomania, much less I.”

“Oh, of course not.”

“And mathematics is not a religion.”

“Of course it isn’t.”

“And I happen to like King’s.”

“Of course you do.” James grinned. “It’s all on account of me, you know.”

They lit more cigarettes—the last two of a pack of Dunhills that James had on his person—and wandered toward the college gates.

“Well, well, Mr Lupin. What would you like since you seem to be so particular this morning.”

“For one, I am absolutely famished.”

“Shall we have luncheon? But not at college, dear God no. Let’s to the Copper Kettle. Oh don’t look at me like that—I’ll pay for you and you are not allowed to complain.”

—

The day after he found Sirius and James at the Backs near the Trinity grounds.

“Remus!” they called. Remus went and sat down by them. They were lying prone on the grass and it seemed they had been drinking. Sirius resumed his conversation with James. “As I was saying, everybody in London was still talking about the princes’ return.”

“Well, the Prince of Wales does seem to revel in the attention.”

“But it’s such a bore—“ Sirius turned to Remus to explain. “My cousin gave a dance in London last night. They forced me to go. Entirely dreadful. Half the old codgers in London were invited and the other seemed to show up anyway. She’s to be married to some awful American.”

“He’s quite up and coming, from what I hear.” James remarked.

“I’m sure—who should have know there was such a fortune selling light-bulbs half around the world?”

“Well, whatever fortunes they may find, I find them a rather awful lot to deal with.”

“Oh don’t misunderstand me. I find them fascinating. I just can’t decide if they are unaccountably boring or the most exciting race in the world.”

James gave him a look.

“Don’t you see, James, they have at their advantage a certain savage charm—all that trading and swindling and bribing. Positively alive.”

“Well, I find them as unpleasant as they come.”

“Of course you do, Jamesie. You know it’s your damned English breeding—you can’t seem to help but find unpleasantness in everything.”

James gave a long suffering sigh. “To be called well-bred by you, my man, might be the single most slanderous thing anyone has ever said to me.”

“The pleasure is mine, I’m sure.”

James rolled his eyes. Then checking his wrist watch he announced that he was due to meet with his tutor in an hour and he hadn’t done any work at all. He bid them goodbye—and Remus was alone with Sirius.

Lord Sirius Black was eccentric the way that only Old Etonians were allowed to be; he neither challenged nor upheld the conventions, instead toyed with its forms and boundaries like a bored predator eyeing too small a fare. He read classics and complained of the shallowness of the fellows, often volubly and often to the fellows themselves. He had a gift for music but favoured the curious works of the Russo-French avant-garde and not, as was thought proper, the old Germans. He was gregarious and gave many parties in the aegis of the Marauders Club, the invitations to which held ample promise of tipsy by noon and drunk by three, and did nothing to assuage his reputation of dissolution.

They had first met at such a party during their first year; everyone was to come to Hotel Felix costumed in celebration of the vernal equinox. They had dined and drunk in a boisterous racket—one came dressed as a cherub, another in the robes of a great sultan (complete with impractical headwear); Peter made a passable pirate while James, in a flash of inspiration (though not physiognomy), came as Byron in Grecian garbs. Some grouped in comic juxtapositions of figures—a Bolshevik talked amiably with an Elizabethan courtier and Caesars jockeyed with pharaohs. A gaily garbed Piers Graveston at one point shouted from the tabletops the ditties of Edward Lear. Remus (himself a sobering Orpheus, borrowed from the college acting troupe) had been hiding in the gazebo in the courtyard, nauseated with drink, when Sirius appeared—at the vortical centre of it all, dressed as Comus, the god of excess. He was stumbling. A dark Florentine Gabriel he looked, stepping out of the satin robes of Botticelli into a loose pale cloak which shone in the shard of moonlight. A wreath of wildflowers hung askew on his brow. His eyes, so often dark and sullen, looked upon Remus with an air of open amusement. “Hullo,” Sirius said, slurring, “you must be Remus—the fey little scholar James keeps telling me about.” Sirius was not a little drunk. He extended his hand in greeting and promptly fell onto Remus’s shoulders. “Oh dear—” Sirius giggled. “What a wonderful name you have—where is your twin, I wonder.”

But presently Sirius was bored. He tossed aside his grey flannel jacket and sprawled out on the grass. “How was your day?” he asked in a flat tone.

“Nothing too exciting, I suppose. I just met my tutor—he seemed quite happy with my progress and gave me leave to cut lectures next term to work on my exams.”

“Gave you leave! The nerve of the man. I suppose next he’ll give you leave to sneak off to London soon—it seems quite presumptuous of him.” Sirius smiled rather wickedly. “My tutor at least gives me the courtesy of pretending that I’ve been to lectures all term and answer all his calls.

“But my God, Remus. Your Tripos sounds like a ghastly business—where you’ve come by your work ethic is a permanent mystery to me.”

“I’ll take that as a compliment.”

“Well, that is where you always err. I should think that I never give compliments, especially to my friends.”

“Is it because they are unworthy of your compliments—or your compliments unworthy of them?”

Sirius laughed. “Oh Remus. Don’t be facetious—it simply suits you too well. You might have to give up on being earnest—a quality of utmost importance, or so I hear.”

“Did you now?” Remus wondered, briefly, at that turn of phrase. The works of Wilde had been so thoroughly banned at Sherborne that Remus knew nothing but a few titles; but at Cambridge (at least among friends of Sirius) they were common fare, and Sirius was often seen with a copy of The Picture of Dorian Gray in his blazer pockets.

Sirius grinned and said fished his cigarette holder from his jacket, “Well, I won’t attempt to offend you further. I was rather hoping you’d sneak off to a pub with me tonight—with or without your tutor’s leave.”

Remus sighed and took a cigarette from Sirius’s holder. Sirius smiled.

—

Easter vacation came and went. Remus began his first Tripos preparations, but when his morning’s difficult readings had muddled his thoughts, and he could no longer sit still in the library, Remus would end up in Sirius’s rooms. He could not quite say what drew him there, but if pressed, Remus might have said that he found Sirius an exquisite company, or that he was absolutely fascinating. Sirius was, of course, all these things.

Sirius’s rooms were the highest rooms in New Court, and whimsically furnished; silk imitation flowers littered its tables and red drapes replaced the austere college hangings. Sirius would fiddle on the upright piano with which he set to melody his fragmentary translations of Stesichorus, and Remus would read in the wicker chair by the window.

“Oh, what use are these!” Sirius would decry, flipping through Remus’s readings and work. “What a lot of strange notes. Your Greek is atrocious!” (He pointed to the jumbled equations of tensors and Remus laughed at the joke.) “Also your English seems to be littered with German.”

“Well, the original paper was in German, so it seemed natural to take notes in it.”

“Do you speak German?”

“Not quite. I learned it all through mathematics texts.”

“I suppose you know all the words of logic and algebra but not a single word to ask for directions.”

“Something like that.”

In the early evening they often went down to the gardens, and Sirius would recount with surprising alacrity the nomenclature of the crepuscular butterflies that filled the flowers, or else Sirius met up with the others and snuck off on their illicit pub hops (which more often than not ended impassioned speeches and silly pranks) and Remus went sulkily back to his own rooms to work on his proofs without distraction.

—

On the last weekend of April, Sirius showed up in Remus’s rooms in a positive cloud of excitement.

“Remus!” He came bounding through the door, dressed in a white linen jacket and low Wellington boots.

“Oh, Sirius. I’m afraid I wasn’t expecting you.”

“I hope you have no plans today, my dear,” Sirius declared. “I’m going butterfly hunting, and you must come away with me. Look—I’ve brought two nets.”

Sirius took an apple from Remus’s sitting room table and walked over to the windows, talking excitedly. “I have a feeling that we’ll be quite lucky today—the temperature is perfect and there is no wind at all. We’ll have to skip tea, but we can bring some food—oh please say yes.”

“All right, all right. Let me get dressed.”

“Excellent! I’ll be out by the garage. Let’s get far, far away! The racket of the undergraduates scares away all the good insects.”

They borrowed Pettigrew’s motorcar and drove west toward Grafham Water, along which dotted the kind of East Anglian copse that proved ideal for a good haul. They trekked out, Sirius scouting with his binoculars and Remus following behind.

It was the kind of late April day that held on the high cusp of summer, as if aware of the invading heat, so that each colour became more alive and each form sharper. Sirius was looking for a particular butterfly that day—the elusive Black Hairstreak, a rare English sight. Days before he thought he had glimpsed in the botanical gardens its flash of orange and umber, and upon a tip from John Curtis’s British Entomology he sought its shadow in vain among the anemones and harebells of Brampton Wood, where catch after catch they found only its concolourate mimic, the Brown Argus.

Deep into the forest they trod, creeping beneath the thick canopies, hiding here and there behind the knobby grey boles of ash, while their Fritillary prey roosted and glutted on the azured harebells spread below them like the sweetened grave of Fidele. With catlike motions Sirius stalked, in the rhythm of the wind, stopping and moving and stopping again, steadying his limbs, twisting his net, and whoosh!—it would swoop up and within its gossamer webs would be caught a butterfly.

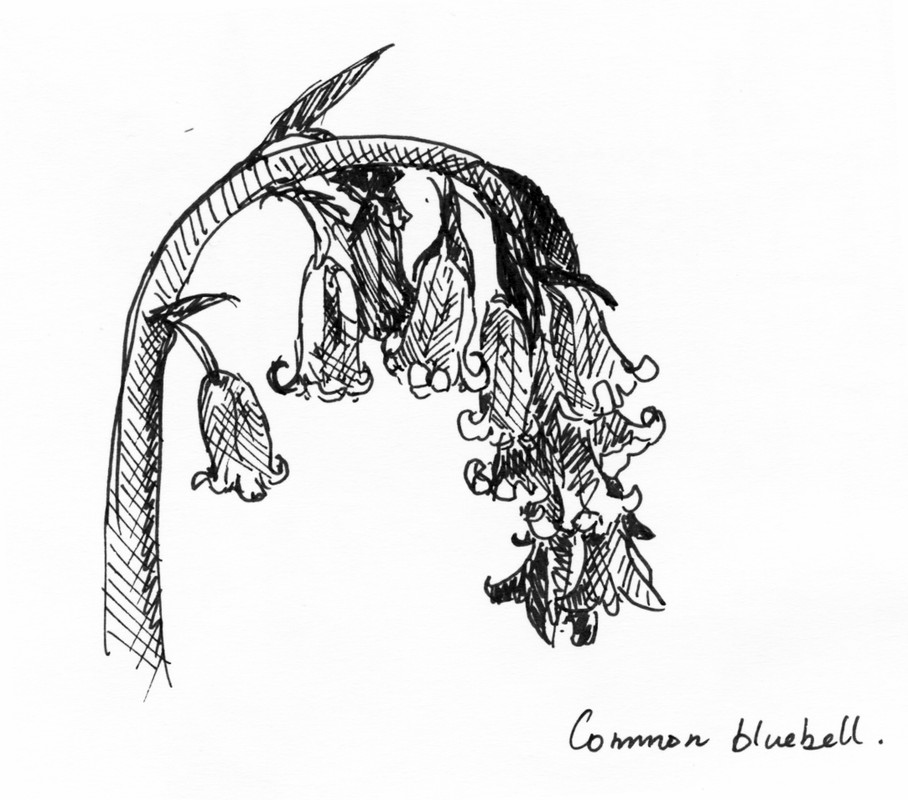

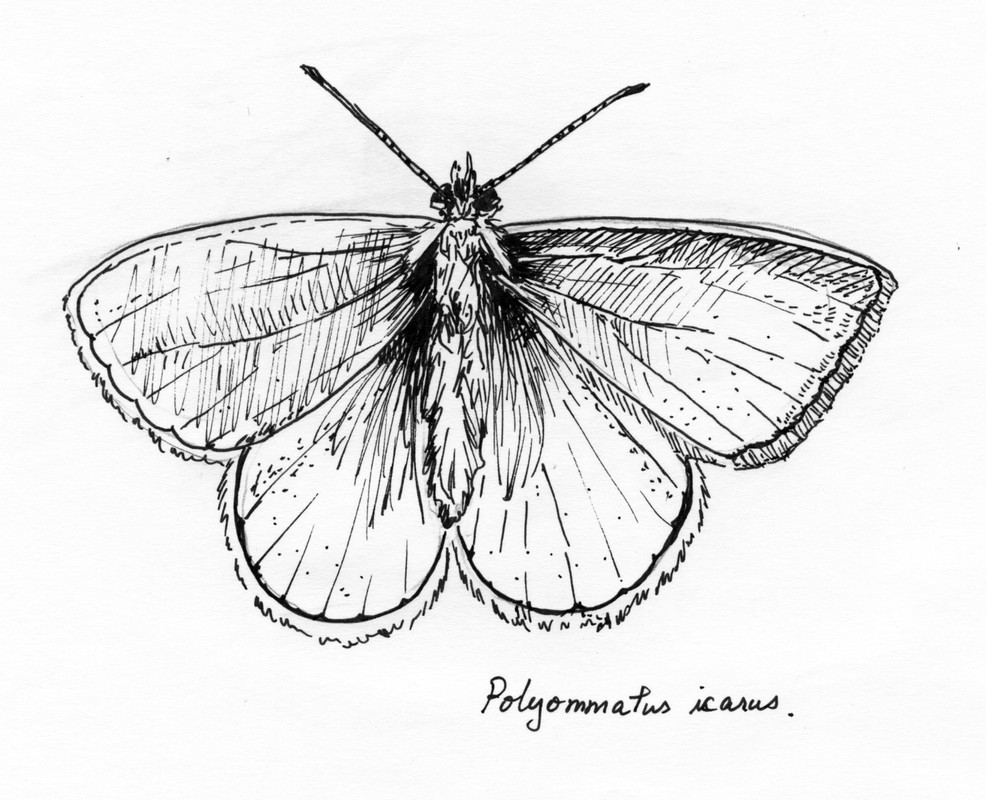

Sirius pinched its thorax and deftly folded it back. “That’s a shame. It’s only a Common Blue.”

“I guess that means it’s not rare.”

“No it isn’t. But it is quite beautiful.” He held it by its body and lifted it to the light.

In the cottony sunlight which suffused the wood, Remus remembered the wings’ slowing beat, the throbbing and folding which marked out the sweet afternoon air. It was entirely cobalt blue, with a shimmering rim of pale white frills and veins of silver dust shot through its wings.

“Its Latin name, ironically, is icarus,” Sirius said. “Here, get me an envelope. There’s some in my bag.” He took the folded butterfly and carefully laid it in a layer of blotting paper, then the envelope that Remus handed him.

“Remus, do you know about metamorphosis?”

“Enlighten me.”

“When Lepidoptera grow large enough as caterpillars, they crawl up under some stem or leaf and wrap themselves in a chrysalis. That much you probably knew. But if you were to cut open the shell, you’d find nothing—absolutely nothing—of the original caterpillar—the head, the body, all gone! All that remains is this soup, out of which emerges the adult butterfly.”

“How strange.”

“It’s as if an entire world was dissolved utterly into chaos, and yet out of that mess a beautiful new world emerges. It’s absolutely Hegelian.”

Remus considered this. “I wonder how information from the larva is transmitted to the butterfly—whether wrapped deep in the soup there is some…crystalline centre where the larva was hiding all along. This reminds me of the theory of linear algebra. If you can define the image of a space—which is its shell—and its kernel—which is the heart, then you have uniquely identified it.”

Sirius scoffed. “It’s astounding to me how you seem to find mathematics in everything. Here, you can keep this one—I have too many of these.”

Remus held the envelop to the light—through its diaphanous texture he saw the outlines of the butterfly’s wings, its two unequal curves folded symmetrically; he said, “How will we preserve it?”

“I’ll have to pin it when we get back. I’ll do this one just for you.”

They ambled and hunted until at last they grew hungry, and made a picnic of the food they brought in a clearing. They read in the afternoon light, and dozed off one after the other. When they woke it was quite late, and they packed their things and walked back to the car.

“Remus, what do you think of God?” Sirius asked, out of nowhere.

“What?”

“I understand that your family is—“ he paused, “—Jewish, but what do you think?”

Remus was caught off guard. “I confess that I do not.”

“Do you believe in sin?”

“I believe in human morality, if that’s what you mean. But without a God there seems little ground to discuss sin.”

“I rather think I used to believe, but somewhere I seemed to have misplaced it.” Sirius paused. “You know, the Greeks did not believe in sin. They believed in human nature, which they shared with their gods. They believed in right and wrong but not sin—not like the way we do.”

Remus thought he heard a hint of rawness in Sirius’s voice. He had never seen him so earnest before.

“I had a little talk with my mother over Easter,” Sirius continued. “Apparently she had been hearing horrid things about me. She thinks that I’ve become some sort of degenerate—if only. She did insist that I go to Chapel though. She was inconsolable. Oh, I can’t understand her.

“All they keep telling me is how I must upkeep the family reputation. What a reputation! All my relatives are either pompous country bores or awful zealots. Does your family—do they give you trouble?”

“No. Not at all. My mother should have, but she died when I was young. My father is completely irreligious.”

“I envy you then—at least father wasn’t home. He would have been quite bloody about it, I’m sure.”

“I would not say that if you knew what it was like for me. In first form they used to glue my desk lid down so I couldn’t open it. I suppose it’s standard to prank the Semite. It got worse before it got better, though by sixth form we were mostly at an impasse.”

“Good God, what a bunch of brutes.”

The woods rustled in a sudden gust; the day dwindled. Remus blushed and looked away.

“What a strange thing—parents. Here are two people in whose likeness you are, yet from whom you are utterly alienated. Do you like your father?”

“I like him enough. He’s a financier. He’s rather tedious but harmless. They say that he has not been the same since my mother passed away, but I do not know.”

“Sometimes I wonder why we are the way we are.”

They drove back in the dusk.

Remus was silent. Their talk had precipitated a violence in his mind and he wondered what Sirius had meant. The road shimmered in the dusk, and he had the strange feeling that something had changed.

He was reading the papers of Einstein at the time, and its frame of the structure of time and space inevitably crept into the long ribbon of road, into the low fading light of the afternoon. Their shadows stretched into thin, wiry creatures beneath them, two untouching ghosts—and it seemed like they were chasing them, towards the wooded eastern horizon where Remus could no longer find the same Cambridge that he left, for in the intervening afternoon time had moved along its negated coordinate, and space changed with it—there was no retrieving time, no way of reversing its effects.

He lit a cigarette and peered at Sirius beside him—in the shadowy tenderness of their surroundings he was especially beautiful, especially affecting—and Remus thought he felt, along the speeding side glance and the retreating road, love like a faint bite, sinking into his heart in a singular, fantastic wound.

—

The next week, Sirius gave a small luncheon party. It was an informal affair, with only a few of their friends and acquaintances in attendance. Potter and Pettigrew, of course; Henry Huxley, cousin to the famous Aldous; George Nesbit, an Anglo-American who was head of the Fabian Society; two “White Russians” from Trinity, Mr Tohl and Mr Lanskoy (counts in nothing but name), whom Remus did not come to know well, for they sat apart and lapsed between themselves into the slow sonorities of their exiled language. They proved an eclectic bunch, their meal dissolving into a maelstrom of criss-crossing conversations, with Nesbit and the Russian gentlemen engaging in a particularly heated debate on the Soviets, though in the end the peace was kept.

After everyone had gone and he prepared to leave, Sirius begged Remus not to go.

“Oh Remus, don’t be a bore. Stay a while. Here,” Sirius said and opened a box of cigars. “We’ll have some cigars and go punting.”

So Remus stayed. They pierced and lit the cigars, sat on Sirius’s wicker-chairs and began a game of chess which they soon abandoned. (When they came back to it a month later, Sirius failed to resume his advantage, resulting in checkmate in eleven more moves by Remus after pinning Sirius’s overextended queen and decimating his ranks.) They talked about Remus’s studies, a topic of endless fascination and controversy, of the Bloomsburies, of the Bertrand Russell Affair, and inevitably of the War.

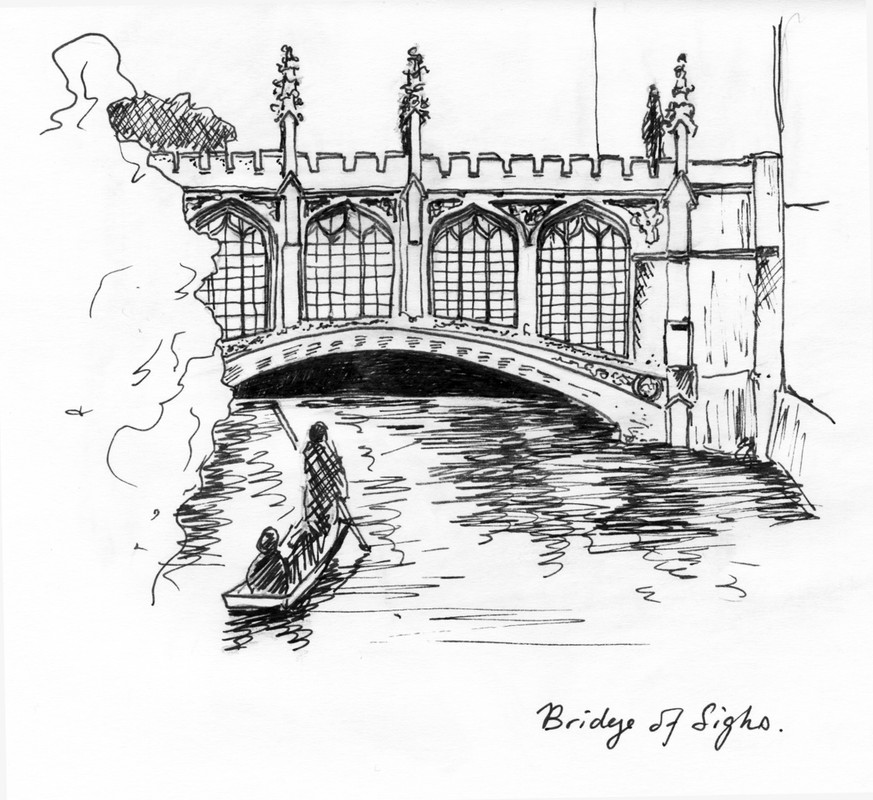

When their cigars were burnt to a stub, they went down to the river and took a boat. Remus stood steering while Sirius lay supine. Beneath them the Cam was a blue mirror, a hapless double sky. They floated on, almost frictionlessly it seemed, through the light filled air. Chestnut petals spiralled into the water to meet their reflections. Remus watched Sirius’s face in the dappled light, blooming dark and bright by turn. The sun played on his shirt, silken and dove-white, which caught his dark hair in relief. The form of him seemed to be a tessellating part of that afternoon, fitting into its frame as pleasingly as a jig-saw piece.

When they neared the Venetian bridge at St John’s, Remus banked the boat. They sat watching other punts drift by, and listened to the sounds of spring carried by the water—the bells of St Mary’s chiming for four, the chatter of ducks, and men’s laughter, filtered by the distance.

“Remus.”

“Yes?”

“Are you happy?”

“At this moment, yes.”

“But what about out of this moment—will you be out there, with their lot—“ Sirius gestured vaguely. The sleepy sweep of his fingers, Remus thought, in the moment containing only the courtyard, the church steeples, seemed to expand until its shadow hung over all of England.

“I can’t say.”

“What are you doing after we go down? Are you staying for an MA?”

“Yes—if they’ll have me.”

“And you’ll be a fellow after, I suppose.”

“Yes—do you think me terribly dull?”

“Oh Remus. Of course I do,” Sirius said quietly, almost wistfully. When Remus regarded him he seemed faraway and at ease.

From below the river came more bells, more laughter, more birds. The city flowed past them. They lazed together for a long time—while parasoled boats drifted upon their riverside doubles and the passing glances of their oarsmen seemed unable to pierce their intimacy; and time itself, Remus thought, seemed to cease its inevitable onward course, as if the falling flowers could have just as easily left their reflections and drifted backwards, upwards, growing back into the supple young branches, their cells fusing one by one into a single, magical beginning.

Remus took Sirius’s hands into his own and kissed them, multiply, on their fingertips. “Oh, Sirius,” he whispered, but Sirius had fallen fast asleep.

—

Remus could not sleep that night. He wandered listlessly in and out of college, and without thinking came into the Trinity grounds, into New Court with its medallion-like lawn, under the high windows where Sirius Black’s rooms overlooked the central chestnut tree—beneath which supposedly Newton himself sat, centuries ago.

A few out of dress Trinity men wandered about, regarding him with disinterest. The violets blooming by the flowerbeds made the air precociously sweet. The windows, with their vine-wreathed recesses and double-lancets, were dark. Sirius was not in.

Remus stood in the court. He felt the cool night on his skin.

What he wanted was like a garden whose founts and rivers ran with unseen powers—a secret garden that flowered in the centre of the city, but to which he had no map and no key, and its unscalable walls are risen up before him, and he could not even glimpse of its copses through the thicket.

A mist descended upon him.

He waited until at last the college gates were shut and he had to summon the porter, yet the windows never showed any light.

He groped his way back in the opalescent mist, stumbling on the street stones. He felt withdrawn and shaky. Unreal city, under the brown fog of a winter dawn—the phrase danced in his mind, a fragment of Eliot he’d gleaned from a book of modern poetry in Sirius’s room. The amber globes of the street lamps were barely visible above him, flickering in the still, diaphanous night.

—

The impending exams made the rest of his Easter term busy, and Remus did not seek out Sirius again. Once or twice on Sirius’s call they went out butterfly-hunting, but came up with only disappointing bags of brimstones and skippers, which they released.

His exams went as well as he could have managed; some of the fellows had been impressed with his papers on probability. He’d gone down with a first, much to Sirius’s amusement, who true to nature proceeded to both congratulate and reprove him.

During May Week, they eschewed the bumps and skipped to London in Pettigrew’s motorcar. Peter was for the Troc, but at Sirius’s insistence they went instead to the Chimera Club, a hidden spot in the upstairs of a lacklustre little townhouse in Soho, a suggestion met with almost unanimous scepticism. However, Potter remarked once they were in, “I say, Sirius. This is much, much more promising than I thought it would be.”

Remus, on the other hand, felt rather unsettled by its glamor. The main ballroom was dimly lit and not particularly large, but the countless small mirrors that overlaid its walls lent it an illusion of being spacious. The walls was high and prettily covered, with bright, Fauvist paintings on display between the Moroccan hangings. It was boisterous and crowded and the woozy sounds of jazz wove among them like thick smoke.

When they were seated Sirius went on to explain, “I had met the most extraordinary actress last summer here. An American—Miss Banks—from The Dancers. We were utterly drunk by the end of the night. Most entertaining girl. She told me her first show had been judged by the Wright brothers. I told her that she was an absolute femme fatale. We went for a drive in her motorcar, which she was atrocious with; we ended up at the river because she missed all the turns. Oh James, you should have been there.”

Peter perked up, “So those rumours were true! About you and some American entertainer.”

“I’m afraid it’s not up to what they all hope it is.”

James smirked, “Well, if you are being coy about it then is a shame I wasn’t there.”

“Come now, my dear Jamesie, we all know that jealousy is the heart of discord. Besides, there was nothing to it.”

“They also say that the secrets one keeps from his friends are the only secrets worth knowing.”

With something not unlike regret Remus pictured the American, some elegant and worldly creature, roaming in the dark deserted London streets with Sirius at the dash, going God knows where and doing God knows what. Remus let Sirius order his cocktail (Pimm’s and curaçao) and tried his best not to feel uncomfortable. They lit cigarettes and talked about the music, which they thought too loud, their acquaintances, whom they did not much care for, and the upcoming season, which all agreed was going to be a bore. Pettigrew got up to dance with some young lady, and subsequently disappeared to the upstairs bar. A certain Lady Daphne, youngest daughter to Earl of Stafford, spotted them and sat down with Sirius. James, at this point rather drunk, amused himself by keeping commentary on their conversation to Remus.

“Daphne, you are being most egregious—”

(“Oh do go on, my ego is only half inflated—”)

“Oh Sirius, but you do look so lovely—”

(Why don’t you compliment me—”)

“I shall be ever so disappointed if you won’t dance with me—“

(“I am quite uninterested in dancing—“)

“Well, I think I shall dance only if you’ve been nice to me—”

(“Please, do ask me to dance—”)

Sirius, wise to what was going on behind him, turned to glared at them; they traded grins amongst themselves.

By midnight Remus had lost a cufflink. He spent a good portion of the night dancing with Lady Daphne’s friends and bantering with James about it. At some point they both had to restrain Sirius from shouting through the club windows, trying to recite what he remembered of Lewis Carroll’s “The Hunting of the Snark.” When the club closed at two, Sirius telephoned ahead and they went to his family’s town house. They had eggs and more whiskey brought up, and sang raucous songs amongst themselves in the sitting room until they grew at last sleepy and went up one by one.

—

“Remus.”

“Remus.”

Remus felt strange. It seemed he had fallen asleep in his evening dress, which was stiff and uncomfortable. He also did not seem to be in his college rooms, a fact he noted dully as he reluctantly opened his eyes.

Sirius was sitting next to him, still in his pyjamas.

“Finally, you’re awake. I’ve been so bored being alone in the house.” Sirius said sulkily. He lay down next to him. “I feel awful. My head feels ten times its size and my legs have run off somewhere.”

“I—” Remus’s voice cracked. “I need to change out of this shirt.”

“I’ll have Lane bring you something of mine.”

“Where’s James and Peter?”

“They’ve both gone. It’s just us left.”

“Oh.”

“I suppose we should get back, too, before they notice. Not that they’ll like make a scene this late in the game.”

As soon as Remus was dressed they took breakfast and caught the eleven o’clock train down. Sirius took third-class with him. They nursed their hangovers and leaned against each other as they dozed. When they arrived in Cambridge their spirits were not much better.

Sirius, in particular, was in a morose mood. “I wish I could run far away,” he said suddenly, watching the train leave the station.

“Where would you go?”

“Just—away. I would ride on a train forever.”

“Forever is a long time.”

“Not if I go to the end of the world—just me against them all.”

“Sirius, what’s the matter?”

There was a long pause.

“Oh Remus, I wish you could understand.” Sirius said finally, in a sobering tone. “It’s only that I hate my family. I hate my father. He’s just come back from Italy and those damned Fascists are in and out of the house at all hours. When I go down they’ll want me to stay in the country so I can run estate and he can do his bloody politics.” His hand shook. “I wish I could leave it all to poor Regs and hope that he won’t have a mind of his own.”

“What do you think you’ll do?”

“I don’t know—run away to the Continent—take a colonial post.”

“Surely it can’t be as bleak as that.”

“Is it bleak? It sounds rather wonderful to me.”

The amber June sunlight melted around them. It was hot, and Remus unbuttoned his collar. Suddenly he remembered the Polyommatus icarus, its cerulean wings throbbing in the clutches of Sirius’s fingers.

“Well, one thing you’ve got wrong. You’re not alone, Sirius.”

—

On the last day of term, after the balls and dinners and drinking parties had come and gone, Remus went up to Sirius’s rooms one more time.

“Are you in?”

“Yes, come in. Hi, Remus—I’m just packing.”

“I’ve just come to say goodbye. Are you going up to Wiltshire?”

“I wish you could save me, Remus. I can’t bear the thought of it—I’ll have to face them for an entire summer—God, I dread every minute of it.”

“Will you come down to London?”

“I’ll try—it’s all that I will try to do. Say, would you like to come up to Alington?”

“But are you sure they’ll have me?”

“Sod them, you’re my friend and I’m inviting you. I’ll write—I swear.”

“Yes,” Remus said, and took Sirius’s hand. They embraced. Remus bid his farewell and slowly made his way down the narrow stairwell steps.

II.

During the Long Vacation Remus went back to London and Sirius to the Blacks’ estate in Wiltshire. Remus reverted to the isolation of his sixth form, living in his father’s Clapham house. He began on his next Tripos exams on, knowing that he needed a double first for an MA; he spent much of his time reading at home when his father was out and at the Public Library when he was in.

The weeks passed uneventfully, at least by any outward account. Remus was reading the works of Russell and Hilbert, which he devoured like heretofore unformalised epiphanies. Daily he walked through the Poussinist ponds of Clapham Park, mulling over sections of Principia Mathematica, or the curved spaces of Riemann, or the concepts of Hilbert that seemed to fill his mind infinitely. And in the fading twilight he would amble home with more questions borne out of any answer he was able to glean. Daily he thought of Sirius. Yet daily he received no word, and hesitated to give word of his own.

Finally, on the last week of July there came a telegram from Sirius: FAMILY GONE WANT TO COME UP TOMORROW PLS REPLY BY TONIGHT. Remus read it at least three times before dashing off his reply: YES WILL COME UP ON 3 OCLOCK TRAIN, and packed his things.

The train was mostly empty. He sat uneasily, gazing out onto the rolling midsummer country, where the oxbowed rivers stitched together farms and hillocks. Remus was nervous to be among aristocracy, whose large and byzantine ways his upbringing did not prepare him for and in whose presence, he knew, he would be alone. Alington Manor, he had been told, was one of the last great country houses still in ancestral ownership, buoyed by a successive injection of American fortunes.

His car ride from Salisbury was stuffy though mercifully short. At the entrance he paid the driver ten shillings and collected his bag. The reports were not wrong; the house was indeed great.

Alington Manor sat atop a hill, sandwiched between two small rivers which marked the boundaries of its considerable grounds. It was a large Jacobean relic—which over the centuries fashion and comfort had made hybrid with modernity. The gardens had been redesigned in the 18th century in the French style, with formal parterres and a stately, linden-lined allée leading uphill. The house itself had the severe, rectilinear style of the Jacobean era. Much of its furnishings had been gutted and replaced throughout the ages, save the great entrance hall, where the original coffering and panels still gleamed, and set in the walls were the heraldic emblems of the family lineage, flanking the carven oak mantelpiece that bore the winged basilisk of the house of Black.

The butler greeted him at the door, “Mr Lupin.”

“Why, yes. That’s me.”

“Lord Alington has been expecting you. Presently he and Mr Potter are in the back garden. If you would just follow me—” Remus thought he caught a hint of disapproval in the man’s voice.

They found Sirius and James on the back lawn, already tipsy with wine. They were playing an atrocious game of croquet. “My dear Remus!” Sirius cried, and almost tripped on a hoop. “Thank God you are here. I was beginning to despair.”

“I caught a later train than I thought.”

“You didn’t eat on the train, have you?”

“No.”

“Oh excellent. We’ve had nothing except wine, waiting here for you. We’re starved.”

“Hullo, Remus,” James chimed in and embraced Remus rather unsteadily.

Drunk and laughing, they shepherded him into the small drawing room. “I assume you’d want a tour, Remus, but that can wait. Finally, they’ve all gone! We have all of it to ourselves.”

There were Madeleines and plover’s eggs on the side table. Sirius mixed more drinks, and they sat by the open bay window.

“To youth!” he raised his glass.

“To drink!” James echoed.

They ate their tea and soon resumed the game of croquet—playing now with increasingly absurd rules. Sirius insisted that they must switch sides every other turn, to which James added that each turn must also begin with a drink. When Remus jokingly objected that they might as well spin themselves beforehand, it was promptly added to the list of criteria. They could not manage more than thrice more each, and when Sirius, dizzy and stumbling about on his third turn, fell onto the ground, he took James with him.

“O Remus!” they cried. “Come down and join us—the grass is quite soft.”

Remus threw himself on them and they dissolved into a pile of laughter.

After dinner, Sirius had cocktails and lanterns brought outdoors while they tried to finish their croquet match. But it was nearly impossible to see in the dark. They made a lark of whacking the balls as far as they could, to decide in the morning the victor by the distance of their swings.

The next day they tallied up their scores.

“I dare say, Remus—you’ve got a hell of a swing,” James exclaimed.

Remus’s had made it all the way to the back fountain, and smashed into a garden pot. James’s was lying by the wayside, not ten feet from them. Sirius’s was found two days later in a rain gutter, quite mysteriously having travelled more distance vertically than horizontally.

“Well,” Sirius confessed with a smidgeon of regret. “I was always an awful shot at golf, too.”

They spent a week thus, habitually and happily drunk. One evening when they lazed about the patio, tired from a day of swimming and tennis, James said with a sudden soberness. “Sirius—I have to confess something.”

“What is it, old boy?”

“I can’t stay for long. In fact, I have to leave the day after tomorrow.”

“What?”

“Well, father is having a house party with people from his party. I’m to be introduced there and then I’m to follow him up to Scotland for a shoot. He’s been making quite the to-do about me. I simply can’t refuse, you see.”

“Oh.” Sirius seemed crestfallen. “But we all just got here.”

“There’s no helping it.”

“Well that rather ruins our plans—I had fancied we were going to travel! You might have told me earlier, you know.”

“I know. The telegram just came with the evening post.”

“My God, James. What a bore you’re being.”

“Well, do take pity on me—I shall be bored out of my skull.”

“A just punishment, I should say.”

—

True to his word, James left the next day, bidding goodbye to a sulky Sirius at the breakfast table while Remus made fun of his mood.

To cheer himself up, Sirius decided that they would ride out into a nearby wood. Remus was not a particularly keen rider, and had to be shown his way around the horse lest he spooked it. They rode out at an even walk, which was all Remus could manage, but Sirius would sprint away and return in spurts, citing the high spirits of his horse.

They followed the stream through the woods until they found the ruins of a medieval abbey. They hitched their horses, and sought shelter against the sun in the lee of an half-intact wall.

“I used to hide out here from my governess, Mrs Figg” Sirius said. “How she got in so much trouble when they found out she’d lost track of me. In fact, I think they sacked her.” He retrieved a bottle and a package of sandwiches from the saddlebags. “Sometimes I saw the farmers’ children. They were all afraid of me. That was before Regs was born—I then got a tutor who was quite strict about everything. He was truly insufferable; went on and on about the life of David Livingstone, who was his second cousin or something like that. When I gave him the slip he made me memorise a mountain of Matthew Arnold.” Sirius pursed his mouth in displeasure, as if remembering a sour taste.

“I hated Arnold,” Remus remarked absently. “The pomp of it—and the calculated melancholia.”

“He reminds me of the sound of Rimsky-Korsakov played on a wind-up pianola.”

Remus grinned. “A tinny pianola.”

“What bores we are, talking about awful poets in fine weather.”

“What else would we talk about?”

“Oh I don’t know—the trees, the flowers.”

“But I don’t know anything about trees or flowers.”

“Then tell me about the most beautiful equation you know.”

“The most beautiful equation?”

“Yes! I know perfectly well that you’ve already ranked all equations aesthetically.”

“Well, there is one equation.” Remus absently drew a circle on the ground. “It relates the rotation of a vector on a two-dimensional plane to the complex numbers. It says that there is a fundamental relationship between pi, which has to do with angle of a circle, e, the natural logarithm, and i, the imaginary axis of the complex plane. It encompasses analysis, geometry, and algebra in one simple relation.”

“But is it more beautiful to you than a poem?”

“Well, a poem is a single vantage point, tied to the ephemera. The Euler relation is like a truth sitting at the intersection of all vantages—eternal and unchanging.”

“Sometimes I feel that I’m almost convinced by you.”

Remus looked at Sirius, half-intent and half-drowsy. “Sirius, I have to tell you something—”

“What is it?”

“I—” he suddenly could not continue. “I—I think we should get going.”

But Sirius had taken his arm in a tight grip. The gauzy sunlight was on his face, and through the intervening years Remus could still remember its radiant, tender glow. How he had known. How Sirius’s brows slid apart, and the limpid spheres of his eyes scanned within their bas relief orbitals. They kissed under the corrugated shadows of the abbey, bluntly and without foreknowledge.

They regarded each other in the naked sunlight. They unhitched their horses and returned to those quiet and hidden woods, where low among the stalks of wildflowers they lied down and touched each other. The stream babbled nearby. Butterflies gathered and dissipated. The discourse of sun and horse and wood faded into distant lightning. Remus felt relief that love seemed to have found him after all, like an irreparable spell, a throb in the memory, beneath the watery loneliness to which he had thought himself exiled. And when he exhaled the words of love they seemed to fuel Sirius, seemed to burn in him—as if they were the alchemic flashes of a first storm falling after a long memoryless winter.

Remus often wondered what, if anything, they found beneath the cornerstones of that crumbling churchyard. In his memory, as often more than not, their twin figures trod into the dark anonymous woods and melted into the summer night. Diaphanous time could not follow them, no erosion or sunlight, and in phantom grottos they stayed, forever in love.

—

But time and world were ineluctable.

They soon found that the house was not their friend, for they were alone in it with the army of servants. Distance was painful. Sirius had Remus’s rooms moved to be near his and nightly they grew bolder. They picnicked alone in hidden corners of the garden, and sunned naked on the rooftops. Oh the mixture of youth and love, like an elixir. They dissipated its languid effects in the unwatched crevices of the house, where between the clicking feet of the hallboys they stole kisses and gropes, then more elaborate trysts in the hedge maze when the becapped shadows of the gardeners receded—or in the expansive incognito of the summer woods, where they spent the hot afternoons bathing in the stream and reading in the meadows, where under the curling midrib of a buckthorn leaf they found the jade chrysalis of a brimstone, and day after day Sirius walked to the same spot, wishing to witness the moment of translucent eclosure only to find the empty shell one morning, its owner having vanished into the smoky green air.

—

One day in mid-August a telegram was brought into the small drawing room where the two men were having lunch and an extensive course of wines.

The butler, Kreacher, a man whose sympathies clearly did not lie with Sirius and his associates, remarked rather unpleasantly that the family was unexpectedly returning home early from their vacation in the Riviera. Sirius looked at him sternly and replied, “Please, Kreacher, do not forget that I am also family.”

“Of course, my lord.”

“Oh Remus,” Sirius said. “What are we to do? They’re already at Dover. They say they’ll be here by dinner with enough time to change.”

“Can’t we meet them? It can’t be all that terrible.”

“You don’t understand. Of course it’ll be terrible. Maybe we could hire a car.”

“The chauffeur is out, sir.” Kreacher chimed in.

“Oh blast it. Thank you, Kreacher,” Sirius said by way of a dismissal. “If we stay, they’re bound to want to bother us—they’re always so damned curious.”

“What’s the harm? I’d like to meet your family—your brother, at any rate.”

Sirius looked at him, half-annoyed, half-resigned. “All right. We’ve got no choice.”

—

By teatime the family had arrived home. The servants lined up in reception at the entrance while Sirius watched from his third floor window, downing a shot of scotch. “They’re here,” he said drily.

“Won’t you go down to meet them?”

“Why should I, I’ll see them all the time.”

“Well, will you introduce me at least?”

Sirius had already downed another scotch and stood scowling by the curtains. “Oh, all right. If you must insist.”

By the time they came down to the great hall, Lord Hayneswick had already disappeared to his study with instructions not to be disturbed. Lady Hayneswick received them but cut their introductions short, excusing herself for being too tired from the return journey.

Regulus was eager enough to meet friends of his brothers. He was still a schoolboy, barely sixteen, comporting himself with something between temerity and aplomb and in confident possession of the hereditary good looks of the Blacks. He inquired after Remus’s studies—and after receiving what must have been a confounding answer, did not press on. Sirius treated him with half tenderness and half contempt.

“Did you meet any young person in Cannes?” he teased.

“Sirius, please!”

“That’s all I did when I was your age, you know.” Sirius glanced at Remus, trying to hide a grin.

“I’m sure that is nonsense.”

“Oh, how can you be so sure. The best summer I had you were laid up with a cough and couldn’t come. If I remember correctly it’s the Italians you have to watch for—they know their business.”

Regulus was blushing by now. “I’m going up to change, and I suggest you do the same.”

“I see you did meet someone—” Sirius called after him but there was no answer.

Sirius and Remus exchanged shrugs.

“Well, I guess he’s right. Let’s get dressed.”

—

Dinner was strained. Any bantering between the brothers had died at the first glance of their father in the drawing room. Remus tried his best to keep company.

“Mr—Lupin is it?”

“Yes, Lord Hayneswick.”

“That’s a rather uncommon name.”

“Yes, I suppose it is. My family is—Sephardic. We’ve been in England since the 1800s and anglicized the family name.”

“Ah, I see. But you have converted to the faith.”

“Well—yes and no. My mother did not, though my father did after her death. As for me, I grew up with neither religion and now I don’t really see the need.”

“Oh, yes, of course. Quite true.”

Sirius barely touched his plate, toying with his vegetables. He looked up now and then to glare at his father, who seemed to barely register his presence.

Regulus tried to save the conversation, describing their stay at Cannes and the various companies they received there, but everything had soured and they ate in a moody silence.

—

After dinner, Remus went to fetch Sirius, who had been called to the library by his father. As he reached the door he could hear their raised voices through its walls.

“How dare you bring one of them in to my house.”

“He is my friend—one of my dearest—”

“Oh, that’s it, is it? Why don’t you go and befriend any manner of unsuitables and invite them for dinner—a Jew! At my table! And don’t think I haven’t heard about your carrying on at Trinity…deplorable… do you understand how that will reflect on me? I’m the laughing stock at the club… You must think before you attach yourself to people…”

Remus shut the door quietly.

He had retreated half way up the stairs when Sirius caught him.

“Remus.”

“Oh, hello there.”

“I hope you didn’t hear that.” He looked pained.

“I’m afraid I rather did.”

“Oh. How ghastly for you. I’m sorry, my father’s being an absolute beast.”

“Is he?”

“Oh Remus, I knew we should have taken off last night as soon as I’d heard. Let’s leave now. We can take the first morning train. I’ll say goodbye to Regs tonight.”

—

They packed bags and left early in the morning. In London they ate breakfast and decided to go to Cornwall by train, where Remus’s father had a cottage in Penzance.

“What d’you think they’ll think—finding us gone?” Sirius said.

“I don’t know. They’re your family.”

“Well. They don’t feel like my family. I don’t know what devil gave them to me, or vice versa.”

“Devil or not, there they are.”

“They must have been beastly for you.”

“They were perfectly civil to me.”

“Precisely—that’s the awful thing about them, that they manage to be such civil, bloody beasts.”

Hills rolled by, and then mountains, and at last they cleared the coastline. Sand and shrub dotted the moors, and the unceasing wind blustered against their window and rowed the trees back.

Remus remarked, “It’s strange to think we’re still in England.”

“Not quite, I should think. We’re in Cornwall—hell of a difference.”

They found the cottage abutting a low bluff, overlooking a field of marshy bitterned reeds and a strip of the bay. Church bells rang out in the distance, though it was a Friday.

“It’s Assumption Day,” Sirius explained. “I’m surprised we were able to hire a car at church hours, though they’re all Methodists down here, I gather.”

The salt sea air, already balmy with heat, cleaved to them. Remus turned the door key.

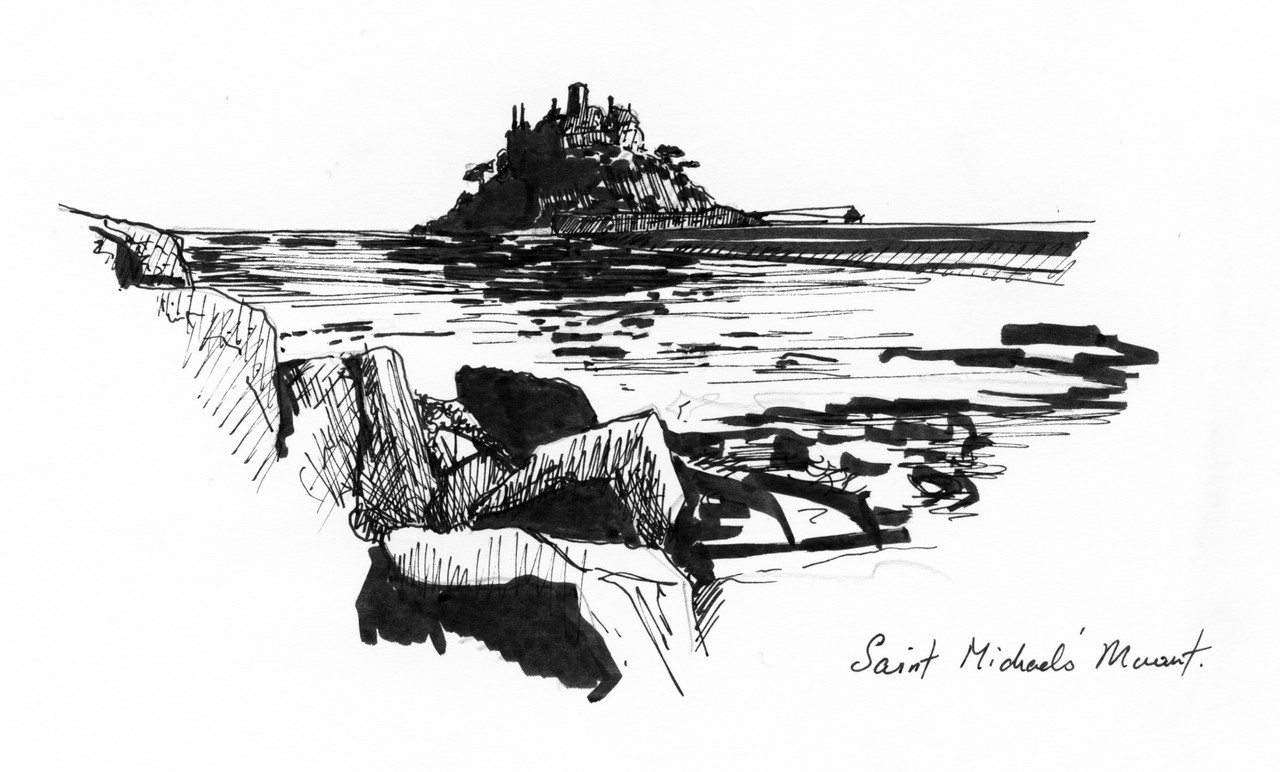

It was a small house, built in a row of rusticate summer cottages when the railway first opened. It had not been maintained well; dust flecked in the sunlight and danced on the furniture coverings. The yellow damask wallpaper was fading near the window. Through the drawn curtains they could see the town below—two summer rooks perching on a steeple and Saint Michael’s Mount floating ahead, a smudge of bruised umber against the copper blue of the bay.

“It’s wonderful,” Sirius proclaimed and flopped onto the sofa by the fireplace.

“It’s not quite what you’re used to.”

“Oh, nonsense. I’m not used to anything.”

They regarded each other. Remus extended his hand. Sirius pulled him down.

—

Remus woke to the clop and toss of cart mules driven to town for the morning market. Remus found Sirius down stairs lying on the sofa in the sitting room, drinking tea.

“I’m surprised you know how to make tea.”

“Good morning to you too.”

Remus bent down to kiss him.

“I know how to boil water at least, if that’s what you mean.”

He hadn’t shaven, and Remus felt the prickle of his beard against his palms. Sirius looked up at him, his symmetric features strangely transposed by his posture. He set down the copy of Ulysses he had been reading.

“Is it a good read?”

“Hardly. It gives me anxiety—I can’t tell if I love or hate it.”

“That doesn’t sound particularly good.”

“Well, I had quite an ordeal smuggling it in—I butchered a dictionary to disguise it. Good thing the customs man was a total brute—could not make heads and tails of any book.”

“What’s it about?”

“Oh, a man’s thoughts, I should think. Mr Leopold Bloom.” Sirius regarded him with a strange expression. “He goes about Dublin, buying soap and going to a funeral.”

“How can they make a whole book out of that?”

“Apparently they can make a frightfully interesting book. It’s about his mind, you see. You should read it.”

“I wonder why they banned it.”

“Well, you know how it works. There is no rationality behind it. This day it’s undergarments and another day it’s the Fenians. The Ministry of Information, from what I gather, would rather we could get rid of the Irish, all foreigners, women, and procreation. And then lobotomise everyone that’s left lest they become too anxious about it.”

Remus smirked. The thought was gruesomely fitting. “Let’s go find some breakfast in town, I’m famished.” He took some of Sirius’ tea. “Especially if this is your idea of teacraft.”

“I said that I could boil water, but I never said I could make tea.”

“Shall we go to the beach today?”

Sirius made a face. “I dare say not. It’s so—bourgeois.”

“I didn’t know you were such a snob,” Remus wrestled Sirius out of the sofa, half-tussling and half-tickling. “Go get your things.”

The day was very late when they got down to the beach. They found a footpath that arced along a high bluff and ended in some stairs of sorts, hewn into the living stone. The sun hovered a length above the horizon, outlining the shadow of Saint Michael’s Mount.

“Listen,” Sirius said. “It’s the sea.” From the bluff they could hear the cool rocky waves, the faint music of distant storms. The sea crashed on the jagged rocks, salty and rich. “Thalatta! Thalatta! they cried when they saw it.”

“Who did?”

“The Greeks, when they returned from Persia, scattered and defeated.”

“What does it mean?”

“Simple. ‘The sea, the sea.’”

“Oh.”

“There is something in the words—something profound. Something about the repetition, the prosody. I could write pages on them—just two words.”

“I’ve read mountains of papers written on the nature of nothingness.”

“Oh but you miss the point—it’s not the brevity. No. It’s the breadth of it. Those two little words.”

They clambered down the rocks onto the shore. A light came on atop the castle on the island, flashing in the settling darkness. The beach was marshy and trackless. The land felt impossible to Remus. It was too barbed and wild, too hard, waking the names of Arthur and Merlin, of giants and spirits. He felt strangely unfettered.

They rooted about the dark for the land bridge to the island.

“I think we’ve gone past it. It’s too dark to judge,” Sirius said.

“Maybe we should turn back.”

“No, I dare say not—we’ve walked all this way.”

When they finally found the rock-strewn head of the causeway they found the setts buried in water—of course, they were too late. The tide had come in.

They sat down on the rocks and watched the sun go down. Sirius said after a long silence, “When I was a child I used to fear that in the dark—or when I closed my eyes—all the things about the house were moving; that there was a subtle deceit in everything, hidden by the light. Children are perfect solipsists, aren’t they?”

“It’s funny you should say that—I think I treated people the same way, but quite the converse. I used to think that they became animated solely at my discretion, and they were like puzzles to me. I used to try to make my father cross just to see how predictable it all was. Maybe that’s what we are—predictable machines.”

“What an awful thought.”

“Why do you say that?”

“You don’t think that’s awful?”

“No I don’t. Sometimes I think it’s wonderful—if we were all just sufficiently complex equations, waiting to be solved.”

“Oh Remus, do you not believe in a soul?”

“No. I don’t.”

“Not even in the profane sense, without any of the religion?“

“No.”

“But don’t you believe there must be something inside the chaos—some hidden heart? Isn’t that the soul?”

“Maybe. And maybe the soul is a solvable organ, living inside the brain. What is the soul, Sirius?”

The thought seemed to distress Sirius; his face flashed and faded in the twilight, and his voice seemed to fill the dark void between them. “I don’t know,” he said, almost in a whisper. “But I hope you’re wrong. I hope the soul is neither inside nor outside of you.” Sirius took Remus’ hand and gripped it tightly. The sun had slipped beneath the waters, leaving behind just purplish streaks in the sky. Evening colours fell onto the water like the blurry shadows of a high battlement.

“And I hope that the world is sand and light. And the sea. Always the sea.”

—

Remus would remember those nights in Cornwall when they shared their bodies without reservation; with the poor tools of their clumsy limbs they tried to reconstruct the cosmos and all its constellations of spacious darkness and luminous stars. The velvet yellow moon, obscured by cloud or memory, waited for them in the shy curve of its instep, above the exhaling window box flowers.

For a month they stayed in Cornwall. They thought of telegramming James or Pettigrew, but decided against it in the end. They spent their days revelling in each other’s company, in the reedy marshes and the hewn rocks, hidden in a fold of time. They trekked out to distant cliffs. They found caves where beside the shallow tidal pools they lay together in the sand. London and Alington and Cambridge were forgotten; their friends retreated into distant shadows. Remus did not fall in love, could not feel in it the etherish pull of gravitation—but rather love had coalesced in him, a radiant substance in whose swirling chaos he found the bright, crystalline centre.

It was not Sirius’s beauty that Remus would later remember, but the individual details of his person, filtered through the kaleidoscope of memory, gaining in infinite tenderness what they had lost in shape and colour. Like an anatomist he would remember the mouth and hands, to varying degrees soft or angular, the curl of his hair above his ear like a small creature’s, his poised eyes, and the dark shadows of his throat grading into its pale apex, the way his shoulders gathered in the light, the smell of salt and the smell of Sirius, the beach, the endless summer, the sufficient magic of the sea. Remus remembered it all, though the whole Sirius—the lively whole—he could never rescue from the crumbling sepia.

But if happiness could live on, then opalised happiness he would scatter on the strand, his indelible happiness buried under the muddy Cornish water, under the summer sky, under an unknowing universe where wheeling in the abyss of oblivion his happiness would still be, harder than matter and lighter than air.

—

They parted at the end of September, simply and without fanfare, for they had thought their separation would be a brief week of hiatus before an inevitable reunion. Sirius went back to make amends with his family and Remus went up to Cambridge early. He had contacted Welchman, a mathematics fellow working on probability theory, eager to begin his work.

He spent a week reworking for himself the fundamental properties of probability; its structures and interactions. He tried to think little of Sirius, who was due to return in a matter of days.

But disaster—which had loomed always in the horizon—soon struck.

On the morning before start of term his bedder brought in a telegram. It was by Sirius from London: PLEASE PHONE URGENT. He grabbed his coat and ran out down to the porter’s lodge where there was a telephone.

“Oh Remus, Kreacher’s ratted me out to father.” Sirius’s voice crackled in the receiver.

“What? But how?”

“One of the maids must have seen us together. Oh God, Remus—now they all know. Damn them all.”

“But he’s got no proof—”

“No, he doesn’t need proof—just the opposite. He won’t dare let anything survive that the papers might catch whiff of. God knows what he’s doing to shut the poor girl up.”

“But Sirius, what are they going to do?”

“They’re sending me to a doctor in Switzerland. I think they’ll say I’ve gone traveling.”

“And what will you do?”

His voice sounded small. “I’m going.”

“Why won’t you refuse?”

“Oh Remus. I can’t.”

It didn’t make any sense. “But no body will care! There’s an absolute Bacchanalia in Leicester Square every single night. The papers don’t bat an eye—all they report is what everyone was wearing.”

“Remus, you don’t understand. The papers will care if father cares.”

Remus gripped the receiver. “Won’t you at least come by Cambridge? To say good-bye?” he pleaded.

“I’m sorry, Remus.” Sirius’s voice seized on the last words. “I can’t see you anymore.”

“This is it, then.”

“I suppose so.”

“Good-bye. Sirius.”

“Good-bye.”

And then the line was silent.

Remus hung up the receiver. He stepped out. It was raining outside—a sort of quiet, dreary rain. The air smelled of cold minerals and the rotting autumn leaves tangled in the street gutters. He walked out into the front courtyard, past Gibbs’ building, past the Fountain, and stopped at the Chapel. He stood dumbfounded. Rain blurred his vision and fell from his face. It seemed to Remus, that in the bright and dark glasspanes of Chapel, diversely opaque or viridian or dipped in vermillion, he saw the lives of men in their allotted, monstrous motions—here the blind march of the pawn, here the still and circumscribed king, here the crooked L of the knight.

And in the weeks, months, years after, conflicting reports cropped up, among the society papers and dinner parties, tales of half a dozen gallivanting Siriuses dispersing throughout the Continent and beyond, in polar opposite directions—that Sirius took up with an opera singer in Venice, that he was touring Africa with a man of the Blacks’, that he had sailed for Australia, that he was in Long Island, that he eloped with a Miss Banks to Hong Kong, that Sirius was dead.

—

Sirius was not dead, this much he knew. He knew this with an almost supernatural conviction, as if there was some broadcast station in the heart that love had instructed; that between them was a secret code, a hidden frequency that could penetrate all known matter—and if one was dead the other would know, deep down, a supreme entanglement that would travel faster than light.

It was not until later, when the war had taught him the worst in people, that Remus realised why Sirius never resisted: that Lord Hayneswick must have threatened not only Sirius, but himself. And through the years he tried in vain to find him. Among the gossip columns and foreign reports he searched for news of one lost English lord, while the Black family fortune rose and imploded around him. They were prominent in politics: Lord Hayneswick had joined up with the British Union of Fascists and often railed publicly against the “great Communist and Semitic threat to Britain.” Bellatrix Black, daughter of Lord Hayneswick’s younger brother, had married a high-ranking German officer. Her sister Narcissa married Oswald Mosley, the Fascist party leader.

Regulus Black went up to Trinity in 1936, though by that time Remus had already traded the cloister of Cambridge for the grey Georgian houses of London, the willow-meads for overflowing streets.

By the beginning of the War, the Black family was almost entirely ruined. The Fascism movement had failed; appeasement had failed. The Earl of Hayneswick had retired from Parliament in disgrace and shortly after died of a heart attack. There was no more money in the family to pay either the increased death duties or the new wartime tax; Alington Manor was sold for a pittance and became a military training base.

Still, there was no mention of Sirius.

When Remus was recruited to Bletchley Park, it was on one condition: That if any man by the name of Sirius were found in the officers list, he would be informed. His superiors reluctantly agreed, after much hemming and hawing about his motivations, but in the end nothing came. He had hoped, through the dark years of the war, even to find it among the list of the war dead. When ceasefire broadcasted to a weary and joyed nation, he secretly mourned.

He had closed his heart. He told himself that he would think no more of Sirius Black.

—

After the War he moved to the United States. He had gotten a job at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, teaching a course on the theory of computing, conducting research on the mathematics of cryptography. He had rented a small house in Cambridge, MA, on a hill near the cemetery overlooking the bend in the river.

And then, it was another spring.

It had been a fine though undistinguished morning when April had come again. He had made coffee and toast and came out for the morning mail. Buried in the magazines and grocery adverts he found a peculiar but modest envelope, addressed from a London hotel he’d never heard of before. But inside, he immediately recognised the hand:

My dear Remus,

I hope to God that this is you. My heart trembles at the thought that this will go astray—ending up in some ill-meaning bureaucrat’s hands—or worse, nowhere at all.

I sought for you in vain in Cambridge. I asked around and got this address from Slughorn, your old dean at King’s. He’s retired now. I hardly recognise anyone, which is neither surprising nor unfortunate. I went back to see Regs. He showed me the old family land—there’s nothing left of Alington, nothing. They’ve carted off every stone. I managed one last ride to the abbey ruins, which still stands at the bottom of the valley. Oh Remus, I’m sorry. There’s so much that I want to tell you, but prudence forbids me from putting them into words.

I can only hope that I’m not being narcissistic when I suppose you must be curious where I had been all these years. Remember that they sent me to Switzerland? I pinched some money and gave them the slip in Zurich. I made it all the way to Hong Kong before the money ran out, and I had to manage on my own. I met a Trinity man there—two years our senior—who found me a post at an American bank. I thought I would spend a few years there and then move on. But then there was the war. When the Japanese came they rounded up all the Europeans and Americans.

We had absolutely no news in the camps, no idea what went on outside. Imagine my surprise at finding myself in Cambridge again—Cambridge, five years later! Never had the sight of those cupolas and steeples been happier to me. But I cannot find anything or anyone. I have no idea what happened to you.

In the palace at Potsdam where Frederick the Great once summered there is a certain Caravaggio. It is a painting of Saint Thomas, bending over the umber backdrop, his finger protruding into the wound of Christ. Oh Remus. How each history is in our body; how it shakes out of us in the night. That body is your body, that finger is your finger, and each limb of you is pierced.

Do you remember what you said to me, that day when we tried to get to St Michael’s Mount but found the bridge overrun by the tide? I believe you now. There are no angels. There is no soul. Only this.

Please write back to this address, even if to say that we can no longer meet; even if you destroy this letter.

Yours,

S.

The newspaper boy cycled by and chimed his little bike bell. A motorcar followed him. Sunlight flecked through the broad palmate chestnut leaves, almost cruel in its purity. What more colour could his poor mind lend to it, to any of it?

Remus stood very still. His heart trembled in its cage. His fingers moved along those words, gingerly, profanely, as if he could lift them from the paper and navigate among their intimate, invisible streets—to taste and love the hand, the arm, the shoulder of their creator—to touch his eyes, his mind, his heart.

He looked down his suburban lane, its chestnut-lined avenues, its colonial houses, its narrow path leading up to the river. The scent of spring rose up in the air. Above him was the sun. The sky. The universe. And inside him—joy like all human weather.

finis.